Blaming advances in mobile technologies for increasing rates of sexually transmitted infections may be too simplistic

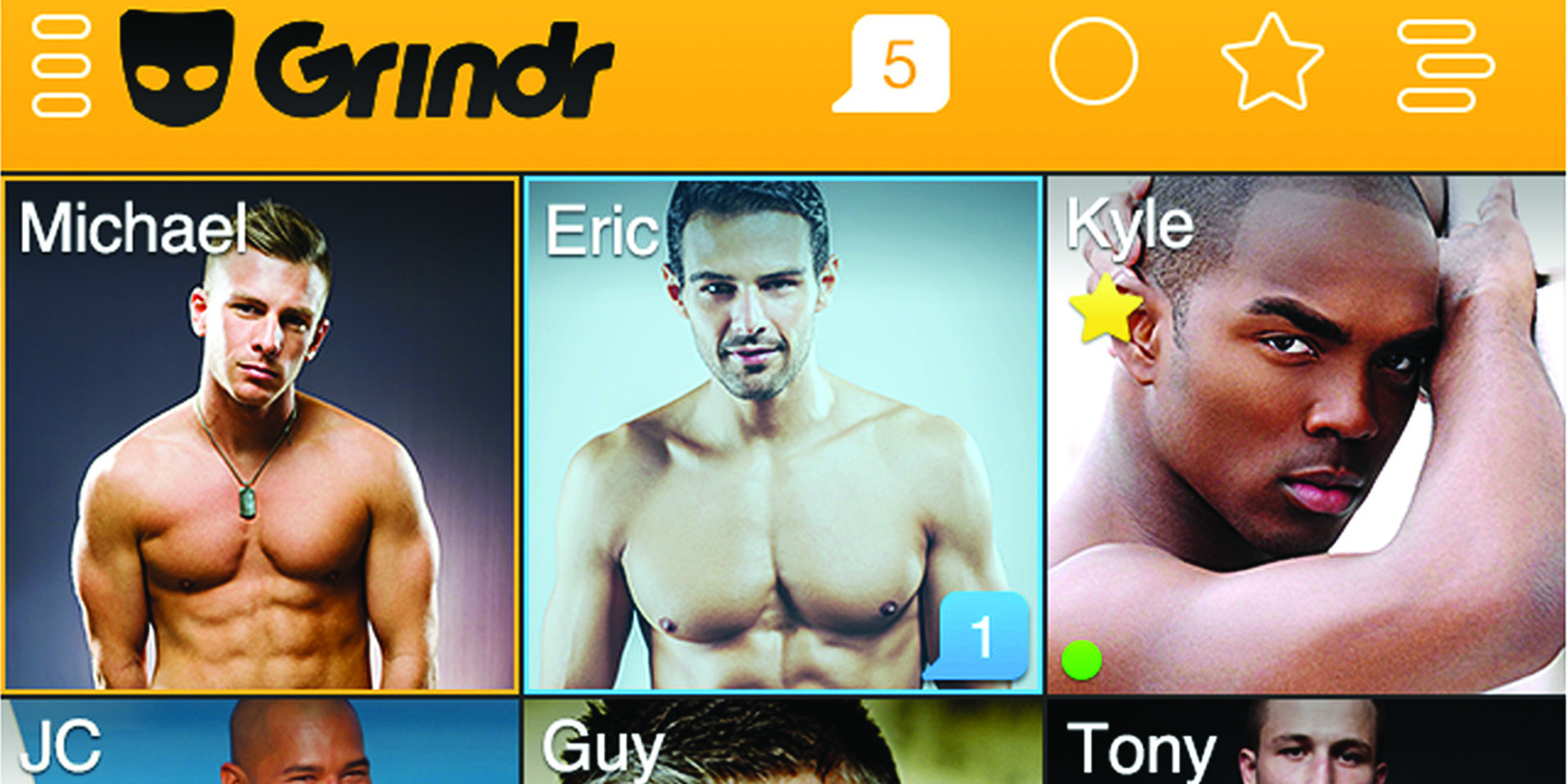

“Hey, let’s bareback,” is the first thing that comes to mind when former Grindr-user Paul discovers that the hook-up app now includes HIV status in a user’s “stats”.

Having people describe themselves as HIV positive or negative, and listing the date of their last test, will encourage people to serosort, that is, pick partners with the same status, he says. But this may give a false sense of security to have unprotected sex.

“You may have had the test, but have seroconverted since,” he points out. “So, I don’t like it really, and I think Grindr doing that gives the whole thing [serosorting] some legitimacy.”

Even assuming serosorting was successful at preventing HIV transmission, it still opens the door for the spread of other STIs.

“People kind of trust Grindr, weirdly,” he says. “Same-sex marriage rally ads would come up at the beginning, and it [Grindr] has sort of played an important role in the community.”

Since its launch in 2009, Grindr has become one of the most-popular dating or hook-up apps for gay and bisexual men, just as Tinder has been for heterosexual men and women.

Grindr now boasts around five million active users per month, globally, while Tinder’s daily active user rate is reported to be twice that.

The difference between these apps and earlier dating websites, such as RSVP or eHarmony, is the apps utilise a smartphone’s GPS to let a user know who’s in the area, and how far away they are, in kilometres, or in Grindr’s case, in metres.

However, the growing popularity of hook-up apps has coincided with a rise in STI rates in many countries, prompting some sexual-health doctors to issue warnings about the technology.

“You are able to turn over partners more quickly with a dating app and the quicker you change partners, the more likely you are to get infections,” Dr Peter Greenhouse told the BBC’s Newsbeat in 2015.

“If enough people change partners quickly, and they’ve got other untreated sexually transmitted infections, it might just start an explosion of HIV in the heterosexual population,” he said. “Apps could do that.”

The view that the internet and mobile phone sex-seeking has led to increased risk taking, and therefore STI rates, is a prevalent one in the field, according to Associate Professor Martin Holt, a researcher in HIV prevention in the Centre for Social Research in Health at UNSW.

Professor Holt manages the Gay Community Periodic Surveys, a pivotal piece of Australia’s behavioural surveillance system for HIV, and he says the thinking is that technology makes partner seeking more efficient and so it mixes up sexual networks. This means that people are introduced to partners they wouldn’t normally meet, and can spread infections in ways they couldn’t previously.

INTERNET REVOLUTION

Back in the early 1980s, at the beginning of the HIV epidemic, men looking for sex with other men would commonly visit adult bookstores and cinemas, or public toilets, known beats, or find partners through personal ads.

But with the introduction of the internet and the growing prevalence of personal computers in the late 1990s, websites where people could find sex started to take over from physical locations.

Early research suggested men using these sites, and later sites specifically dedicated to hooking up, were associated with greater unprotected anal sex, anonymous sex and a higher number of partners, compared with those who didn’t use the internet.

“In San Francisco, a 1999 syphilis outbreak among men who have sex with men was traced back to an online chatroom,” according to the authors of a British survey published this year. “This prompted the internet to be deemed a ‘risk environment’ for STIs.”

Now apps are being viewed in the same light.

The nationally representative study of 15,000 British people found that one in six men had gone online to find sexual partners, and one in 10 women had. In the 35 to 44 years age group, this figure jumped to almost one in three men. And those finding partners online were more likely than their peers to engage in sexually risky behaviours, such as condomless sex with two or more people, concurrent partnerships and having more sexual partners.

The researchers found STI diagnoses and HIV testing were higher among men using online methods of finding partners, although no differences were found in women. One thing to note is that while the STI concern applies to both heterosexual as well as gay app users, research into heterosexual use of these technologies is far scarcer.

These findings are echoed in certain studies that focus specifically on apps, such as a 2014 study of men who have sex with men visiting a Los Angeles sexual health clinic, which found that those who used apps such as Grindr to meet sex partners had higher odds of being diagnosed with gonorrhoea and chlamydia than those who met people only through in-person venues.

However, the question about whether apps increase risk-taking may be an impossible one to prove, according to Professor Christopher Fairley, fellow of the RACP’s chapter of sexual health medicine and director of the Melbourne Sexual Health Centre.

Researchers have difficulty randomly assigning different individuals to one method of hooking up or another. These studies can really only show associations, he says. “People gravitate to different areas.”

Ultimately the literature shows mixed results, with some studies showing an association with apps and risky sexual behaviours and others not.

One suggested explanation for the link between risky behaviour and online sex-seeking is that people who have higher sensation-seeking tendencies are drawn to apps and websites. One Canadian study published this year in Sexual Health found that online sex-seeking men were more than twice as likely to have sex without a condom, even if they didn’t know the partner’s HIV status, which appears to support that hypothesis.

But then the study also found that those men were twice as likely to ask their partner’s status every time, and four times as likely to have been tested for HIV. These men were also nearly twice as likely to use strategic positioning – a technique based on the belief that being a “top” or penetrative partner was less risky for contracting HIV if the “bottom” partner was HIV positive or their status was unknown.

This suggested these men were also working to maintain their sexual health and manage risks, the authors wrote.

Professor Holt says he is suspicious of the argument that technologies are to blame for the increase in STI rates, as a result of their superior efficiency at finding partners.

He says there is a tendency to fall into the trap of thinking that if something is popular then there must be something dangerous about it, “and we’re always a bit suspicious of that without evidence”.

So Professor Holt and his colleagues undertook a novel investigation and separated out the men who only used electronic methods to meet a partner, and compared them with both men who only used physical venues and then men who used a mixture of going out and electronic methods.

“What was really fascinating about it, which runs against that argument that apps increase risk, is that the men who primarily relied on electronic means of meeting each other actually reported fewer risks than other men,” Professor Holt says. “So if they were solely relying on electronic methods, they had fewer partners, they had high levels of condom use and they were less likely to report STIs.”

CAUSAL RELATIONSHIP?

It turned out that the men who reported the highest risks were actually the men who reported the highest range of methods to meet partners. “Which if you think about it, makes sense,” Professor Holt says. “The men who used apps and the internet, went out to bars and went to sex venues and so on had the broadest repertoire in trying to meet partners.”

If they used a broader repertoire to try and meet partners, they had more partners overall.

“It’s a very longstanding finding in any population group that the more sex you have, the more likely you are at some point to report some risks, because you’ve got more opportunities for slip-ups to occur.”

They concluded that it was very unlikely that the apps on their own increased risky sexual behaviour, instead it is probably more likely to be the other way around, Professor Holt says. The people who have the most sex are also the ones most likely to add apps into their sex-seeking repertoire.

So where does all this hand-wringing about apps come from?

Their use has become very popular, but many in the community have no idea how these internet sites and apps actually work.

“It’s something that’s new,” Professor Holt says. “When it emerged in Grindr, and then Tinder in heterosexual people a bit later, people were initially interested, they might have been a bit titillated, but then they get scared.

“Unfortunately, I think that when it’s something they don’t understand, the guardians of our sexual health and morals assume it must be something that is causing problems.”

Then with the backdrop of rising rates of chlamydia, gonorrhoea and some syphilis, some people have seen the growing popularity of those dating apps and assumed the two are causally related.

So what else could be driving the increasing rate of STIs?

Professor Holt says there are no clear answers on what may be driving STI rates higher.

“My colleagues working in epidemiology think that some of this is due to increased screening, so more people are encouraged to test and so we find more STIs.”

But in terms of STIs such as chlamydia and gonorrhoea, the primary driver of those is the amount of sex you have, because that’s when they get passed on, he says.

“What’s funny about gay men is, that as the internet and app use have become the dominant ways that men meet each other, the number of partners they report has fallen over time,” Professor Holt says.

Associate Professor Garrett Prestage, sociologist with the HIV epidemiology and prevention program at the Kirby Institute, says that the notion of there being such a connection “is really predicated on some fairly dodgy assumptions”.

“The first being that the use of online dating and online hook-ups is something unusual – but it’s actually not, that’s what most people do now.”

He says that the institute’s recent research on where gay men have been meeting their long-term partners found the overwhelming majority, two in every three men, have met their boyfriends or partners online.

And the second is that when you compare the number of sex partners gay men have had in their last six months over the last 15 years, the numbers are shrinking.

“And the proportion of men who say they are in a monogamous relationship is actually increasing over that time,” he says. “So, the idea that people are going online because they’re more sexually active is just not supported by the evidence,” he says.

Professor Prestage thinks the alarm is “a bit luddite”. “Yes, people meet online and, yes, they get STIs. But that’s to be expected, because that’s the vehicle by which they meet each other. It’s the same as saying those who have sex are more likely to end up with an STI.”

Professor Holt proposes some theories about why gay men are reporting fewer partners than the generations before, although the research is limited.

“We’ve never come up with a definitive explanation, but one of the things I think is plausible is that the new generations coming through are more focused on serial monogamy, like their heterosexual peers, because there’s more blending of gay and straight social networks now,” he says.

IS TECHNOLOGY MORE EFFICIENT?

The other aspect could be the technology itself getting in the way.

One point the argument comes back to is that the apps are efficient.

Take Paul, who while on a lazy afternoon scrolling through Grindr came across a man seven metres from him. After saying their hellos, the man told Paul he was just waiting in a laundromat doing some washing.

“Wait, the one on Stanmore Road? My apartment is right across from that.” He opened up the blinds. They waved at each other. “Do you want to give me a blowjob?” the man asked. “Sure,” Paul replied, and within 10 minutes the man had come and gone, all while the laundry was still spinning.

Still that’s not the full picture, Professor Holt says. “I’m sure some people find apps very efficient, if they’re lucky.”

But, he also says you can waste an enormous amount of time trying to set up dates using this method alone.

“I actually think it might be a myth that using the internet and apps is efficient,” he says.

Meeting people online is an endless stream of small talk and chatting and trying to organise times to meet up, and people have various motivations for meeting, from casual sex to relationships and anywhere in between.

Gay men, who aren’t in rural areas, have traditionally had options to meet partners that were more efficient than heterosexuals.

“If, rather than sitting on the phone, you think ‘I’ll go to a gay bar’ you can actually eyeball someone [and go home with them], or go to sex venues,” Professor Holt says.

“There are other ways that men can meet each other which actually, time-wise, are more effective.”

The popularity of hook-up and dating apps is all occurring in the context of broader changing sexual dynamics.

“The rise in online technology for hooking up has had a detrimental effect on physical gay venues, with venues closing down,” Professor Prestage says.

“Every time there’s a change in the way people hook up or meet each other, that naturally has to have an impact on what they do with each other and how they engage with each other.”

There’s also the broader backdrop of Australian society to consider.

Results from the national Australian Study of Health and Relationships found people were having sex less frequently than a decade before.

Explanations for this have included the fact that people are working harder overall, and are more stressed over all, leading to a lifestyle less conducive to sex.

“The assumptions about what drives trends in STIs or trends in risk taking don’t stack up – often when you look at the empirical evidence it’s confounding,” Professor Holt points out.

“Gay men are a very well-studied population group in Australia, and they’re actually reporting fewer sexual partners overall, and yet they, like their heterosexual peers, are recording more STIs, so it’s tricky.”

Still, dating apps have an enormous potential to do good as well, with much effort being spent on public-health campaigns using advertising through the immensely popular mediums.

On Grindr, for example, pop up advertisements ask users if they want to find out more about pre-exposure prophylaxis, and can direct them to their closest sexual health clinic.

New technology may have also encouraged more routine disclosure of HIV status.

But when it comes to public perception, it might take some time for the perfect storm of alarm over confusing new technology, and young people having sex, to blow over.