The diabetes epidemic may be being seriously underestimated, both globally and in Australia

The diabetes epidemic is seriously underestimated both globally and in Australia, thanks to inaccurate and inadequate testing, researchers say.

In fact, the real rate of people with diabetes worldwide could be 100 million people higher than official estimates from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), at 520 million instead of 400 million, they wrote.

“There are major and serious gaps in our knowledge of the burden of diabetes, particularly in developing countries, which will have significant unforeseen impacts on national health care systems,” leading diabetes researcher Professor Paul Zimmet said.

However, this gap was not only found in developing countries, he said.

The number of people with diabetes and prediabetes has also been underestimated in Australia, particularly in Indigenous communities, according to the Monash University researcher.

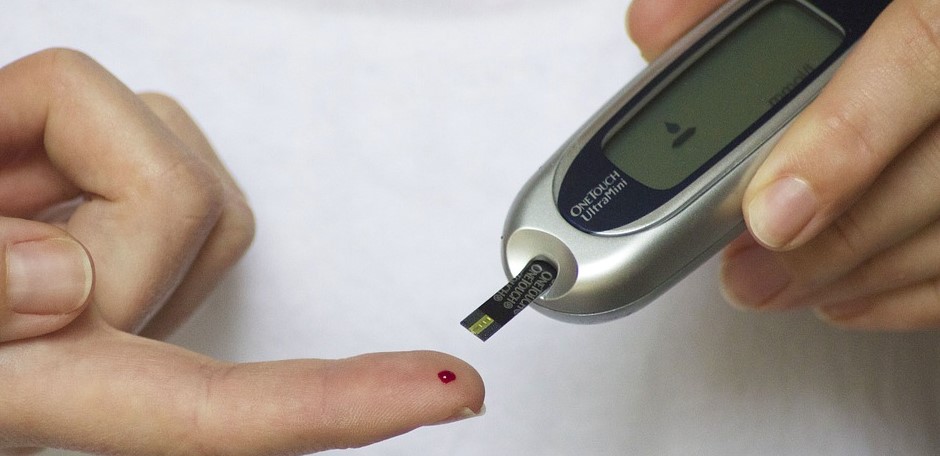

“As the fasting blood sugar has been used as the diagnostic test for these conditions in the Australian 2012-2013 National Health Survey, it is almost certain that the true burden of disease has been underestimated. The resources needed as identified in the Australian 2015 National Diabetes Strategy will therefore be inadequate,” he said.

According to Professor Zimmet and his UK and US colleagues, global strategies to gather information on diabetes rates “fall far short of requirements” and the current estimates are “imprecise, only providing a rough picture, and probably underestimate the disease burden”.

The problem was that organisations such as the WHO and the IDF used different and sometimes inappropriate methods to establish mortality and prevalence rates, but public health policy makers must base their decisions on this data, the authors wrote.

The standard needed to be higher to ensure the best possible public-health planning for one of the largest chronic disease epidemics ever, Professor Zimmet said.

“While the WHO recommends a blood-glucose test both fasting and at two hours after a glucose drink, only the fasting glucose is used in many instances, resulting in an underestimate of at least 25% in the number of new cases of diabetes,” Professor Zimmet said.

Instead, a second glucose challenge should be conducted after the two-hour fast test to confirm the likelihood a patient had diabetes, the authors argue.

Nature Reviews; online 8 July