A couple of education sessions and a handbook can’t overcome a lifetime of cultural privilege

When Dr Mark Lock was 20 years old, his grandmother found her mother through an Aboriginal organisation called Linkup NSW.

Dr Lock (PhD), a Ngiyampaa academic who researches cultural safety, describes this sudden reconnection with his family as a “lightning-rod moment”.

“She was stolen,” he says. “So, my great grandmother was taken from Melville Island off the north coast of the Northern Territory and transported down to Menindee in the top north-west corner of New South Wales.

“And then she was raped. And my nan was born from that assault. And then my mum had me. It’s a typical story actually. Quite confronting when I think about it. That’s where I’ve come from.”

Having shared his story, Dr Lock politely turned the spotlight on me and asked: What is your cultural background?

I paused, feeling a little thrown. I didn’t really have an answer to that question.

My background is bland and boring – white, Anglo-Saxon, a descendent of convicts and colonials. I am almost never called upon to describe my culture. My culture is so dominant that I forget it’s even a culture. It becomes white noise. How privileged is that?

IGNORING CULTURE

Indigenous Australian health advocates have been trying to convince doctors to notice culture – their own and others – for many years, with limited success.

When you belong to the mainstream culture, the healthcare system just seems normal, vanilla even. Everything is familiar and predictable; the staff look like you and everyone knows what they’re supposed to be doing.

It’s easy to forget that every interpersonal interaction in a GP clinic or hospital is being governed by an unwritten, intricate set of cultural rules.

It’s easy to forget that this system has been deliberately planned out so that it makes someone with your specific cultural background feel completely at home.

Unfortunately, many Indigenous people do not feel that way.

“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a lot of issues with going to hospital because they are really alienating environments, not just the physical space but the attitudes of health professionals and just the fact that they are colonially constructed organisations,” says Dr Lock.

“Hospitals are very hierarchical in their decision-making. It’s ‘you come to this physical structure if you need help’. I’m sitting outside a hospital now and there’s not one indicator that they care or respect Aboriginal people at this hospital. There are no flags. There is no art. There’s nothing.”

Indigenous Australians have an average life expectancy that is around eight years less (and a mortality rate that is 1.8 times more) than non-Indigenous Australians. And Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are six times more likely to die by suicide.

They are at higher risk of chronic conditions like obesity, alcohol use disorder, heart disease and diabetes while multimorbidity is 2.6 times higher for Aboriginal people than for the general population.

The culture clash keeping Indigenous people away from healthcare is a major part of the problem, says Dr Lock.

The founder and director of the research company, Committix, and administrator of the Facebook group, Cultural Safety and Security, Dr Lock says cultural blindness is baked into the healthcare system at a policy level.

For example, his research showed that no Indigenous people were asked about open disclosure policies in Australian hospitals, even though millions of dollars were spent finding out how the general public felt about the issue.

This might just be one little policy area, but cultural bias starts to accrue in the system when thousands of policy decisions are made without a thought being given to Australia’s First Peoples, he says.

What would open disclosure policy look like if health-policy makers had bothered to ask Indigenous people about it?

“I think with 250 nations, that means 250 different types of responses,” says Dr Lock.

“And I don’t see a problem with that because we have a hospital virtually in every large or medium-sized community and the hospital should be able to engage with the local community. That’s a simple process. I don’t know why it hasn’t been done.”

CAN TRAINING WORK?

In Sydney and Melbourne, the effort to enlighten urban GPs about the importance of culture has formalised into the Ways of Thinking and Ways of Doing (WoTWoD) cultural respect framework and program run by UNSW in Sydney and the University of Melbourne. But the program failed to make any measurable difference to the cultural competency of practice staff, a one-year randomised trial involving 56 GP clinics showed. It seems that a half-day education session, a cultural mentor and a handbook can’t overcome a lifetime of cultural privilege.

The intervention did not significantly improve cultural quotient scores of practice staff or increase the use of the Indigenous health MBS item number 715.

So what went wrong?

The intervention seemed to be making an impact in the 2015 pilot study.

GPs who were interviewed as part of the pilot study described the program as “very useful” and that Indigenous people coming to the practice felt more comfortable identifying themselves as such.

One year probably wasn’t long enough for the program to produce measurable outcomes, says Professor Siaw-Teng Liaw, a professor of general practice at UNSW who led the program.

But it was a condition of the NHMRC grant that the researchers published their findings, whether positive and negative, which they did in the MJA.

The aim of the intervention was to change the culture of general practice so that the reception area and the consultation room felt like a warm, welcoming environment for Indigenous Australians living in urban areas.

As part of the program, practice staff were taken through 10 scenarios illustrating respectful and disrespectful cross-cultural behaviour in primary care.

In one scenario, staff were quick to make assumptions about alcoholism based on racial stereotypes, and Aboriginal patients were quick to take offence even though the action was not intended to be racist.

In more positive scenarios, practice staff discreetly helped an Indigenous patient with limited literacy fill out a patient form and displayed posters and flyers inviting patients to identify as Indigenous. The education program also unpacked why it was difficult for some Indigenous patients to adhere to treatment plans.

In one scenario, an Indigenous woman is overwhelmed by her diabetes diagnosis and tells her doctor to “get stuffed”. In another, an Indigenous single father of two children with a demanding job says, “enough is enough” and refuses to add any more steps to his insulin therapy.

The WoTWoD booklet preaches empathy and practical medicine.

Is the insulin regimen too complicated? Simplify it. Does the patient forget to take the medication? Seek family support. Is it too expensive? Look into cheaper options. Are you breaking some bad news? Use the SPIKES protocol.

More than 50% of Aboriginal Australians live in urban and regional areas and they are likely to go to mainstream general practices, the WoTWoD booklet says.

But often Indigenous people don’t tell their doctor that they are Indigenous because they fear racial bias will influence how they are treated.

The WoTWoD program has the ambitious aim of transforming GP clinics into safer spaces through continual training, self-assessment, reflection and community outreach.

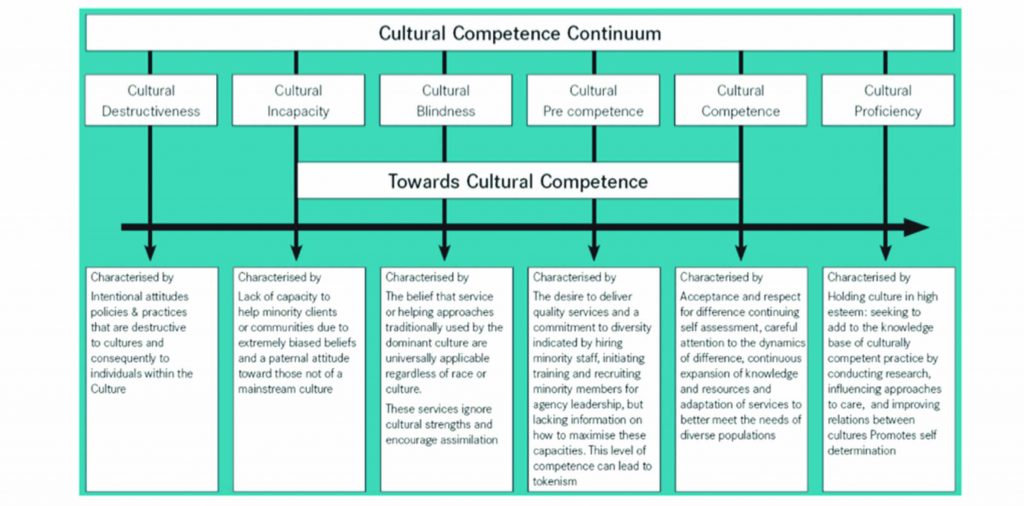

“But you can’t just take a cultural safety course for one hour and everything’s fine,” says Dr Lock. Cultural competency is a lifelong learning process.

That doesn’t mean that little things can’t make a big difference, however.

POWERFUL GESTURES

“My local GP is fab, but he didn’t have anything about Aboriginal people up in his practice until I said, ‘I’m Aboriginal’,” says Dr Lock. “It was a five-minute consultation, but 25 minutes later we were still yarning. It changed the way he did things.

“A few months later, I went there, and he had an Aboriginal poster on the wall. He had a sticker on his front desk saying, ‘We acknowledge and pay respect to the local Awabakal people’.

“And so I noticed that shift. As great as he was, he still learned something with me.”

It only takes a moment to communicate respect when a patient walks in the door, says Melanie Robinson, the CEO of CATSINaM, an organisation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses and midwives with more than 1300 members.

“Sometimes receptionists and clinicians are busy doing other things, but they need to take that moment to stop and acknowledge that that person is there,” she says.

“It’s even just looking up and smiling and nodding your head. It sounds really simple, but it’s actually really powerful. That can affect the whole experience.”

Ms Robinson grew up in the Ngallagunda community in Derby, a little town in the Kimberley in Western Australia. Her grandmother was born in Halls Creek and was taken to the Beagle Bay Mission north of Broome as part of the Stolen Generation.

Cultural respect programs are not effective unless they “really ch ange a person”, says Dr Megan Williams (PhD), a senior lecturer at UTS in Indigenous health and a Wiradjuri person.

“When we do education, we talk about a lens shift,” she says.

“We put people on a journey to really understand who they are and what informs their lens and what might need to be disrupted in order for a new understanding to be brought.

“Unless a person has that lens shift, unless the experience is deep enough for a person to be changed by it, they will behave the same.

“So, probably those GPs [in the WoDWoT program] had more information about Aboriginal people but couldn’t incorporate Aboriginal people’s ways of doing things to therefore engage Aboriginal people.”

We will never truly understand another person’s perspective until we respect their culture enough to deeply immerse ourselves in it, she says.

“You can’t get there unless you do that immersive work and you don’t do that immersive work unless you respect Aboriginal peoples as having something to offer,” she says. “And I think that’s the crux of the issue.”

Many healthcare initiatives aim to close the gap by making Indigenous people assimilate into the mainstream, she says.

The general message is: “We will bring Aboriginal information in, but we won’t change how we do things”, says Dr Williams.

Australian society as a whole is missing out by failing to appreciate what Indigenous people have to offer, she says.

“I think that Aboriginal peoples’ ways are far better, far superior, far cheaper than mainstream.

“Indigenous models of care are wholistic and intergenerational and they encompass physical, mental, spiritual, emotional and environmental care, not just the physical.

“So, what we call comprehensive primary healthcare. Our Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations have used that term for decades.”

Interestingly, this concept is very similar to the term “multidisciplinary care”, which is being flashed about by primary care academics as if it were an entirely new invention, she says.

REINVENTING THE WHEEL

Aboriginal health services have been delivering culturally respectful healthcare to Indigenous Australians since the first centre opened in Redfern in Sydney in 1971.

There are now around 150 Aboriginal health services nationwide.

These services operate very differently to mainstream GP clinics. Services are owned and run by the local community and how they operate locally varies widely.

Patients can often drop in at any time. At some clinics, a range of bulk-billing specialists regularly see patients on-site – with everything from psychiatry to dentistry covered.

Some clinics offer subsidised fruit and vegetable boxes, transport, support with housing and connection with the community facilitated by Aboriginal Health Workers.

“There are a whole range of services that are much broader than just me and my prescription pad,” says Dr Tim Senior, a GP at the Tharawal Aboriginal Medical Service in Campbelltown in NSW.

Working with disadvantaged Indigenous patients is clinically complex, as patients often present with multimorbidity at a much younger age, he says.

Cultural differences are important to understand too, as this can significantly affect patient wellbeing, he says.

“An example I had was a young woman who came to see me who was being treated for depression. She’d had a family member murdered in Queensland.

“What was really distressing her was that the death hadn’t been handled in a culturally appropriate way. They didn’t have the correct burial and smoking ceremony.

“That’s important for her distress, but that’s not something I can manage medically. We need someone like an elder to be able to go through that with her.”

Non-Indigenous GPs can’t just guess what the cultural issues might be, so they have to collaborate with Aboriginal Health Workers, says Dr Senior. “I would never get that on my own.”

It’s hard for mainstream GP clinics to replicate the experience of visiting an Aboriginal Health Service because it takes longer consultations and Medicare really still pays best for shorter consultations, he says.

“GPs sometimes take a hit in income for doing this well,” he says.

CONFUSING TERMINOLOGY

The term “cultural safety” has taken off in the health literature, along with a cluster of doppelgangers such as cultural responsiveness, cultural respect, cultural awareness, cultural competence and cultural security.

These terms seem to be used interchangeably in Australia, with some groups favouring one term over another.

AHPRA is currently running a public consultation to create a national baseline definition for “cultural safety”.

“The way that terminology is used can be confusing,” says AHPRA’s strategy group co-chair, Professor Gregory Phillips.

“Given the large variance in the use and meaning of these terms in different contexts in Australia, AHPRA have identified a need to ensure consistency in terminology,” he says.

The important thing to recognise is that “cultural safety is not culture”, he says. “Cultural safety, in a sense, is a euphemism for unconscious bias, discrimination and racism either in individuals or systems.”

The federal Department of Health produced a national cultural respect framework in 2016, “but it’s sort of a quick and dirty job that just sort of got dumped on the internet with no kind of consultation and nobody was really clear where it came from”, says Professor Gregory Phillips, a descendant of the Waanyi people of north-west Queensland and the Jaru people of the Kimberly in Western Australia.

“The intention was probably meant well, but what it has unwittingly done is keep the focus on Aboriginal people and our culture as the problem,” he says.

“The Aboriginal health groups within AHPRA that are partnering with the strategy group don’t like the term cultural respect for that reason.”

The term “cultural respect” puts all the emphasis on culture, when many of the barriers and complications in Indigenous health don’t actually relate to culture.

While culture is an important factor, the impacts of intergenerational trauma and the socio-economic disadvantages that stem from a history of dispossession are often the really pressing issues in Indigenous health.

“I had one patient who had diabetes that was out of control,” says Dr Nadeem Siddiqui, the executive director of clinical services and a GP at Winnunga Nimmityjah Aboriginal Health and Community Services in the ACT.

“Why was it out of control? Because she couldn’t pay her rent and she had six children. So, she had to put the young children with family and the oldest child, who was close to 16, was living with her in her car.

“And, guess what? Her diabetes was out of control because she wasn’t able to focus on it. There’s not much culture there in terms of what I need to do. It’s more to do with social determinant issues. She couldn’t pay for her housing.”

Dr Siddiqui grew up in the UK and has Indian heritage.

“I would say – having been here six years, full-time engrossed in service delivery for Aboriginal patients in an urban setting – that, alas, culture only plays a minor role due to cultural identity loss, loss of language stemming from historic reasons such as the Stolen Generations and missionary activity,” he says.

“So, probably that’s why we don’t see the same aspects as in the Northern Territory, where those communities have been able to preserve their language and therefore culture,” says Dr Siddiqui.

But, regardless of whether the source of the difference between clinician and patient is cultural, historical or socio-economic, the pathway to sensitivity is the same.

“We ask about the patient’s ideas, their concerns and expectations about their health and why they are here to see us,” says Dr Siddiqui.

“I’ve always found that as a very useful guide in terms of being able to address people’s concepts of wellbeing.

“But you have to be in tune with that. So, our consultations are much longer. The standard consultation should be half an hour on average. Anything shorter, we compromise on care.”