Study finds popular health apps are routinely sharing personal and medical information with third parties, and are hiding that activity

Before you use a medical app or recommend one to a patient, consider that you are probably the product and not the consumer.

A study published in the British Medical Journal has found that popular health apps routinely share personal and medical information with third parties, and are hiding that activity from users.

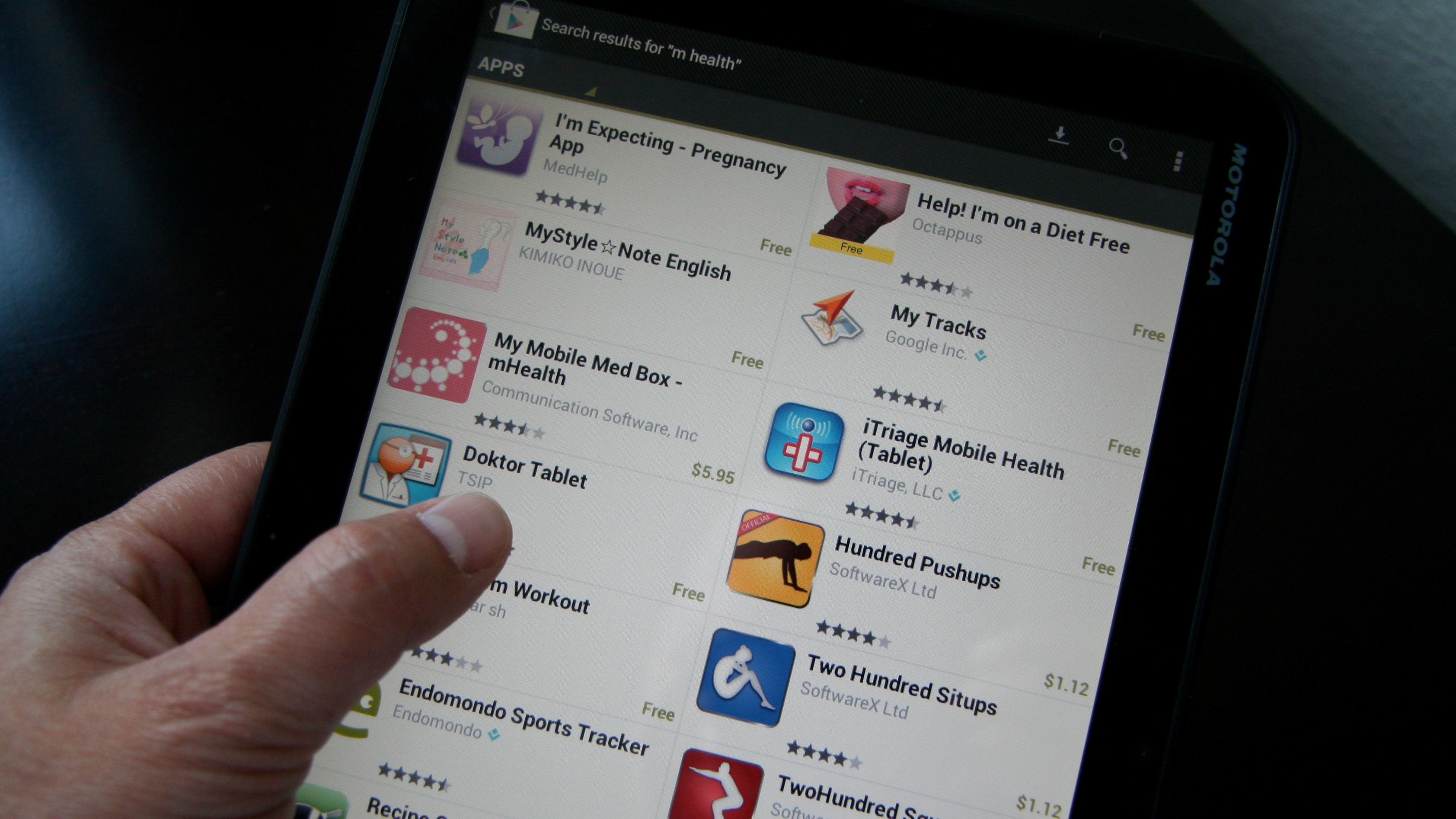

An international team funded by the Sydney Policy Lab at the University of Sydney in partnership with the Australian Communications Consumer Action Network, collected a sample of 24 top-rated or recommended medicines-related apps.

They simulated real-world use from an Australian perspective using dummy profiles, and used a tool designed to detect privacy leaks in Android apps that have been disguised through encryption or encoding.

Nineteen of the 24 apps shared data with third parties including social media platforms, advertising and analytics companies, and in one case, government.

The data could include a user’s name, email address, age, sex, drugs taken, medical conditions, symptoms, browsing history, “personal conditions” such pregnancy or smoking status, and emotional state.

Other seemingly less sensitive data could potentially be combined with other data to identify a user, if not by name: “The semi-persistent Android ID will uniquely identify a user within the Google universe, which has considerable scope and ability to aggregate highly diverse information about the user.”

Amazon and Alphabet, Google’s parent company, received the equal highest volume of user data, followed by Microsoft.

The third parties were further linked to another 237 “fourth parties”, including technology companies such as Alphabet and Facebook, advertising and telecommunications companies and one consumer credit reporting agency. Only three of these fourth-party companies were broadly health related.

This means data could be used not only for highly targeted advertising, but also for algorithmic decisions about insurance premiums, employability or credit.

“As big data features increasingly in all aspects of our lives, privacy will become an important social determinant of health, and regulators should reconsider whether sharing user data for purposes unrelated to the use of a health app, for example, is indeed a legitimate business practice,” the authors write.

“Clinicians should be conscious about the choices they make in relation to their app use and, when recommending apps to consumers, explain the potential for loss of personal privacy as part of informed consent. Privacy regulators should consider that loss of privacy is not a fair cost for the use of digital health services.”

Last month a Wall Street Journal investigation found several health apps were sharing data for use in targeted advertising, without the users’ knowledge. The women’s health app Flo was telling Facebook when users were menstruating or trying to get pregnant, in violation of its own privacy policy.

Last year, the ABC reported that Australia’s biggest appointment-booking app, HealthEngine, had sent hundreds of users’ data to law firm Slater & Gordon as prospective clients for personal injury claims.

Large-scale crowd-sourced analyses have found multiple third-party trackers embedded in apps’ source code, with Alphabet, Facebook and Verizon dominating the tracking ecosystem.