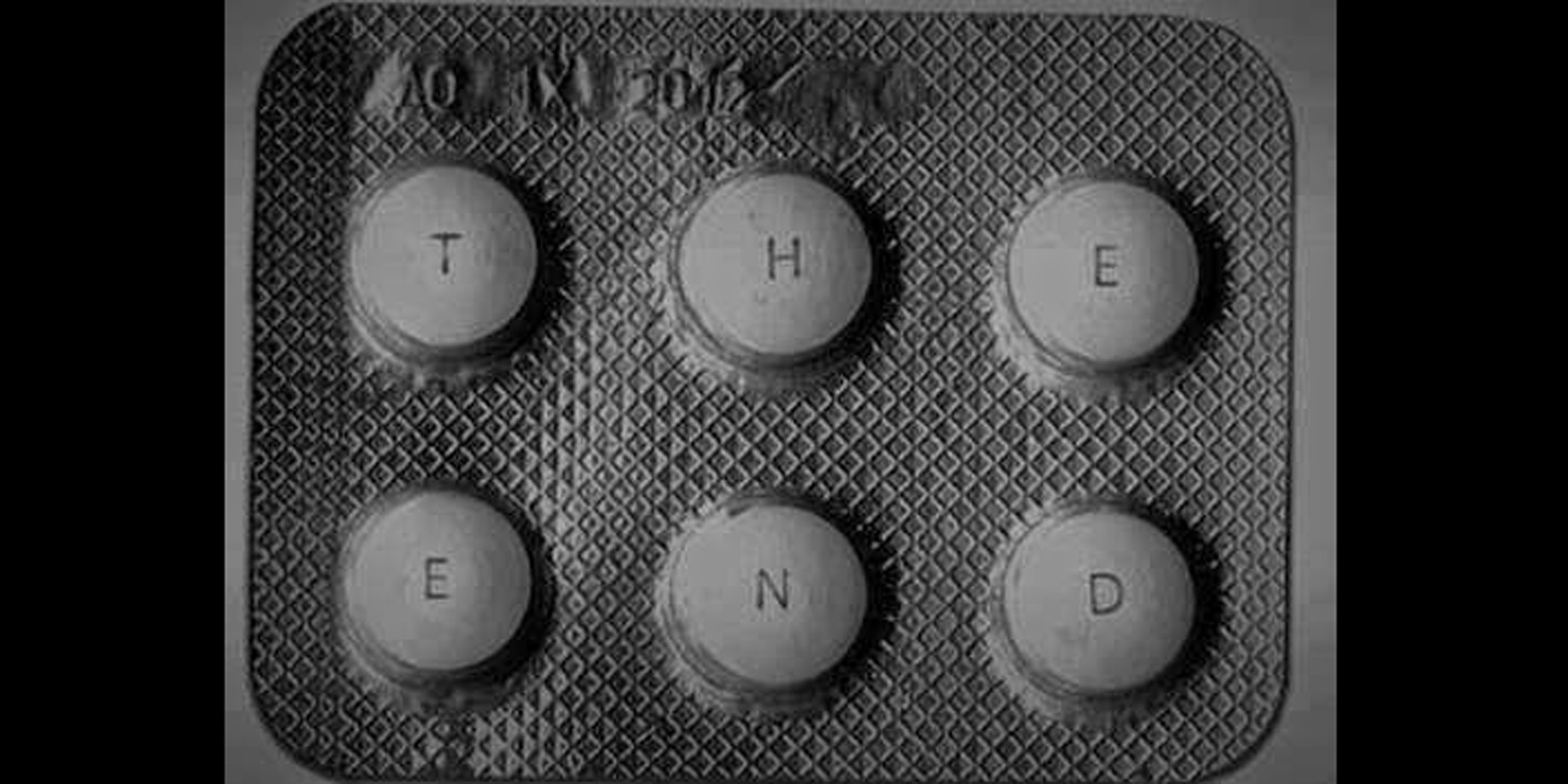

Medicine leaflets overemphasise side effects and fail to inform patients about the benefits of drugs

Patients often walk away from a pharmacy with either no information about the medicines they have just been dispensed, or a with leaflet containing a long list of scary side effects.

A report released by The Academy of Medical Sciences in the UK this month, proposes that medicine leaflets are detrimental to good health, turning patients off their medications by highlighting the potential adverse effects and failing to inform them about the benefits of drugs.

Balance should be restored, with a more even appraisal of the medicine’s potential benefits and risks.

Specifically, the report suggested absolute risk figures replace qualitative terms, such as “low risk”.

It also recommended that both positive and negative framing be used for statistics about risk.

Similar changes were long overdue in Australia, said Adjunct Professor David Sless, director of the Communication Research Institute at ANU.

Professor Sless led the original development of usability guidelines for consumer medicine information (CMI) leaflets in Australia in the early 1990s.

There had been almost no progress since leaflets were first developed, which was outrageous, he said.

“The balance of benefits as opposed to side effects should have been there right from the start,” he said. But placing emphasis on the benefits was seen as a form of direct-to-consumer advertising at the time.

The difficulty was providing balanced information without overwhelming the reader, according to Mark Metherell, a spokesman for the Consumer Health Forum of Australia.

“Leaflets can become too long and unwieldy very easily, requiring text in tiny print which people are less likely to read,” he said.

As it was, patients often did not even receive a CMI when purchasing a prescription medication in Australia, Professor Sless said.

While information was available on the TGA’s website, manufacturers were no longer putting leaflets inside medicine packaging because of concerns about keeping the information up to date, Mr Metherell said.

The Review of Pharmacy Remuneration and Regulation interim report, released this month, called on pharmacists to routinely hand CMI leaflets to patients, in accordance with Pharmaceutical Society of Australia guidelines.

Prescribers need to indicate when the provision of a CMI should be mandatory, the review recommended.

“Consumers are not always aware of the availability of a CMI or, indeed, being offered a CMI as part of the dispensing process,” the report said.

Professor Sless said he would be delighted if pharmacists adopted this practice, but it was unlikely largely because of the risk of the CMI affecting compliance.

He said there was a “lingering and residual disgruntlement” towards CMIs among pharmacists.

Pharmacists’ long-held concern had been that the side effects listed in the document would turn patients off using the product, Professor Sless said. GPs were similarly hesitant to print out CMIs.

In addition to including more balanced information, simple measures to improve patient access to CMI could include putting a web address for CMIs on the back of drug packaging, or re-introducing CMI leaflets inside products, he said.