Non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy is a complex area of diagnosis usually requiring specialist help for managing allergen avoidance

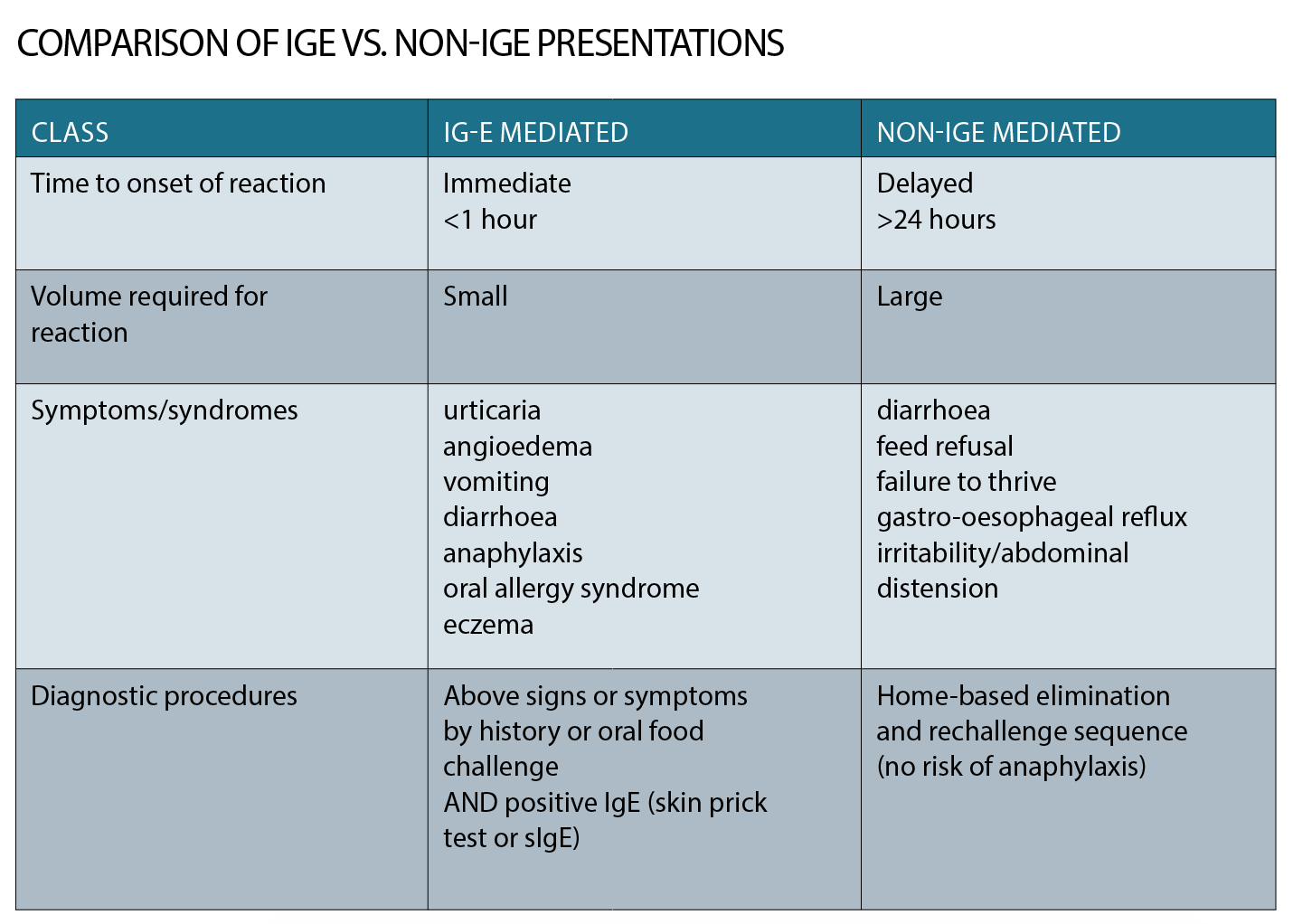

Cow’s milk allergy is defined as an adverse reaction to cow’s milk protein that is mediated by the immune system. There are two recognised forms of cow’s milk allergy: IgE-mediated and non-IgE mediated, with up to 5 to 10% of infants affected by one or the other in the first year of life. The former is well-described, easily diagnosed and managed, with significant understanding about underpinning mechanism.

The main clinical distinction between the two conditions is that IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy carries a risk of anaphylaxis – the most severe form of allergic reaction – which can be life-threatening, while non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy carries no risk of anaphylaxis and signs and symptoms related to this group of conditions are mostly referrable to the gastrointestinal tract.

The distinction between non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy and IgE-mediated is essentially made based on history with non-IgE mediated allergies presenting with delayed onset of symptoms after a new food is introduced into the diet while IgE mediated reactions occur within minutes of ingestion of the offending food. Lactose intolerance is a separate condition that relates to a relative deficiency of the enzyme lactase to break down the milk sugar, but can also present with gastrointestinal symptoms. This article discusses how to recognise and manage each of these conditions and when to refer.

IgE mediated cows’ milk allergy

IgE-mediated food allergy reactions present within minutes of ingestion. They include skin erythema and flushing, urticaria (hives), angioedema (facial, peri-orbital and pre-oral), vomiting, and, in the most severe form, anaphylaxis. The diagnosis of IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy is relatively straightforward and based on a clear history of an acute allergic reaction upon unequivocal exposure to cow’s milk – usually on the first or second exposure, including via exposure through cow’s milk secreted through breast milk.

Diagnosis is confirmed through detection of cow’s milk IgE antibody – either through blood tests (serum specific IgE to cow’s milk) or skin prick testing (through allergy services). Most IgE-mediated allergic reactions occur following exposure to a relatively small quantity of food (a bite or two may be sufficient – or a few mls in the case of cow’s milk) and most occur within five to 10 minutes of ingestion. However, some reactions may take up to one to two hours to develop, especially if the allergen is in the cooked form.

Management of IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy involves allergen avoidance and provision of an allergy action plan that may include prescription of an Epipen. Ensuring adequate calcium intake is particularly important in the first year of life when infants have a milk-predominant diet.

NON-IgE mediated cows’ milk allergy

Non-IgE mediated (or delayed) cow’s milk allergy can present at any age although, similar to IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy, is more common in young infants and children. It is more likely to be missed or the diagnosis delayed compared with IgE mediated food allergy – partly because the symptoms are often reasonably non-specific and can be mistaken for other conditions such as reflux or colic.

Non IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy is an umbrella term for a number of different conditions that are generally referrable to the gastrointestinal tract including cow’s milk induced gastro-oesophageal reflux, eosinophilic oesophagitis, enteropathy, proctocolitis and food protein induced enterocolitis (FPIES).

Diagnosis

In general, diagnosis of non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy is based on suspicion of the condition following a history of symptom onset soon after the introduction of a new food into the diet.

Symptoms of non-IgE are generally delayed and present with gastrointestinal manifestations, including vomiting, diarrhoea, bloating and irritability, poor feeding and failure to thrive. It is important to assess for symptoms and signs of IgE-mediated (immediate allergic reactions) by a thorough history to ensure risk of anaphylaxis associated with a mixed IgE/non-IgE cow’s milk allergy is ruled out.

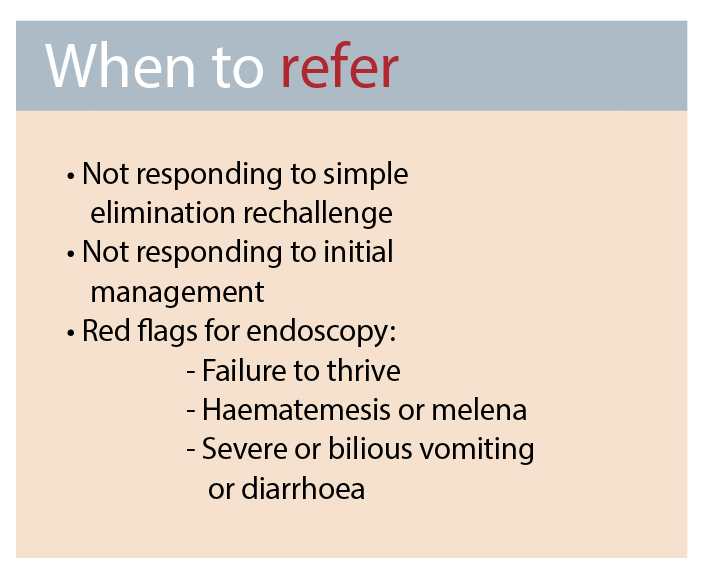

If a mixed set of symptoms is present, it is appropriate to refer to an allergist to consider skin prick testing or sIgE to rule out co-existent IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy. Some non-IgE mediated conditions, such as FPIES, have pathognomic histories, as outlined in the table at right.

Some cow’s milk-induced conditions, such as eosinophilic oesophagitis and severe gastro-oesophaeal reflux disease, require endoscopic examination and biopsy for confirmation. However, the other non-IgE mediated conditions rely on the general principle of elimination and re-challenge, usually in a home setting, provided the risk of an IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy (i.e. the reaction is not immediately after food ingestion) has been considered and excluded.

Cow’s milk and soy are the two foods most commonly associated with non IgE-mediated food allergy. As such, these conditions (with the exception of eosinophilic oesophagitis) usually present in the first year of life. Some might present later in life with a history of either sub-clinical symptoms or covert avoidance (for instance if an infant refuses bottle, or if family eating patterns are soy not cow’s milk predominant). As such an early life history of dietary intake is important in all cases of delayed cow’s milk allergy to assess whether the problem has been long-standing or sub-clinical.

Elimination/rechallenge sequences of one food at a time to only one to two food groups (for example cow’s milk and soy) can be easily undertaken by GPs and general paediatricians.

Assistance from a registered dietician can be helpful in ensuring both appropriate plans for allergen avoidance, (including how to read labels and potential menu suggestions) as well as assistance in ensuring appropriate nutrition such as calcium replacement when avoiding dairy. If more than one food group requires elimination, referral to a specialist allergist or gastroenterologist is appropriate.

Elimination for two to four weeks followed by re-introduction in a careful stepwise progression are the essential steps of the elimination/rechallenge sequence. Commencing with 5ml of cow’s milk and doubling each day until a full serve is achieved is an appropriate non-IgE home introduction plan.

It is important to engage parents at the start of this diagnostic manoeuvre to ensure they understand the rechallenge step of this sequence. This is essential to ruling out a coincidental settling of symptoms that is not due to allergen elimination.

Management

The mainstay of management of non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy is allergen avoidance. However, unlike allergen avoidance for IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy, elimination of allergen from baked goods is not critical and is usually reserved for those who do not respond to initial allergen elimination from the general diet.

Cow’s milk proteins are secreted through breastmilk and can result in a range of delayed cow’s milk allergy. The one exception to this general rule is FPIES which has rarely been reported in an exclusively breastfed baby – probably because the concentration of cow’s milk protein in breastmilk is too low to trigger an FPIES reaction, or the protein has been altered in breastmilk so that an immunological response is not elicited.

Alternatively, breastmilk may provide immunomodulatory factors that prevent an FPIES reaction to an allergen present in the breastmilk. Resolution of symptoms (at least partially) is usually evident within a few days of allergen elimination, either from the mother or infant’s diet, but may take up to two weeks. If symptoms have improved, but not resolved, it may be useful to recheck the patient’s allergen avoidance regime and to potentially move to allergen avoidance in baked/manufactured goods.

Further elimination of a more restricted diet can continue for a further two weeks, but if there is no improvement then the food should be re-introduced into the diet.

Occasionally patients do not report improvement on allergen elimination but do report aggravation of symptoms upon re-introduction. In these cases, a repeat elimination/rechallenge sequence should be undertaken to confirm the diagnosis.

If symptoms are re-elicited on challenge, the diagnosis is presumed and allergen avoidance resumed. Infants should continue allergen avoidance with regular rechallenge/elimination every six to 12 months, except in the case of FPIES and eosinophilic oesophagitis, which should be referred to a specialist for evaluation. In the former, oral food challenges should only occur in hospital under medical supervision, and in the latter condition, need to be undertaken in partnership with a gastroenterologist to decide whether recurrence of mucosal abnormalities have occurred in the absence of symptoms.

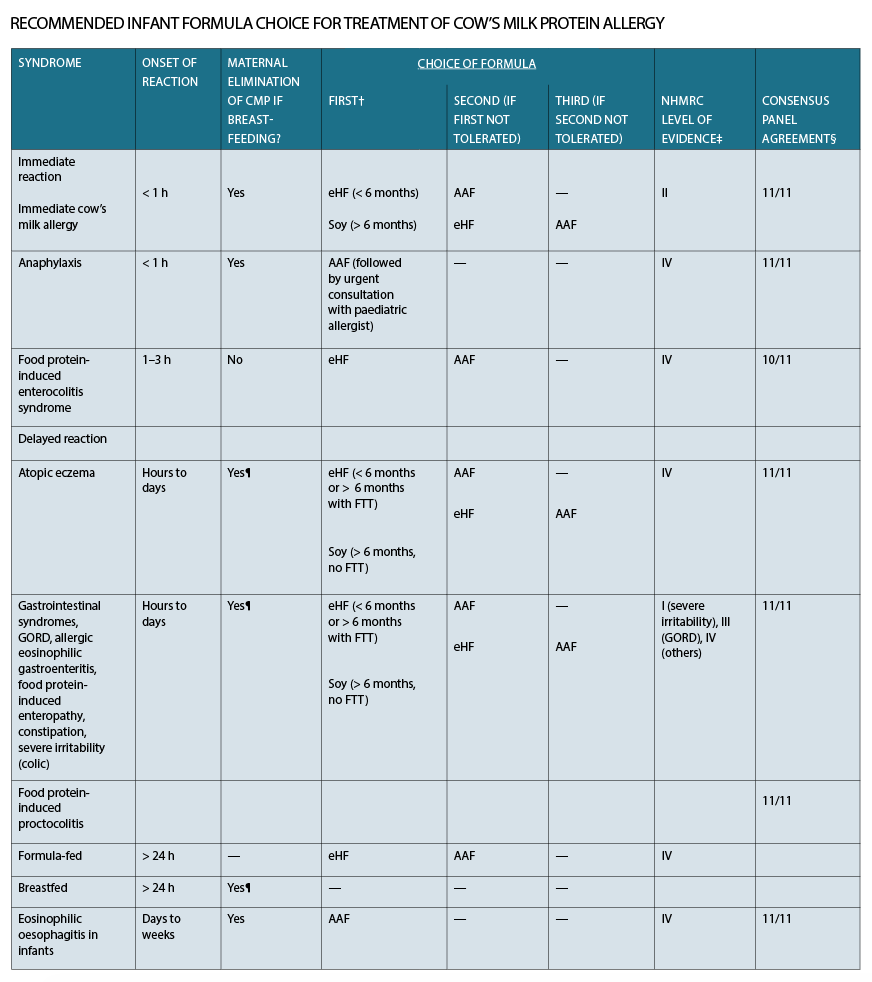

In the case of non-IgE mediated cow’s milk protein allergy syndromes, infants who are formula fed require a dairy replacement formula. The table overleaf recommends the stepwise progression of formula for the treatment of individual cow’s milk allergy syndromes.

In general, soy formula is first-line treatment, unless the infant is under six months old. If symptoms persist, extensively hydrolysed formula (eHF) (Peptijunior, Alfare) should be trialled. In 10-20% of infants with non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy, a third-line formula is required in the form of amino-acid based formula (AAF) (Neocate, Elecare). Prescription for eHF and AAF require specialist approval, although there is one over-the-counter extensively hydrolysed formula which also has added prebiotics in the form of lactose (Allerpro).

Food-protein-induced gastro-oesophageal reflux

Gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) commonly presents in infancy but can occur at any age. Infantile reflux is common and has been reported to occur in 25% of the general population in the first year of life.

GOR is the passage of gastric contents into the oesophagus with or without regurgitation and vomiting, lasting less than three minutes, in the postprandial period with few or no symptoms. It is the result of an abnormally functioning lower oesophageal sphincter which, in infants, is usually due to developmental immaturity of the lower oesophageal sphincter. Infantile GOR peaks at the age of four months and is usually resolved by 12 months. GOR is benign and does not impact on the child’s health. If symptoms of reflux persist beyond six months, or result in poor growth and failure to thrive, then simple steps to exclude food-protein induced GOR could be considered. The table on the next page outlines recommended formula management for allergen avoidance that can be used both in the process of diagnosis and treatment.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is considered when gastro-oesophageal reflux causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications, such as failure to thrive, haematemesis, refusal to eat, sleeping problems, chronic respiratory disorder, oesophagitis, stricture, anaemia and apnoea.

Complications of GORD are uncommon; however, it is important they are identified early and managed appropriately. Referral to a specialist may be required for formal investigations such as combined intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring, barium study and/or endoscopy and biopsy.

Eosinophilic Oesophagitis

Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) can present at any age although symptoms are somewhat age-dependent. Infants and young children typically present with food refusal, vomiting and failure to thrive while older children and adolescents may present with dysphagia, difficulty swallowing, choking and impaction.

It can be difficult to distinguish eosinophilic oesophagitis from GOR, and particularly in infants it is possible that it is under-recognised. In older children one of the most important symptoms to illicit is food sticking or difficulty swallowing. It is useful to enquire whether the child sits at the table longer than others, needs food finely chopped or pureed (particularly meat and bread) or requires water to wash down food or food gets stuck during meals. If these symptoms are present then referral to a gastroenterologist is required to diagnose eosinophilic oesophagitis endoscopically.

Protein-induced enteropathy

The clinical presentation of protein-induced enteropathy, which is most commonly due to cow’s milk, is similar to coeliac disease. This includes vomiting, diarrhoea, anaemia, failure to thrive and constipation. In severe cases enteropathy can result in protein-losing sequelae.

Most children with enteropathy present in the first year of life with non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms that can be associated with significant irritability. A careful history of newly introduced foods is important in order to illicit potential candidates for aggravating food allergens.

As for other non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy, cow’s milk is the predominant allergenic food with approximately 10 to 20% exhibiting symptoms of co-associated soy allergy/intolerance.

Since wheat is often introduced in the second six months of life as cow’s milk exposure (in the form of formula as complementary feeds, or as yoghurt or cheese) it can be difficult to tease out whether new onset gastrointestinal symptoms are triggered by coeliac disease or non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy.

Elimination/rechallenge sequences can be safely undertaken in the absence of red flags for referral. Referral to a gastroenterologist to consider endoscopic differential diagnosis should occur if one of the following is present: failure to thrive, iron deficiency anaemia, rectal bleeding or melaena or bilious vomiting.

So how do you distinguish cow’s milk enteropathy from lactose intolerance?

The diagnosis of non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy poses challenges as, apart from food elimination and re-challenge, no reliable diagnostic tests are available. There is clinical overlap with other food-associated disorders, such as lactose malabsorption, coeliac disease or idiosyncratic reactions to foods.

Management of cow’s milk allergy conditions in breastfed infants can be further complicated by incomplete cow’s milk elimination from breast milk, mainly due to maternal intake of unrecognised sources of cow’s milk protein.

Lactose intolerance can be distinguished from cow’s milk protein allergy either by eliciting a positive breath hydrogen test in an older child or in younger infants by assessing symptom resolution with stepwise removal of either lactose or cow’s milk protein from the infant’s diet in an elimination-rechallenge sequence. Lactose-free cow’s milk or formula can be used to assess whether lactose intolerance is independent of cow’s milk protein allergy.

Alternatively, infants who remain symptomatic on lactose-free milk, but settle on soy formula, (which has neither lactose nor cow’s milk protein) are most likely to have cow’s milk protein allergy.

Food-protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome

Food-protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) has a pathognomic clinical presentation with profuse vomiting in an infant in the first year of life, usually one to four hours after the first or second exposure to a food not previously tolerated.

FPIES is often mistaken as sepsis, acute viral gastroenteritis or surgical conditions such as malrotation or intussusception in a young infant. There are no useful diagnostic tests for FPIES, and the diagnosis relies on recognition of clinical features.

The following diagnostic criteria have been proposed:

(1) Repetitive vomiting and/or diarrhoea within one to four hours of ingestion (following ?rst exposure to a food) without other identi?able cause.

(2) Symptoms limited to gastrointestinal tract.

(3) Complete resolution of symptoms on avoidance.

(4) Recurrence of symptoms upon challenge. Referral to an allergy specialist for assessment of suspected FPIES is appropriate for this uncommon condition.

Protein-induced proctocolitis

Protein-induced proctocolitis is characterised by blood in the stool of an infant who is well, typically breastfed and thriving. It is important to rule out constipation and rectal fissure (in the latter, blood is usually on the outside of stool which is more formed).

Elimination of cow’s milk and sometimes soy from the infant’s diet results in resolution in the majority of cases.

If the child is failing to thrive or has not responded to simple cow’s and soy milk elimination from both the mother and infant’s diet, then referral to an allergist or gastroenterologist is recommended.

The majority of infants with allergic proctocolitis develop tolerance to cow’s milk by 12 months and careful reintroduction to cow’s milk should occur at that time to assess whether the condition persists.

Constipation/ colic

Controversy remains about whether cow’s milk allergy can cause constipation and again cow’s milk and soy appear to be the main potential culprits. Research is divided about whether the phenomenon exists and if it does, how common it is.

Certainly, there is clinical evidence that some cases of constipation resolve upon cow’s milk removal from the diet for two to four weeks with recurrence of symptoms upon rechallenge.

Cases with symptoms of formula intolerance or constipation from early in infancy are more likely to respond to cow’s milk elimination than those with late onset symptoms of constipation which are unlikely to be cow’s milk allergy related.

Colic is defined as a condition in a healthy baby in which there are periods of intense, unexplained fussing/crying lasting more than three hours a day, more than three days a week for more than three weeks.

Its onset is usually around two to four weeks and it has usually resolved by about four months of age. Most children with colic do not have cow’s milk allergy and most cases resolve spontaneously without any medical help.

Some parents describe concern that their child is in pain with drawing up of the legs. Although some of these cases are due to cow’s milk allergy, sometimes air swallowing from excessive crying can result in similar drawing up of the legs with evidence of discomfort.

If a baby has new onset symptoms when introduced to cow’s milk formula then a cow’s milk allergy should be considered and elimination/rechallenge sequence undertaken, emphasising to the family that cow’s milk allergy is not confirmed until symptoms have been elicited on rechallenge.

Conclusions

Non-IgE mediated cow’s milk allergy remains a complex area of diagnosis and management and further research is urgently needed to progress the field. Improved diagnostic tools would add significant value to the field as would longitudinal studies to assess natural history and prognosis.

Involving dieticians in management of allergen avoidance, and to ensure optimal nutrition is maintained, is essential.

Professor Katrina J Allen is Paediatric Gastroenterologist/Allergist at Centre of Food and Allergy Research, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Department of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the University of Melbourne Department of Paediatrics all at the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, and University of Manchester, UK

Email: Katie.allen@rch.org.au

Online resources:

1. World Allergy Organisation http://www.worldallergy.org/

2. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA) http://allergy.org.au/about-ascia#sthash.neLbZPvW.dpuf http://allergy.org.au/

3. Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne website, Practical tips for parents

4. Raising Children’s Network website

References:

1. Kemp AS, Hill DJ, Allen KJ, Anderson K, Davidson GP, Day AS, Heine RG, Peake JE, Prescott SL, Shugg B, Sinn JKH. Guidelines for the use of Infant formulae for the treatment of Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy: an Australian consensus panel opinion. Medical Journal of Australia 188 (2): 109-112, 2008.

2. Allen KJ, Davidson GP, Day AS, Hill DJ, Kemp AS, Peake JE, Prescott SL, Shugg A, Sinn JK, Heine RG. Management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants and young children: an expert panel perspective. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 45 (9): 481-6, 2009

3. Allen KJ, Martin PE. Clinical aspects of pediatric cow’s milk allergy and failed oral immune tolerance. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 44 (6): 391-401, 2010

4. Allen KJ and Heine R. Eosinophilic Esophagitis – trials and tribulations. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 45(7): 574-82, 2011

5. Allen KJ. The vomiting child: what to do and when to consult. Australian Family Physician 36(9); 684-7, 2007

6. Nowak-W?grzyn A. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome and allergic proctocolitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015 May-Jun;36(3):172-84

7. Nowak-W?grzyn A, Katz Y, Mehr SS, Koletzko S. Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 May;135(5):1114-24.