A case study and management tips on this severe and potentially life-threatening condition.

Primary adrenal insufficiency, also known as Addison’s disease, is a rare, but severe and potentially life-threatening condition occurring from a deficiency of adreno-cortical hormones.

It was first described in 1855 by Thomas Addison in Guy’s Hospital in London and from whom the name of the disease is derived. From then, it took almost a century for synthetic corticosteroids to become available to treat the disease, which until then was almost universally fatal.

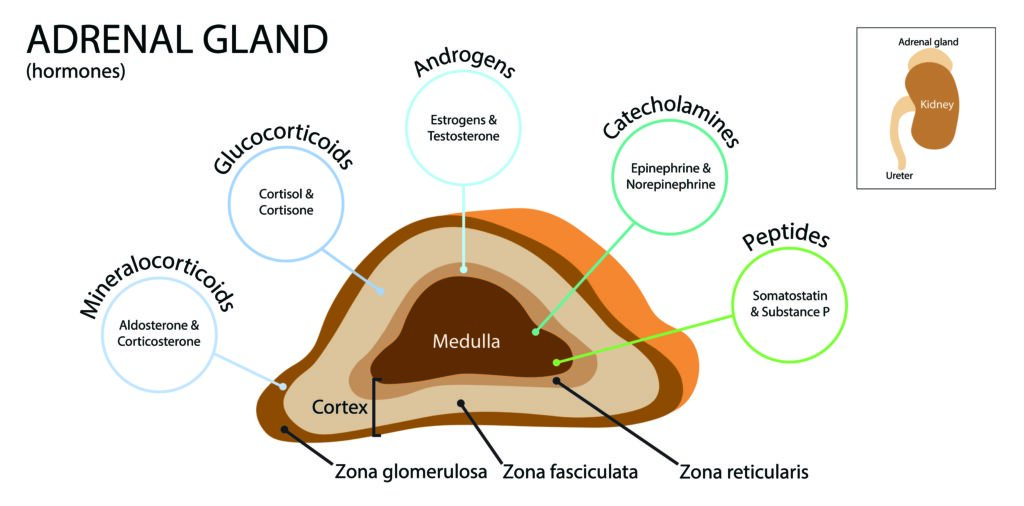

The adrenal cortex produces glucocorticoids (cortisol), mineralocorticoids (aldosterone) and androgens, under the influence of pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation for glucocorticoids, and the renin-angiotensin system regulates mineralocorticoid secretion (Figure 1). Thus, primary adrenal insufficiency is characterised by deficiency of cortisol, aldosterone and adrenal androgens, with a secondary or reactive rise in plasma levels of ACTH and plasma renin activity.

Once the diagnosis has been confirmed, primary adrenal insufficiency requires lifelong replacement therapy with glucocorticoid (hydrocortisone) and mineralocorticoid (fludrocortisone – a synthetic substitute for aldosterone).

The incidence of primary adrenal insufficiency is 4–6 cases per million per year and seems to be increasing. Prevalence estimates are around 100 cases per million of the population, indicating 2500 affected patients in Australia.

Autoimmune adrenalitis is the most common cause and may occur alone or as a major component of autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes Type 1 and Type 2.

Less common causes of primary adrenal insufficiency include congenital adrenal hyperplasia, adrenal haemorrhage, infection (chiefly tuberculosis), metastatic cancer and some rare genetic diseases. Women are more commonly affected than men and it may present at any age.

Secondary adrenal insufficiency is more common than primary adrenal insufficiency and results from insufficient production of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) by the pituitary gland secondary to pituitary disease or suppression of secretion from use of long-term synthetic corticosteroids administered for management of medical disorders requiring anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive therapy. It may also develop in patients during long-term treatment with opiates.

Clinical presentation

The presentation of primary adrenal insufficiency from Addison’s disease depends on the rate and extent of impairment of adrenal function.

It usually manifests insidiously with a gradual onset of non-specific symptoms, often resulting in a delayed diagnosis. The symptoms may worsen over time, making early recognition difficult. A correct diagnosis is delayed by one year or more in approximately 50% of patients with primary adrenal insufficiency.

In many cases, the diagnosis is made only after the patient presents with an acute adrenal crisis manifested by life-threatening hypotension, hyponatremia, hyperkalaemia and hypoglycaemia. This may occur spontaneously or be precipitated by a stressful illness such as infection, trauma, surgery, vomiting or diarrhoea.

Patients with Addison’s disease typically report overwhelming exhaustion, fatigue, generalised weakness, weight loss, poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal symptoms, joint or back pain, dizziness on standing and muscle weakness. Salt cravings and an increase in thirst and urination are common. Anxiety, minor depression, irritability and inability to concentrate may accompany chronic exhaustion.

Adrenal Fatigue – does it exist?

The term “adrenal fatigue” has become a popular diagnosis and has been used to explain a group of symptoms that are said to occur in people who are under long-term mental, emotional or physical stress. Symptoms said to be due to adrenal fatigue are mostly non-specific and to our knowledge there is no scientific evidence to support this diagnosis. Consequently, patients labelled with this diagnosis are erroneously prescribed corticosteroid therapy and with time may end up suffering from suppression of ACTH and true secondary adrenal insufficiency. In our experience, normal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function returns with appropriate long-term management.

Clinical signs and disease progression

The most characteristic clinical sign of primary adrenal insufficiency that occurs in almost all patients is hyperpigmentation. It is usually generalised and most prominent in pressure areas, over palmar creases, elbows, knuckles, posterior neck, areola of the nipples and the scrotum in men.

Pigmentation of mucosae is diagnostic of primary adrenal insufficiency (small brownish patches on the lips, the gingival mucosa, the palate and the tongue). Elevated ACTH and melanocyte-stimulating hormone are causative factors. Hyperpigmentation is not seen in secondary adrenal insufficiency because ACTH and MSH levels are low.

As the disease progresses, other signs that become apparent include dehydration, tachycardia, postural hypotension and proximal myopathy or global muscle weakness.

Reduction in the amount of axillary and pubic hair may occur in females from loss of adrenal androgen secretion. Clinical signs of other associated autoimmune diseases (e.g. thyroid diseases, vitiligo or others) may also be present.

Diagnosis

Laboratory testing reveals hyponatraemia, often accompanied by hyperkalaemia and less frequently hypoglycaemia.

Plasma cortisol, on blood best taken at around 0900 hours, is subnormal (reference range 138-650nmol/l) and is accompanied by an elevated plasma ACTH level. A morning cortisol level of less than 100nmol/l, with an elevated ACTH, is invariably consistent with the diagnosis of primary adrenal insufficiency. However, most cases require a short Synacthen test (synthetic ACTH stimulation test of adrenal function) to establish a definitive diagnosis.

The most recent American Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for managing primary adrenal insufficiency make the following strong statement:

“We recommend diagnostic tests for the exclusion of primary adrenal insufficiency in all patients with indicative clinical symptoms or signs. We suggest a low diagnostic (and therapeutic) threshold in acutely ill patients, as well as in patients with predisposing factors. This is also recommended for pregnant women with unexplained persistent nausea, fatigue and hypotension. We recommend a short corticotropin stimulation test (Synacthen 250?g) as the “gold standard” diagnostic tool to establish the diagnosis. If a short corticotropin test is not possible in the first instance, we recommend an initial screening procedure comprising the measurement of morning plasma ACTH and cortisol levels. Diagnosis of the underlying cause should include a validated assay of autoantibodies against 21-hydroxylase. In autoantibody-negative individuals, other causes should be sought.”

The short Synacthen test can be performed at any time of the day by drawing blood for serum cortisol at baseline and 30 and 60 minutes after parenteral administration of 250g of synthetic ACTH (Synacthen). The cortisol response to ACTH is higher at 60 minutes than at 30 minutes. The exact diagnostic cut-off for diagnosis depends on assay-specific local reference ranges and is usually set at 500-550nmol/L for a normal response to ACTH stimulation.

Unfortunately, diagnosis is often delayed and formulated only in the presence of an adrenal crisis.

If left untreated, an adrenal crisis is invariably fatal with rapid evolution to coma and death (within 24 to 48 hours).

Wherever there is a real suspicion of adrenal insufficiency, the patient should promptly be referred to a specialist endocrine unit for a short Synacthen test and if hypotensive and vomiting, or where the 9am cortisol is less than 100nmol/L, an immediate referral should be arranged.

Clinical case study

Mrs JH, a 76-year-old woman, presented to her GP early in June with a two-month history of dizziness,intermittent nausea, dry retching, loss of appetite and periumbilical pain associated with a weight loss of 7kg. She had a history of hypothyroidism due to autoimmune thyroiditis, treated with levothyroxine 100ug daily,

A diagnosis of blastocytosis was made from stool cultures and metronidazole was prescribed. Still feeling very unwell the next day, she presented to the Emergency Department of her local hospital. Again, no specific diagnosis was made but hyponatraemia (sodium 129mmol/l) was noted. CT scan of the abdomen was unremarkable (no abnormalities were noted in the adrenal glands), and she was referred to a gastroenterologist for consultation.

She was booked for endoscopy six weeks later (27 July) that showed a small hiatus hernia and Helicobacter pylori on biopsy. During that admission, the gastroenterologist noted her hyperpigmentation and vitiligo, and coupled with hypotension (systolic blood pressure ranged from 86 to 106 and diastolic from 51 to 76 mmHg), she suspected a diagnosis of Addison’s disease.

Laboratory tests on blood collected at 1500 hours revealed a borderline-low plasma cortisol level of 194nmol/l and grossly elevated ACTH level of 558pmol/l (RR <12pmol/l), highly suggestive but not diagnostic of Addison’s disease. These tests were repeated on two occasions over the next week with contradictory and equivocal results delaying a definitive diagnosis. Plasma aldosterone was subnormal at 60pmol/l (RR 100-950) in the presence of hyponatraemia and an elevated plasma-renin-activity consistent with mineralocorticoid deficiency. Adrenal cortex antibodies were negative. A Synacthen stimulation test was arranged for a week later on 6 August but was not performed because of difficulties in undertaking this during the covid crisis.

As she had increasing dizziness and worsening lethargy and orthostatic hypotension, with BP of 116/82 (sitting) and 99/69 (upright position) and there was concern of an incipient adrenal crisis, replacement therapy was commenced the following day, 7 August, with hydrocortisone 14mg mane and 4mg midi, and fludrocortisone 0.1mg daily. Her current health status is satisfactory, with appropriate corticosteroid replacement therapy for primary adrenal insufficiency

Commentary on the case study

This lady typifies the difficulties and delays in making a definitive diagnosis of Addison’s disease.

Symptoms and signs, while incapacitating, are often non-specific and they escaped the notice of her usual medical attendant and those she consulted in the emergency department. A high index of suspicion in a patient with hyperpigmentation, hypotension and hyponatraemia, as in Mrs JH’s case, could have led to an earlier diagnosis. The delay in confirming a definitive diagnosis of Addison’s disease by a Synacthen stimulation test put the patient at increased risk of an adrenal crisis. The assay used by the laboratory did not measure specific 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies (21OHAb), markers of an adrenal autoimmune process that identifies individuals with autoimmune Addison’s disease.

The clinical presentation and associated autoimmune disorders of vitiligo and autoimmune hypothyroidism are highly suggestive of underlying autoimmune adrenalitis as the cause of her primary adrenal insufficiency. As 21OH-autoantibodies are reliable and robust markers for autoimmune Addison’s disease, we are planning to organise a 21OH-Abs assay [SS1] in a different laboratory.

Adrenal crisis

An adrenal crisis, also called an Addisonian crisis or acute adrenal insufficiency, is a life-threatening medical emergency that is frequently the initial presentation of primary adrenal insufficiency.

Most patients with this condition will suffer one or more episodes of adrenal crisis during their lives. In a recent review in the New England Journal of Medicine, Rushworth and colleagues stated that up to 8% of primary adrenal insufficiency patients will probably suffer an adrenal crisis annually.

While there is no clearcut definition for an adrenal crisis, it is what occurs in a patient with Addison’s disease whenever there is an acute deterioration in well-being, accompanied by dehydration, hypotension and electrolyte imbalance (hyponatraemia and hyperkalaemia). Some authorities use the term “incipient adrenal crisis” to describe the disturbed clinical state preceding a full-blown adrenal crisis.

In this situation, treatment with parenteral hydrocortisone and intravenous fluids is indicated to avert an adrenal crisis. Patients and close relatives should be educated about the symptoms and signs leading up to the development of an adrenal crisis and instructed in the use of self-administration of parenteral hydrocortisone to prevent it.

Intervention with parenteral hydrocortisone therapy is indicated whenever there is a suspected adrenal crisis. Delayed intervention can lead to death.

Hydrocortisone should be administered parenterally in a dose of 100mg and urgent attendance at a hospital emergency department is required for administration of intravenous fluids for resuscitation, supported by hydrocortisone 50mg intravenously every 4-6 hours. Lower doses are indicated in children. It must be emphasised that poor outcomes result from poor decision-making, delayed intervention and inadequate replacement therapy.

Associated autoimmune disorders

Addison’s is often associated with other autoimmune conditions including hypothyroidism (range 43-44%), vitiligo (9-10%), vitamin B12 deficiency (7-9%), type 1 diabetes (5-6%), premature ovarian failure (5-12%), coeliac disease (3-6%) and hyperthyroidism (4-5%).

Adrenal failure may be the first autoimmune condition to manifest, with pre-existing associated conditions more likely in women.

Annual clinical assessment and appropriate hormonal and autoantibody screening, particularly for hypothyroidism, should be undertaken at regular intervals as most of these associated disorders are frequently overlooked because of their insidious onset.

Treatment

Glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement therapy

- Hydrocortisone in a daily dose of 15-25mg is the recommended glucocorticoid replacement therapy, given as two-thirds of the total dose on awakening and the remainder later in the day, usually by early or mid-afternoon. Alternatively, cortisone acetate can be substituted in a dose of 20-35mg per day; again, given twice daily in divided dosage as recommended for hydrocortisone. Mineralocorticoid replacement is recommended with fludrocortisone 100ug to 200ug once daily. This suggested dosage regimen is only a guide and must be adjusted to provide optimal care for the individual. For example, some patients do better by splitting therapy into three or even four daily increments. Replacement with synthetic glucocorticoids, such as prednisone or dexamethasone, is not recommended. Lower dosages of hydrocortisone should be used in children, who should be managed by an experienced paediatric endocrinologist. Management of pregnancy in a woman with Addison’s disease usually requires increased dosage of medication, particularly in the third trimester, and care is best provided in a multidisciplinary clinic.

- Monitoring of glucocorticoid replacement is best done by a general clinical assessment of well-being, to ensure early detection of deficient or excess dosage, coupled with measurement of body weight, blood pressure (particularly by excluding orthostatic hypotension and/or oedema) and a check of serum electrolytes. Routine monitoring of plasma ACTH is generally not recommended, but not all clinicians agree with this view.

- Monitoring of mineralocorticoid replacement is best performed by ensuring blood pressure is kept within normal limits while preventing postural hypotension, coupled with regular checks of serum electrolytes and measurement of plasma renin activity.

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) replacement therapy

- DHEA replacement therapy for women with Addison’s disease remains controversial. Current guidelines recommend a six-month therapeutic trial of DHEA in women who are otherwise well-replaced but may be suffering from lack of libido and have low energy levels. The usual dosage is 50mg twice daily.

Patient education

- The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responds to any stressful situation – be it psychological or physical stress – by increasing adrenal cortisol production. The degree of response is dependent on the nature, severity and duration of the stressful event, and is characterised by a large degree of variable responses among patients. Thus, there is no simple way of defining the level of stress and quantifying the physiological response. There isn’t any data available from randomised trials to guide adjustment of therapy. Therefore, patients with primary adrenal insufficiency must learn through experience, but education and knowledge of how to respond is a prerequisite for a satisfactory outcome and should be made available to all.

- Every patient with primary adrenal insufficiency should carry some form of identification that readily identifies them as suffering from Addison’s disease and provides a link to their medical history and the details of their corticosteroid replacement therapy.

- Patients should be equipped with written information on how to adjust hydrocortisone dosage at times of stress or intercurrent illness, a so-called “sick days regimen”. The usual advice is to double or triple the daily hydrocortisone dosage until the illness abates and seek advice from the usual medical attendant. In the event of vomiting or being unable to take the medication orally, the patient and/or a trained relative or friend should administer hydrocortisone (Solu-Cortef) 100mg intramuscularly or subcutaneously and seek medical attention.

- Hydrocortisone cover for surgery: for major surgery with general anaesthesia, severe trauma, delivery should be provided with hydrocortisone 100mg given intravenously followed by a continuous infusion of 50mg every six hours.

Key messages

- Primary adrenal insufficiency, or Addison’s disease, is a rare, potentially lethal but treatable disease.

- The symptoms and signs of onset of primary adrenal insufficiency are usually insidious and non-specific, leading to delays in diagnosis with a high risk of culmination in an adrenal crisis and possible death. Unexplained hyperpigmentation, fatigue, weight loss and hypotension should always raise the possibility of underlying primary adrenal insufficiency.

- If an acute adrenal crisis is clinically suspected, hydrocortisone should be administered without delay (100mg bolus injection). If possible, blood samples for paired serum cortisol and ACTH should be drawn beforehand. The patient should then be hospitalised and administered hydrocortisone 200mg per 24 hours, either as a continuous infusion or 50mg every six hours along with intravenous fluid, 0.9% normal saline, for resuscitation. In haemodynamically stable patients, a short Synacthen test can be performed; however, if in doubt, it is better to treat promptly and confirm the diagnosis later after the patient has recovered from the crisis.

- Standard adrenal hormone replacement therapy consists of multiple daily doses of hydrocortisone (15-25mg in total) or cortisone acetate (20-35mg in total) and fludrocortisone 0.1mg to 0.2mg daily.

- Patient education is essential to empower the person to adjust daily dosages of medication to deal with intercurrent illness (sick days regimen) and to administer parenteral hydrocortisone. The patient should carry a means of identification such as a bracelet (Medic Alert) and written information about their illness in case of emergency.

- Annual follow-up is recommended by an endocrinologist to monitor and optimise replacement therapy and to confirm or exclude the development of other autoimmune disorders.

References: supplied on request

Creswell Eastman AO is a Clinical Professor of Medicine the University of Sydney and a Consultant Emeritus Westmead Hospital Sydney.

Kamala Guttikonda is a Consultant Endocrinologist in Mona Vale and Gosford, VMO in Northern Beaches Hospital and Visiting Endocrinologist NSW Rural Doctors Network.