How can we identify underperforming doctors without subjecting the rest to time-consuming procedures?

The Medical Board of Australia is well aware of the daunting revalidation dilemma: how to identify underperforming doctors without subjecting the rest to time-consuming and needless procedures?

The percentage of underperforming doctors is low. Nevertheless, in the UK all doctors undergo regular appraisals and are ‘revalidated’ every five years if they are deemed up to date and fit to practice.

The UK revalidation system has received its fair share of criticism. A common complaint is that the collegiate appraisal process has been ‘dumbed down’ as it changed from a formative to a summative process.

Other criticism includes the heavy time burden and paperwork, the negative impact on doctors’ wellbeing (while the profession already works in a highly stressful environment), the creation of a tick-box mentality, and a situation where some doctors are avoiding complicated situations and high-risk patients that could get them into trouble.

The good news is that the Australian Medical Board does not seem to want to copy the UK model and instead appears to be looking at countries like Canada or New Zealand, where the focus lies more on self-regulation as opposed to external regulation.

Expect the introduction of an Australian revalidation model in the next two to five years. The question is of course: are we heading in the right direction?

The purpose

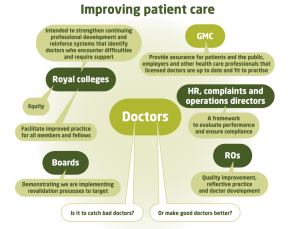

Interestingly, there is still discussion about the purpose of revalidation of doctors (see picture). The overarching principle seems to be improving patient care, but whether it’s about ensuring public safety, ‘catching dodgy doctors’ or making good doctors better, is not always clear.

Some say it’s a bit of everything, which may be true but the problem is: how are we going to develop a revalidation system that does ‘a bit of everything’?

According to the Medical Board of Australia the fundamental purpose of revalidation is to ensure public safety. The Board has proposed a two-pronged approach to achieve this, namely improving continuous professional development (CPD) and identifying at risk doctors:

- To maintain and enhance the performance of doctors practising in Australia through efficient, effective, contemporary, evidence- based CPD relevant to their scope of practice.

- To proactively identify doctors who are either performing poorly or are at risk of performing poorly, assess their performance and when appropriate support their remediation of their practice.

To be fair, I agree our CPD model could be a lot better, focusing more on where we need to improve instead of what we want to improve.

At the same time there are concerns about the Medical Board proposal, especially with regards to the method of finding the underperformers. The Medical Board has recognised many of the issues and is currently consulting with the profession.

Two issues

The overarching problem is that there is little evidence to show that revalidation improves patient outcomes. I can see at least two other major issues:

- Externally enforced actions have less impact than internally-driven change in a collegiate, supportive environment. The colleges, rather than the Medical Board, AHPRA, employers or other parties, should be supported with data and resources to provide skilled remediation.

- The proposed profiling of doctors (e.g. over the of 35, male, trained overseas, previous complaints) appears to be a blunt approach. The tools should be sharpened, focusing more on behaviour and performance. To identify underperforming doctors we need a good screening tool. As Wilson and Jungner outlined fifty years ago, there are several criteria to be met first, to make sure we’re not doing more harm than good, especially as the percentage of underperforming doctors is low and at this stage we’re not 100 percent sure what kind of doctors we are looking for. We should also be careful not to confuse screening and assessment tools.

The way forward

The starting point should be a supportive, non punitive solution. Only when the desired outcomes through collegiate processes are not achieved, should regulators become involved. Any model must be fair, evidence-based and not create large amounts of paperwork.

Here are seven principles I believe are important when moving forward:

- The focus of revalidation should be heavily weighted towards self-regulation and strengthening collegiate education and remediation processes;

- Self-initiated gap and learning needs analysis are effective tools to direct life-long learning, supported by evidence;

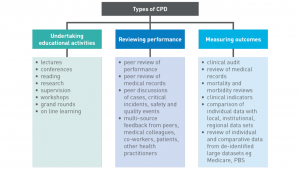

- Peer review, performance review and outcome measurement could be used to strengthen QI&CPD but will require further evaluation;

- Data exchange between agencies and organisations, keeping in mind confidentiality and privacy, could identify underperformers earlier;

- Under performing doctors must be supported, not only via remediation but also looking after the wellbeing of the doctor involved;

- There needs to be clarity and transparency about potential medicolegal use of data collected during the revalidation process;

- The costs involved should not be carried by the profession alone.

And lastly, we really need a less punitive term instead of revalidation.

To make a submission to the Medical Board click here.

This blog was originally published on Doctor’s Bag.

Dr Edwin Kruys is a Queensland GP.