It’s hard not to panic when thinking about the looming spectre of antimicrobial resistance. Just as the international community was coming together last month to discuss solutions, our very last line of defence against super-bugs was breached. Chinese researchers discovered resistance to polymixins, the only remaining antibiotics effective against some poly-resistant strains of E. […]

It’s hard not to panic when thinking about the looming spectre of antimicrobial resistance. Just as the international community was coming together last month to discuss solutions, our very last line of defence against super-bugs was breached.

Chinese researchers discovered resistance to polymixins, the only remaining antibiotics effective against some poly-resistant strains of E. Coli and K. pneumoniae.

The current annual death toll to antimicrobial resistant bacteria is 700,000, but this is expected to reach 10 million by 2050. Over 14,000 of these will be in Australia, which would put such infections among the leading three causes of death.

Methicillin-resistent S. Aureus (MRSA) is already well-known for its persistence in hospitals. But experts are particularly worried about the proliferation of Enterobacteriaceae strains resistant to last-line carbapenem antibiotics. These infections have a mortality rate of 40% and scores of cases have already been reported in Australia in the last three years.

“These are truly nightmare bacteria,” said CDC director Dr Thomas Frieden, in in an interview with Vox. “We do have a risk of going into a post-antibiotic era. You’re back to doing things like removing parts of lungs, trying experimental therapies and hoping that the patient’s own immune system kicks back in,” he said. “But we can make a big difference; the good news is we know how to control them.”

To control them we simply need to use fewer antibiotics and reduce the selective pressure for resistance genes. But global trends are going the other way. Between 2000 and 2010 antibiotic consumption increased by 36%, mostly driven by the industrialising countries of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, according to a series of reviews in the Lancet.

It’s easy to point the finger at the agricultural sector for this overuse, as we know that around three quarters of all antibiotics by volume are used in animal husbandry. Flagrant misuse of antibiotics as routine prophylactics or at low doses in animal feed as apparent growth promoters is a huge problem. But the evidence reviewed by the Lancet, and leading Australian experts, implicates the human health sector as an equal driver of antimicrobial resistance overall, given that many bugs only infect people.

A Primary concern

And while hospitals are great places to transmit infections, they are probably not the main source of emergent resistance. “Our best guess is that antibiotic prescribing in hospitals is only 10% of prescribing of all that happens,” says Professor John Turnidge, Senior Medical Advisor of the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. This trend holds everywhere in the developed world,“but we’re a long way behind other countries in counting hospital prescriptions electronically.”

Among OECD countries, Australia is the 8th highest prescriber of antibiotics at 24 defined adult daily doses per 1000 people per day, the international comparator of drug consumption. This is twice the rate of the Netherlands and Sweden. Prescription rates in this country are comparable to those in the US, where the CDC estimates that half of all prescriptions might be unnecessary.

The most-discussed example is the treatment of respiratory tract infections. According to UK and US data between 50 and 71% of presentations for coughs and colds are treated with antibiotics, even though 90% of cases are probably viral in nature. But no doctor wants to mistreat a potential pneumonia or a pertussis infection. Further, European surveys suggest that GPs have little sense that their own prescribing behaviour can contribute to antibiotic resistance in the community. In reality, de novo resistance can be tracked in individual patients.

A lack of public awareness is also to blame for overuse of antibiotics. The WHO has just published survey data showing that two thirds of the community believe that antibiotics can be used to treat colds and flus, and one third that they can stop taking them the moment symptoms abate.

The high prescribing rates in Australia may stem from a system that caters too much to such expectations from patients, according to RACGP spokesperson, Professor Del Mar. “Our fee-for-service structure, in combination with the fact we don’t have patient registration, means that GPs feel vulnerable about losing patients. In this country, if you don’t like what doctor A said you can just go to doctor B in the same afternoon. So doctors will want to do something to please,” says the Professor of Public Health at Bond University.

This perception that ‘customer is always right’ is supported by a survey just published in the British Journal of General Practice reaching most of the practices in England. The study found that practices ‘frugally’ prescribing 25% fewer antibiotics than the national average were ranked five percentile points lower in the GP satisfaction rankings. The authors of the study suggest that this decline in patient satisfaction is not necessarily an unavoidable trade-off of more responsible prescribing for the time being. With intensive education and reassurance of patients it may be possible to offset such sentiments of being ‘short-changed’.

“We’re relatively well-doctored per head of population and that means that access to doctors is easy. In the UK or northern Europe, for example, you can’t get to see a GP for several days unless it’s an emergency. By which time people get to realize that their conditions are self-limiting,” adds Professor Del Mar.

A cultural change

In November, NPS Medicinewise sent letters to all GPs reporting on their individual prescribing patterns of oral antibiotics in an attempt to curb prescribing rates. They also provide graphic handouts to help doctors explain the futility of using antibiotics to treat viral infections. CEO Dr Lynn Weekes says, “patients should be informed that if they have taken antibiotics recently they are twice as likely to have antibiotic-resistant bacteria in their body as someone who has not. And this means that antibiotics are less likely to be effective if needed to treat a severe infection in the future.”

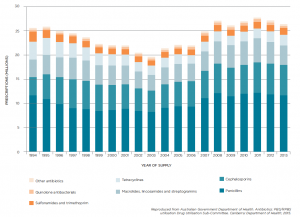

But despite their worthy intent, Professor Turnidge is dismayed at how little impact the NPS campaigns have had over the last 12 years in altering antibiotic prescribing habits (see Figure 1). “The prescribing rate reached a low point around 2002 and 2003 and then it kicked up again and nobody really has a good explanation as to why,” he says. “Just putting things on the sides of buses and trying to persuade people gently is a very slow process.”

In fact, similar education campaigns around the world have on average led to 10% drops in prescription rates and impacts are typically short-lived. Professor Del Mar points to two exceptions. “France and Iceland did them effectively and reduced prescribing by a substantial amount. Maybe we haven’t spent enough money or maybe we haven’t done the campaigns in the right way. They need to be on the scale of campaigns we’ve had in the past for example for HIV awareness.”

Delayed prescribing is one strategy Professor Del Mar has confidence in.

“I do it myself a lot. And we’re doing a trial up here in Queensland to put delay stickers on the prescription as a signal to the pharmacist who is also being brought into this.” Stickers suggest that the patient wait for 24-48 hours after a clinical visit before purchasing the antibiotic, to see whether they haven’t already recovered. Dispensing rates can drop by a third as a result, according to systematic reviews on the practice.

Professor Del Mar is concerned that currently 40% of prescriptions for antimicrobials are written with repeats. The PBS data show that a majority of these are not used, but some repeats are dispensed long after the date of prescription. “This is clear misuse. The Department of Health is actually considering making prescriptions for antibiotics expire after a few weeks, rather than 12 months.”

“In the future I think that it may be necessary to restrict certain antibiotics in a more draconian way, like authority prescribing. It’s a pain in the neck and GPs hate doing it, but it cuts down on the prescribing dramatically,” says Professor Del Mar. In hospital settings too, restrictive interventions have been shown to be more effective than persuasive ones at changing prescribing habits over a longer term, and reducing antimicrobial resistance rates.

Almost half the 29 million prescriptions for antibiotics written between 2013-2014 were for the beta lactams amoxicillin (with and without clavulanic acid) and cephalexin. CEO Dr Lynn Weekes, recommends use of more selective drugs where possible. “Fewer than 10% of beta-lactam prescriptions in Australia are for narrow spectrum antibiotics. Exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics is a driver for antibiotic resistance.”

The Australian paradox

Australia for the moment is a ‘lucky country’, according to a recent review by Professor Peter Collignon, director of ACT Pathology and ANU academic. “Despite fairly high per capita antibiotic usage we have for most bacteria amongst the lowest resistance rates in the world,” he writes. Of this ‘Australian paradox’ Professor Turnidge says, “It might be our isolation, or low population density. It’s impossible to say, but it won’t stay like that.”

Professor Turnidge points to the tight restriction of fluoroquinolones such as ciproflaxin to a single indication in the 1990s. “We’re the only country to have done that and it’s delayed the emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance in Australia by an extra 10 or 15 years compared to other countries,” he explains.

“Unfortunately the battle is now being lost because fluoroquinolone resistance is linked to other resistance genes that are being selected for.” In addition, half of subjects returning to Australia from overseas have been found to carry E. coli strains resistant to fluoroquinolones, third-generation cephalosporins or gentamicin. The rate of fluoroquinolone resistance in E. coli isolates from different European countries ranges from about 15% to 80% and shows a stark inverse correlation with the use of these antibiotics.

Apart from antibiotic use, hygiene measures such as alcohol rubs for hands, and better management of central venous lines and catheters, shave led to a 60% reduction in all S. aureus infections in hospitals over 12 years, says Professor Turnidge. But despite these advances against transmission rates overall, methicillin-resistant strains of S. aureus are doggedly entrenched.

“The MRSA story is getting flipped on its head somewhat. There was a dominant strain of MRSA in our eastern state hospitals but the change in practice had significant impact on that. At the same time another strain of MRSA, and the English strain which is well established in our nursing homes, are sort of taking over in the community,” explains Professor Turnidge.

According to a 2012 surveillance study he co-authored with Professor Collignon for the Australian Group on Antimicrobial Resistance more than one in ten S. aureus infections in patients attending general practice were methicillin-resistant. In emergency departments and outpatient clinics the figure was one in five and for patients in long term care facilities the rate was twice as high again.

Into the wild

Vigilance and coordination are required across all sectors to circumvent a bleak future, explains one review in the Lancet series. Even a withdrawal of selective pressure by reducing antimicrobial use does not necessarily lead to an abolition of resistance genes, as they may confer little cost to the organism. The best we can hope for is to limit the proliferation of resistant strains.

But there is hope for new antibiotic sources. In January, encouraging findings were published describing the isolation of 25 new antibiotics from soil samples. One of these in particular, dubbed teixobactin, was tested in lab cultures without the emergence of resistance.

Researchers have also scraped around a thousand uncharacterised bacterial strains from the walls of caves, in the hope that novel weapons for intramicrobial warfare have been bred in these isolated environments. To date this work has found resistance to all known antibiotic classes even among these pristine colonies, but the majority of samples remain to be studied.

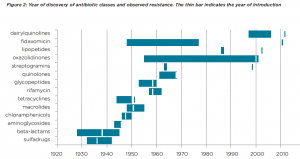

An important hurdle to overcome will be the incentivisation of research and development, says one of the Lancet authors, Professor John-Arne Røttingen. Pharmaceutical companies have been loathe to get involved in antibiotic production since resistance has typically emerged within a few years of the discovery of every new antibiotic (see Figure 2). This doesn’t make for a very lucrative commercial product.

“We need to completely rethink the way that research into antimicrobials is funded, starting by decoupling innovation in drug development from sales,” says Professor Røttingen of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. “At the moment, the economic value of new antimicrobial drugs doesn’t materialise until the old drugs have failed, by which time it is too late. The funding of these drugs needs to be driven by public health needs, not by profit.”