Simple economics dictates that more GPs will need to take on the management of gout in their patients. But that won't necessarily be easy. [SPONSORED]

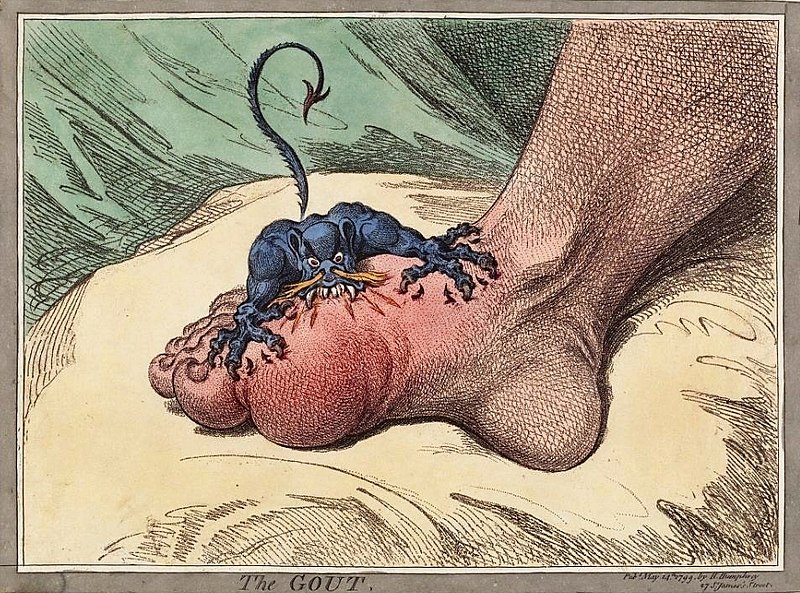

“Gout is a malady fairly entitled to boast of its great antiquity, for it was probably one of the earliest diseases to which the flesh became heir when man began to participate in the luxuries of civilised life. It is a disease, also, which can lay claim to having had among its victims of the most renowned of the human race, from their position, opulence, and intellect.”

– Alfred Baring Garrod, The Nature and Treatment of Gout and Rheumatic Gout, 1859

Centuries of believed wisdom, some of it medical wisdom, is hard to kick.

As far as most of the patient community is concerned, there are two things they generally think they understand about gout: you get it if you drink too much and eat rich foods (i.e., you’re a bit of an overindulgent slosh), and it’s on the decrease over time, as modern medicine and healthier habits of more responsible sufferers take hold. Both beliefs are wrong, of course.

The situation isn’t helped by the popular media. A recent review of 114 articles in British and American newspapers found gout was still depicted regularly as a “self-inflicted condition that is socially embarrassing and the focus of humour.”1

The authors concluded: “Initiatives that challenge popular perceptions of gout may play an important role in changing public understanding about the disease, ultimately increasing the update of effective urate-lowering therapy and reducing reliance on unproven strategies.”

Low achievement of allopurinol prescribing and serum urate testing in Australia suggests that GPs struggle to manage gout in the general population.2

According to Associate Professor Philip Robinson, from the University of Queensland, in an ideal world, most gout patients should probably be cared for by a rheumatoiogist, but the concept is economically unrealistic. GPs should be involved a lot more in the management of gout than they are, he says, but “educating GPs is a tough gig”.

“They have thousands of diseases they have to be across and [getting them] to take note of the complexities of a disease that people think isn’t important, and is potentially self-inflicted is essentially impossible.”

Professor Robinson says that most, except a small group who are across the literature, still believe diet is very important. “This reflects the system of medical education, that when no evidence exists then people take a best guess and teach it as gospel. It then takes a lot to change long held, but incorrect information … especially when there is partial truth to it.

“While a strict diet can decrease serum urate by a small amount, in reality it does not produce a big enough effect to make a clinically meaningful difference in the majority of gout patients.”

A key message for suspected gout sufferers is that genetics is probably the largest contributor to the condition.

The condition revolves around the physiology of uric acid/urate. Although urate is introduced to the body by diet, is produced by metabolism, and how your effectively you metabolise uric acid is, in large part, determined by your genes.

Most of the genes that are associated with serum uric acid levels or gout are involved in the renal urate-transport system.

And, of the four control mechanisms for serum urate, three are primarily influenced by the patients’ genetics.3

Says Professor Robinson: “Patients clearly can’t control their genetics, so understanding [the role of genetics] is important for patients, so they realise they were probably always going to get gout, regardless of their diet.”

Other factors that can cause high uric acid levels include medications such diuretics and immune suppressing drugs, vitamins such as niacin, and conditions such as hypothyroidism, obesity, psoriasis and renal insufficiency.

Professor Robinson emphasises that while you can identify certain foods for gout patients to avoid during treatment, the cornerstone of effective gout treatment is managing serum urate levels downwards to below target, mainly through the use of allipurinol.

In essence, gout is a crystal deposition disease. The pathophysiological mechanism leading to the crystal formation can be reversed by reducing serum urate levels to below the threshold of saturation where the crystals form.4

Treating to target isn’t entirely straightforward, though. Targets for patients can vary depending on things such as whether the patient has tophi or not. In addition, you can run into complications around flares as you start managing urate downwards.

The recommended target for patients with gout and no tophi is 0.36mmol/L and for those with tophi is is 0.3mmol/L.

Urate-lowering therapy will often cause flares.

According to Professor Robinson, an axiom that is common with doctors and patients during urate lowering therapy is that if the flare becomes acute, the therapy should be stopped. But Professor Robinson believes there is no basis for following this path.

“What ends up happening is that patients often have numerous flares and never end up on any urate-lowering therapy”, he says, adding that this will often make the overall gout problem much worse.

“I say to my patients, you should only stop your urate-lowering medicine the day before you die.”

The most common first-line preventative agent is allopurinol, a purine xanthine oxidase (XO) inhibitor which has been available since the 1960s.

The biggest change to the use of this agent in the last five years has been a recommendation that treatment start at low doses and be increased slowly to allow the body’s immune system to become tolerant and avoid potential complications, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome.2 The other agent used in the last decade, mainly when the symptoms are advanced and chronic, including tophus formation, has been febuxostat, a purine base analogue xanthine oxidase inhibitor.

Until recently, febuxostat was considered as the most effective agent to lower uric acid levels where there has been a diagnosis of chronic gout.5

However, a US study of 6190 patients, reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in March this year, looking at the relative outcomes of treating with allipurinol or febuxostat in patients with gout and cardiovascular diseases, suggests that while the overall risk of an adverse cardiac event is the same for both agents, there may exist a heightened risk of cardiovascular death using febuxostat over allopurinol.5

The study underlines that gout treatment is often complicated as the patients usually have a number of co-morbidities, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension and ischaemic heart disease.

The upshot of this is that if you are identifying gout for the first time, it is very important to screen for, and address, these other potential issues with your patients.

This feature was written for The Medical Republic based on funding provided via an educational grant from by A.Menarini Australia Pty Ltd.

References:

1. Duyck S et al, Arthritis Care and Research 2016; 68:1721-5

2. Robinson, P, et al, JReum, 2015, 42:9

3. Robinson, P, Rheumatology Republic, April 2018, 18-19

4. Fernando Perez-Ruiz, et al, Rheumatology, 57, Jan 2018, i20-i26

5. Vasvinder AS, et al, Athritis Res Ther, 2015:17(1): 120

6. White, WB, et al, N Eng J Med, 2018, 378:1200-1210