Most cases of bronchiolitis can be managed in primary care, but recognition of severity is critical.

Why is it important for GPs to know about bronchiolitis?

Bronchiolitis is the major respiratory illness in infants (less than 12 months of age) and the most common cause of hospitalisations in this age group.

Although most cases are mild4 and can be managed in primary care, most hospitalisations are in infants without recognised risk factors for severe disease (see below). Infection with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), the most common cause of bronchiolitis in infants, does not confer protective immunity, so repeat infections are common. A significant proportion of infants with RSV bronchiolitis go on to develop recurrent wheezing.

Diagnosis is primarily clinical.4 While different medications are trialled, there is no good evidence for the usual suspects of inhaled salbutamol or oral steroids.

Comprehensive, evidence-based Australasian guidelines have been published by the Paediatric Research in Emergency Departments International Collaborative (PREDICT) Network.

The full guidelines with levels of evidence are freely available on the PREDICT website,1 as are shorter clinical guidelines.2 These have also been published in the peer-reviewed literature.3 Although the guidelines are designed for emergency and inpatient unit practices they are also a valuable resource for general practice.

How common is the condition in the Australian demographic?

Bronchiolitis is highly seasonal with peaks during the winter months. Estimates have been drawn from laboratory data and from data on hospitalisations. However, ascertaining accurate data is a challenge, given that RSV is not a notifiable infectious disease.

Australian national data from 2000-01 showed that approximately 13,500 children were admitted to hospital with bronchiolitis annually. In this study bronchiolitis accounted for 56% of all admissions to Australian hospitals of infants aged less than one year.

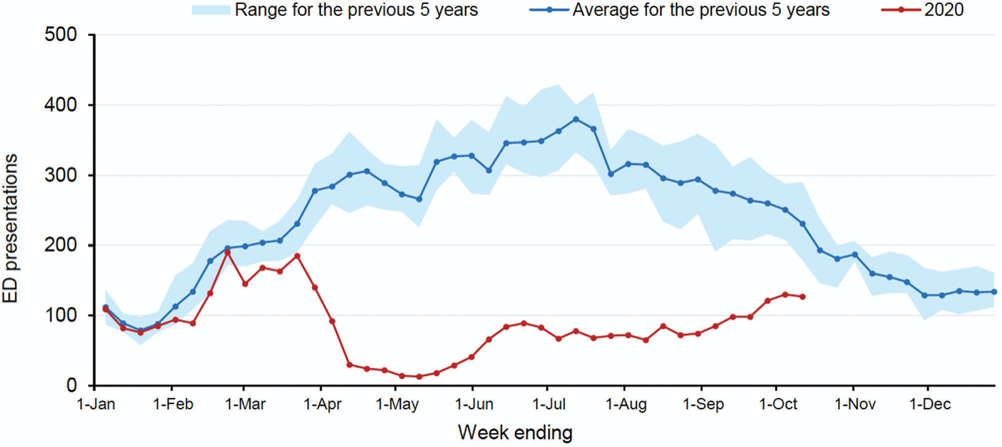

In a more recent study it was estimated that between 2006 and 2015, RSV accounted for over 63,000 hospitalisations in Australia with an RSV-specific principal diagnostic code. Children under five years of age accounted for over 90% of these, with a hospitalisation rate of 418 per 100 000 population. The hospitalisation rate for children under six months of age was much higher at 2224 per 100,000 population.5 These estimates might be even more of a guess with the changing epidemiology of respiratory illnesses and hospitalisations during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Figure 1).

Emergency Department bronchiolitis presentations in NSW by week, to 11 October 2020, compared with previous five years6

Who does this condition chiefly target?

The diagnostic label of bronchiolitis is mainly applicable to infants (0 to 12 months), but may also be applicable to the 12-24 month group.1

What are the main dangers associated with this condition?

Some infants will have mild or minimal respiratory distress just due to nasal congestion as part of a viral upper respiratory tract infection, that is, without lower respiratory tract involvement.

The vast majority of infants with respiratory symptoms and crackles or wheeze with or without varying levels of respiratory distress will have bronchiolitis. However, for all infants one should consider both infectious and non-infectious differential diagnoses.7

Particularly when there is no history of cough or nasal symptoms one should be suspicious of:

- A vascular ring: is there a history of stridor?8

- Foreign body: a suggestive history might not always be present9

- Cardiac failure: is the infant thriving, any added heart sounds or murmurs (hard to hear in an upset or otherwise tachycardic infant), is the liver enlarged, can you feel the femoral pulses?

- Pertussis: is the cough severe or paroxysmal, is there a known exposure?7

- Bacterial pneumonia: is there a high fever? Additionally wheezing is uncommon in these infants4

- Cystic fibrosis: is there chronic cough, failure to thrive, steatorrhoea, ask about family history4

- Chlamydial pneumonia: is there a history of neonatal conjunctivitis, is the cough staccato-like?4

- Fever later in the course of bronchiolitis may be due to otitis media, pneumonia, or a second viral infection.7

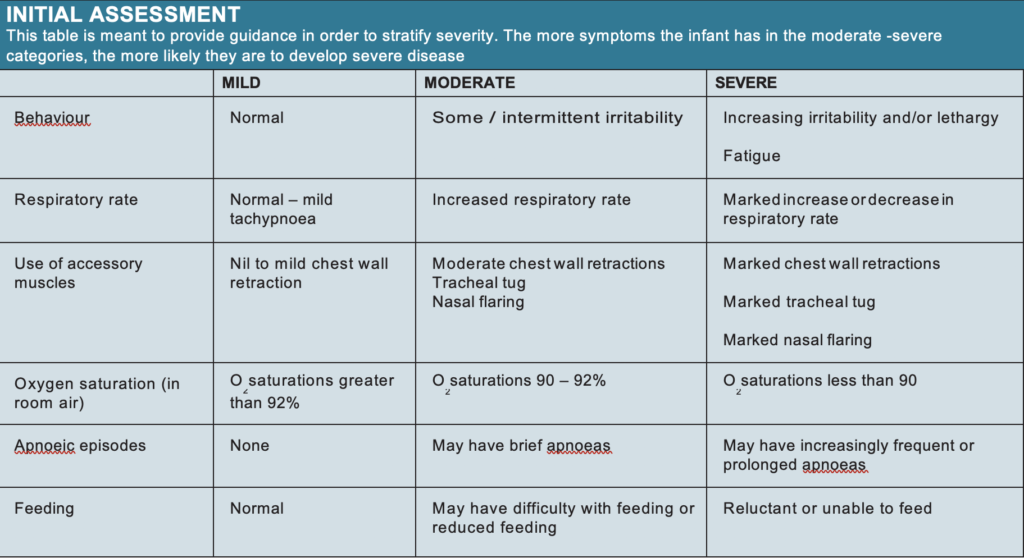

Recognition of the severity of bronchiolitis is critical, as is an understanding of the lack of effectiveness of commonly prescribed treatment.

Any changes in the understanding, diagnosis or treatment of bronchiolitis?

It is hard not to want to “do something,” and we encounter a myriad of hybrid treatment practices.

Management can be confusing for clinicians, given the substantial variation in-hospital adherence to best practice, evidence-based guidelines. A study of more than 3000 children with bronchiolitis admitted to seven Australasian hospitals identified that ineffective interventions and diagnostic tools such as inhaled salbutamol and adrenaline, oral antibiotics and chest X-rays were used in 27% to 48% of children.10 This makes it much harder for the GP to justify to anxious parents that no medications are recommended.

Identifying and diagnosing the condition

Initial symptoms are that of rhinitis and cough. Fever is common, but it is usually not high. The infant may also have tachypnoea, visible respiratory distress and audible wheeze. There may be poor feeding and irritability or lethargy.4 In addition crackles on auscultation may be noted.7 Symptoms usually peak around day two to three. Earlier review in the early part of the illness may be advisable.

Any red flags, symptoms or signs to pick up in the GP visit?

Risk factors for more serious illness are:1,3

- Prematurity (born less than 37 weeks)

- Chronological age at presentation less than 10 weeks

- Postnatal exposure to cigarette smoke

- Breast fed for less than two months

- Failure to thrive

- Chronic lung disease

- Congenital heart disease

- Chronic neurological conditions

- Indigenous ethnicity

- Infants with any of these risk factors are more likely to deteriorate rapidly and require escalation of care.

Any unusual presentations?

Infants with bronchiolitis may present with apnoea. More commonly this will be of sudden onset, as the illness begins; the pathophysiology of this is unknown. The young infant (less than one-month-old term infant or less than 48 weeks’ corrected gestational age preterm infant)11 is at risk. Less commonly apnoea occurs after prolonged respiratory distress.4

What are the most appropriate tests to confirm the diagnosis and assess severity?

As stated above, diagnosis is mainly clinical. The same goes for assessment of severity. (see Table 1) In the infant in the hospital setting with severe bronchiolitis, a chest X-ray may be considered to exclude pneumonia, air leak or cardiac failure. However, in the primary setting, infants this unwell should be sent to the local ED as a matter of urgency.

Pre-COVID-19, virological testing was haphazardly requested although strongly advised against in national guidelines. We would suggest that currently in COVID-19 times, if an infant meets criteria for COVID-19 testing it is worth requesting a respiratory viral panel with the same sample.

Management: which patients should be referred to hospital immediately

Infants can be managed at home with primary review only if feeding and behaviour are normal, if they have a normal heart rate, if respiratory rate is normal or only mildly elevated, if chest recession is absent or just mild, if O2 saturation in room air is over 92%, and there are no apnoeic episodes. Advise small frequent feeds, and provide parental/ carer education,1 which may be facilitated by written information.

A good source of information is the Sydney Children’s Hospital Network factsheet on bronchiolitis. This is freely available,12 provides guidance on the disease process, the lack of a role for medications, and most importantly perhaps, warning signs on when to make a medical appointment and when to seek medical input more urgently. Regular suction is not recommended, even in the inpatient setting.1 For some infants there will be a role for judicious analgesia and fever management. One must, of course, consider the capacity of the parents/carers to understand the possible development of increasing severity and when to re-present. It may be preferable to arrange early review (within 24 hours) or to refer infants even with mild bronchiolitis to the ED if there is concern regarding the capability of the parent/carer to recognise and respond to red flags. It may also be preferable to arrange early review for, or to refer to the ED, the infant with mild bronchiolitis in the presence of risk factors for severe disease, particularly early in the illness.

FOLLOW-UP

What tests would be needed for monitoring from the GP’s perspective?

In the same way that investigations are not required to make the diagnosis from the GP’s perspective, there are no tests for monitoring in primary care. The highest risk of worsening respiratory compromise is in the first 72 hours after the onset of cough and difficulty breathing.13

What is the natural history and short-term prognosis?

Most children are better in 10 to 14 days with perhaps 10% taking three weeks to recover. The case fatality rate is less than 1%, with the majority in children with complex medical conditions.13

Will this child go on to have asthma?

This is unclear. Severe lower respiratory tract infection early in life is a possible risk factor for later asthma, although most children with bronchiolitis do not later develop asthma. It remains unclear if the viruses which cause bronchiolitis set up an immune response leading to later asthma, or whether infants who go on to develop asthma have some as yet undefined predisposition, that has initially manifested as bronchiolitis.13

How can we prevent bronchiolitis?

Breastfeeding and avoiding passive smoking are important preventive measures. Handwashing prevents spread.12 There is no active vaccine for RSV available. Passive immunisation with Palivizumab is recommended for certain high risk groups of less than 35 weeks’ gestation, those with bronchopulmonary dysplasia or with haemodynamically significant congenital heart disease,14 but there are no uniform national guidelines.

FINAL THOUGHTS

While practices are diverse, guidelines are clear.

The infant with mild bronchiolitis can usually be managed in primary care. The presence of risk factors or concern regarding parent/carer capability should prompt consideration of early review or referral to the ED.

Infants with moderate or severe bronchiolitis should be referred to the ED. And as tempting as it may be to prescribe respiratory medications, there is no evidence for inhaled salbutamol, or oral steroids.

Associate Professor Stephen Sze Shing Teo is senior staff specialist paediatrician, Blacktown and Mount Druitt Hospitals in NSW, and Associate Professor, Paediatrics and Child Health, Western Sydney University

Nicola McKay is paediatric clinical nurse consultant, Blacktown and Mount Druitt Hospitals, Western Sydney Local Health District

Disclosure: Nicola McKay was a member of the PREDICT Australasian Bronchiolitis Guideline Multidisciplinary Guideline Development Committee

References

- Australasian Bronchiolitis Guideline (complete version). Available at: https://www.predict.org.au/ publications/2016-pubs/ Accessed 12 October 2020.

- Australasian Bronchiolitis Bedside Clinical Guideline (short version) Available at: https://www.predict.org.au/publica- tions/2016-pubs/ Accessed 20 October 2020.

- O’Brien S, Borland ML, Cotterell E, et al. Australa- sian bronchiolitis guideline. J Paediatr Child Health 2019;55:42-53.

- Panitch H. Bronchiolitis. BMJ Best Practice 2019.

- Saravanos GL, Sheel M, Homaira N, et al. Respira- tory syncytial virus-associated hospitalisations in Australia, 2006-2015. Med J Aust 2019;210:447-53.

- COVID-19 Weekly Surveillance in NSW. Epidemiolog- ical Week 41, ending 10 October 2020. Available at: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/infectious/covid-19/ Documents/covid-19-surveillance-report-20201010.pdf Accessed 23 October 2020.

- Florin TA, Plint AC, Zorc JJ. Viral bronchiolitis. The Lancet 2017;389:211-24.

- Spencer S, Yeoh BH, Van Asperen PP, Fitzgerald DA. Biphasic stridor in infancy. Med J Aust 2004;180:347-9.

- Chatterjee A. Foreign body aspiration. BMJ Best Practice 2020.

- Oakley E, Brys T, Borland M, et al. Medication use in infants admitted with bronchiolitis. Emerg Med Australas 2018;30:389-97.

- Willwerth BM, Harper MB, Greenes DS. Identifying hospitalized infants who have bronchiolitis and are at high risk for apnea. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:441-7.

- Factsheet. Bronchiolitis. Available at: https://www. schn.health.nsw.gov.au/fact-sheets/bronchiolitis Accessed 20 October 2020.

- House SR, SL. Wheezing, Bronchiolitis. amd Bronchitis. In: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics E-Book, Eds: Kliegman, RM; St Geme, J 21st ed Elsevier Philadel- phia 2020.

- Australian Medicine Handbook: Children’s Dosing Companion 2020.