The suicide death of Dr Andrew Bryant, a Brisbane gastroenterologist, last week hit a raw nerve, writes Dr Eric Levi

Episode 1. I’m a surgeon. I’d like to think that I’m resilient and well adjusted, having gone through medical school and rigorous surgical training. I’ve been a doctor for 13 years and much of that period has been spent training to be as good a surgeon as I could ever be. I have great family support, a physician wife who understands my work and I’ve never been diagnosed with a mental illness.

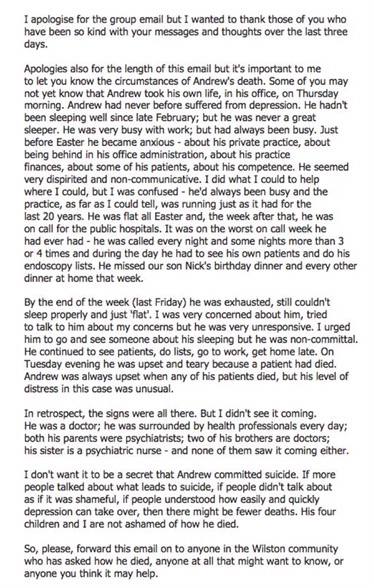

The suicide death of Dr Andrew Bryant, a Brisbane gastroenterologist last week hit a raw nerve. His wife wrote this honest and courageous letter.

Although I’ve never had serious suicidal thoughts, I – like many other doctors – have been through many dark seasons. Depression, anxiety, burnout, suicidality, hopelessness, lethargy, anhedonia, feeling flat, worry, and the like are all different flavours of the same phenomena: the negative human response to internal or external stressors. Of course, the causes are always multifactorial. It cannot and should not be oversimplified to family history, genetics, behavioural deficiencies, bad environment or poor social support.

When I carefully dissect my dark seasons, some common themes often emerge. Work is often the critical exacerbating and perpetuating factor in those dark times. Because as a surgeon I spend the vast majority of my lifetime at work, what happens there influences all other aspects of my life including my marriage, family and social life.

Here are 3 common things that have thrown me into some dark pit of despair:

1. Loss of Control

I have lost control of my days. I had worked in a hospital where I was oncall 24/7, 12 days out of 14. I had fortnightly weekends off. When I was preparing for surgical exams, I’d be working and studying from 6.30am to 10pm everyday, seeing my family only on the weekends for lunch. I had worked in a hospital network that covered 4 campuses and drove 500kms a week when covering these sites. I had worked in a hospital where I didn’t get home for days at a time, sleeping overnight in hospital quarters, outpatient clinic benches and in my car. I used to have my sleeping bag, toiletries and change in the boot of my car because I didn’t know if I was going to make it home some nights. Plans change every single day at work because of emergencies. I can’t even be sure what the next hour will bring when I am on call. You might ask, why can’t you work less? It’s not as easy as that. If I decide to work less, who is going to cover the hospital? If the hospital aren’t employing other doctors, we can’t allow patients to go uncovered. I accept the fact that I have a duty of care to be on call. The intensity and personal damage of these on call periods are often forgotten.

Not only that, we are losing control of health care in general. Everyday, there’s a new form, a new guideline, a new protocol, a new health software, a new policy all dictating, restricting and modifying clinician activities. Some of these policies are written by people who do not see patients. There’s a whole paid industry dedicated to restructuring what doctors and nurses do to reduce costs and increase output.

2. Loss of Support.

Just imagine. I start my days at 6am. I wake up to an email alerting me of the number of discharge summaries that haven’t been completed and the various computer based modules I have to complete (hand washing, privacy, lifting patients, etc). Round starts at 7am. I see 15-20 patients with various travel forms, certificates, scripts that need completing. All to be done via the electronic health system, clunky, not user friendly, takes a long time to log in. Then I start an overbooked operating list at 8am. There are 7 cases booked. I have no say on who gets on the operating list and the order of patients. The first patient haven’t been checked in. The diabetic one is hypoglycaemic. The infant is cranky. The autistic child is running away. The interpreter is not here yet. The computer is still not logging in. The password is expired. I used to be able to arrange the operating list because I know that some operations take longer than others. But now, the bookings office determine that that all my tonsillectomies take 14 minutes because that’s the average time recorded on the computer. The moment I scrub in, the timer starts. The moment I unscrub timer stops. Click. Click. Click. Because the theatre bookings does not take into account the interpreter time, pre-med period or transfer to ICU, the list is running late. The nurse in charge is breathing down my neck to finish on time. I still took about 14 minutes on each case, but the team is delayed by external clinical reasons. The theatre team is anxious to finish, everything is rushed, and mistakes are bound to occur.

In the mean time, I field 12 phone calls from ED, GP and other units. By now there are 3 patients waiting for me in ED and 1 being flown in from another hospital. The operating list is finished late. I rushed to ED, and gulped down a cup of instant coffee. Then I arrive late to the afternoon clinic, which again is overbooked. Clinic nurses are not happy. I see 8-10 patients while taking more calls. I try to discuss complex surgeries with patients but I keep getting interrupted by calls and paperwork. Then I run back to theatre for an emergency case. By this time I’m set up for failure. I’m tired, cranky and my head is full of jobs to do. I do the afternoon round, see more consults, admit more patients and dictate letters. I have taken up to 70 calls on a 24h on call period. By 6pm I’m totally exhausted. I grab a packet of chips, ginger beer, and start working on the papers I was meant to write up. I review the case notes for the next couple of days. I get home between 7-8pm. Grab dinner and put the kids to bed. I get called back in and I take a patient to theatre for an emergency procedure. I come back just after midnight and sleep. I get called four more times between midnight and 6am.

6am. Repeat.

I have lost control of my days and I have lost support. When can I actually find support? I don’t have time to talk to my colleagues about life. I don’t have time with my family. I don’t have time to catch up with friends. Social ties are lost when one stepped into medical school. I’ve lost count of the number of significant life events I have missed (birthdays, anniversaries, reunions, school recitals, first walks, etc.)

I delivered my third child with my own hands because the obstetrician was stuck in a traffic jam. The following morning I went to work because if I didn’t 12 patients have to miss their surgeries, 2 anaesthetists and about 8 nurses will miss out on their day’s income. More importantly, admin would not be happy because a cancelled operating list is a huge financial loss to the hospital.

I know where I can get support, but practically, when and how am I going to get that support?

In addition, doctors who scream for help may be formally reported, therefore having restrictions placed on their practice and then incurring higher medical indemnity fees in some situations. Trainees who ask for help may be labelled as underperforming and have to be commenced on probation or remediation. We may not have practical access to the support that are often advertised.

3. Loss of Meaning

Interestingly, the above physical and emotional stressors are reasonably manageable to me. I’m understanding my own physical and emotional limits. These stressors induce exhaustion, but the excitement of the work and the intellectual challenge of the job bring a lot of personal satisfaction. I do get emotionally shaken at times because I deal with dying cancer patients, emergency airway disasters and sick complex children, but I get by.

I am realising more and more that what brings me greatest distress is the relentless administrative pressure which take away the meaningful clinical engagement I have with my patients. And I wonder if this is what many young doctors are experiencing as well. Medicine used to be a meaningful pursuit. Now it has become a tiresome industry. The joy, purpose and meaning of medicine has been codified, sterilised, protocolised, industrialised and regimented. Doctors are caught in a web of business, no longer a noble vocation. The altruism of young doctors have been replaced by the shackles of efficiency, productivity and key performance indicators.

I have little say in organising my very own operating lists or clinics. Even the power to re-order the operating list has been taken from the surgeon. The thing that I love doing (operating & seeing patients) is being measured, recorded and benchmarked. The clinics are overbooked to get numbers through. The paperwork for each patient encounter is increasing with each passing year. There are so many other non-clinical departments dictating what I should do and how best to do it. The mantra is “cost-effectiveness and increased productivity.”

I went into medicine knowing that I will have to sacrifice much for the sake of my patients. What I am realising is that today in modern medicine, a doctor is just one of the many commodities in this complex industry. It’s no longer about the patient. It’s about the business of hospitals. Patient satisfaction officers, Theatre Utilisation officers, Patient Flow Coordinators. These are all business roles.

As a surgeon I spent a year in a hospital where I smiled on the way to work and I am so grateful for my job. I looked forward to long days because I knew what I was doing was significant. Another year in another hospital, I dreaded going to work. I hated being on call. I was burned out and I couldn’t control my emotions at work and at home. I’m not inherently an offensive or rude person, I’m just a person pushed to the limits and set to fail because of the circumstances around my work. Same surgeon, different jobs. The forces that pushed me to losing control of my emotions are likely the same forces that might push some of us to suicide.

To some hospitals and their business, I’m not a Surgeon. I’m just an employee. Overworked, burned out, replaceable. The noble call to Medicine has been suffocated by the bureaucratic force exerting itself as the medical industry.

Part 2: The Dark Side Awakens

Episode 2. I’m a surgeon. A simple one. I didn’t intend to trigger an outpouring of emotions. I didn’t plan on ever ‘going viral’. But since I wrote The Dark Side of Doctoring 4 days ago, I have had a huge amount of response. On top of the 150,000 hits on my article and the phone calls from several News Agencies, nurses in clinic and theatres have asked if I was OK. I was visited by the Head of ENT Department and the Head of the Division of Surgery. I was contacted by so many fellow doctors, nurses, clinicians from places as far away as Singapore, Sweden and South Africa. My email inbox has been flooded by many doctors, nurses, medical students and their partners who wrote about their own personal struggles in the institutions that they work in. Just take a peek at the comments section to that original article. Heart-breaking.

I have cried over so many of these personal stories. I am seeing many doctors, nurses and medical students in distress. I am seeing a generation of health care workers suffocated and strangulated by their circumstances. (If I haven’t replied, I will!) The conversations are already happening. Much of it online because they’re afraid to do it in real life.

The message from all these responses is clear, “I get you. I feel the same way too. I am not coping with this industrialisation of Medicine.” The article has triggered a universal emotion that many health care workers feel about the state of their vocation. I hope it has catalysed an awareness of this issue in medical institutions where you are.

Now that the Dark Side has Awoken, can we talk about this openly? If you are a Health Administrator, can you please listen to your Clinicians (that includes physiotherapists, audiologists, speech pathologists, Ambulance officers, etc) on the frontlines? We don’t need more programs, initiatives, directives, protocols, videos to watch or numbers to call. We know that those kind of help are available. We need workplace morale to be lifted. If you’re not going to start at the top, we are going to start from the bottom. Elevating workplace morale does not have to be expensive or prescriptive. It can be creative.

If you’re a health institution or health administrator or health leader in anyway, be courageous enough to tackle this elephant in your institution. Be courageous enough to champion this issue. You might save the reputation of your institutions, reduce sick leave, improve workplace environment and possibly save some lives.

I have some ideas about what we can do down at the trenches. We don’t need to halt the Industrialisation of Medicine. We can Humanise it. We can inject compassion into this Business of Medicine. We can regain some measure of control, support and meaning in Medicine. For the sake of our patients and the future generations of health care workers, can we please talk about simple, creative, compassionate human solutions to this problem?

Put up some ideas for discussion please.

Dr Eric Levi is an Australian otolaryngologist, ear & nose & throat, head & neck surgeon. This blog was originally published on Dr Levi’s blog.