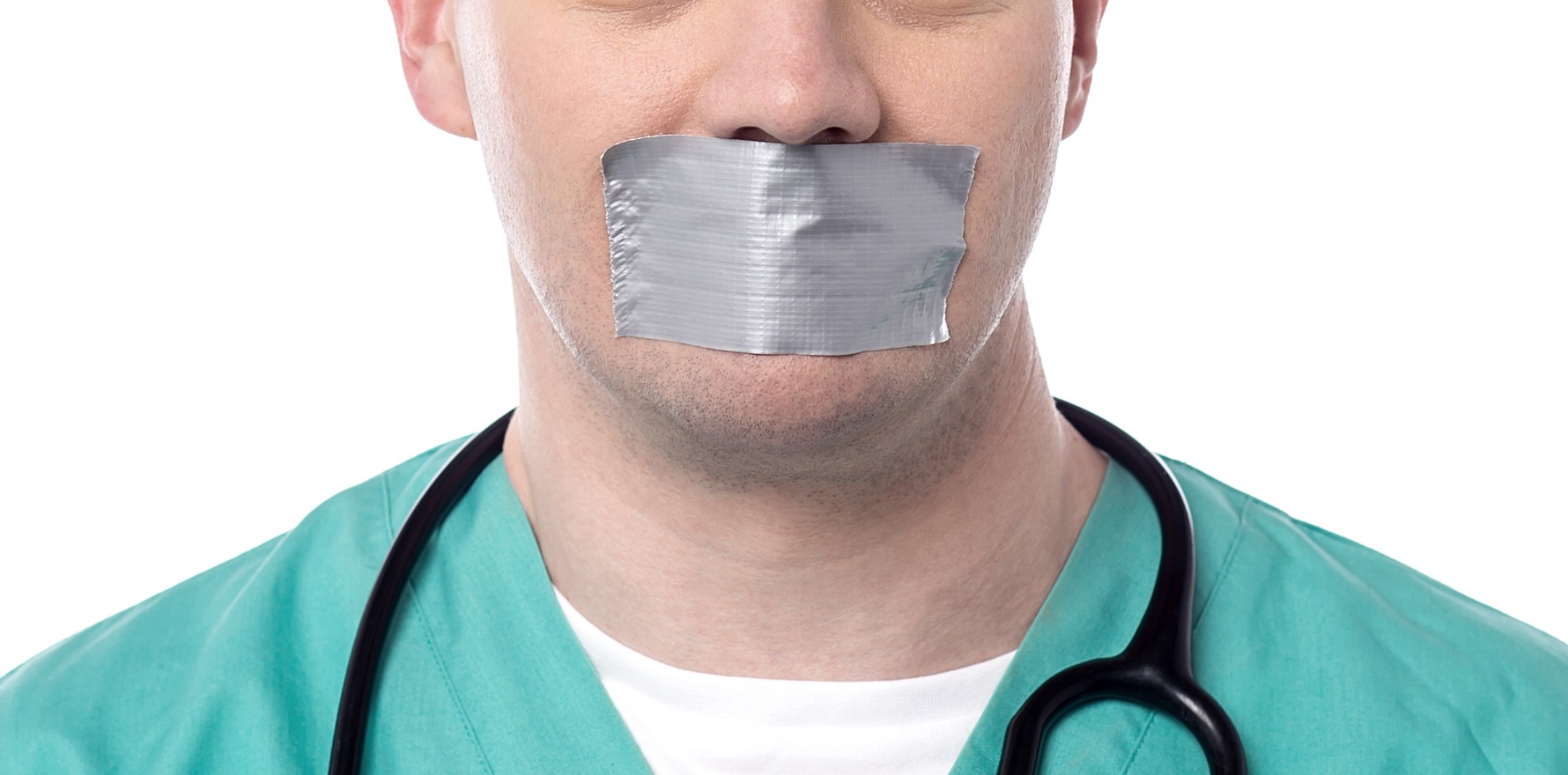

A medical degree now costs you your right to free speech and makes you accountable for your profession’s reputation 24/7.

Handwashing, as a way of reducing the spread of infection, has gained new traction in 2020.

It is worth remembering that this concept was not always accepted. In fact, when first proposed as a way to reduce puerperal infection and maternal mortality it was rejected by the medical authorities of the time.

Ignaz Semmelweis observed that women who delivered in one division of the hospital had a higher infection and mortality rate than those in another.

The only observable difference was that puerperal infections were higher where medical students rather than midwives were involved. Ultimately, he concluded that the medical students were going from the dissecting room to the maternity room and transporting the infection from mothers who had died from the disease to healthy ones. Mortality rates dropped from 18% to 1.27% where his orders to wash hands was followed, in 1848.

Semmelweis found that obstacles to his work were erected. By 1865, when he died, his teaching was still rejected by the medical establishment.

One might ask why?

Perhaps there was a view that he would bring the profession into disrepute or undermine “the reputation of the profession”.

This couldn’t happen today. Surely, we know better now. We understand the need to question current assumptions and not assume that medical science is “settled”. We know that the only way this happens is for conventional practice to be questioned – both in private and public.

Sadly, this is not the case and medical authorities have learned nothing in over 150 years.

The new AHPRA code of conduct, which takes effect on 1 October, states that “The boundary between a doctor’s personal and public profile can be blurred” and “As a doctor, you need to consider the effect of your public comments and actions outside work, including online, related to medical and clinical issues, and how they reflect on your role as a doctor and on the reputation of the profession.”

This sounds benign, but is not. This is 1984 doublespeak stuff. You start out as a citizen, but once you have a medical degree rather than a legal one, or perhaps an electrician licence, your work is no longer a component of who you are but defines you.

When you leave work, you are no longer a citizen, you are still a doctor. So much for needing down time – you now work 24/7.

Any questioning of current conventional thinking may leave you accused of not considering the “reputation of the profession”. You may be hauled in front of the inquisitors.

Any modern-day Semmelweis could meet the same fate as the original. His questioning the practice of doctors had the potential to affect the “reputation of the profession”.

But surely regulations will be applied sensibly?

History shows the regulator adopts a heavy-handed approach. Witness the case of Gary Fettke. One wonders what drove complaints against the late Dr Yen-Yung Yap, found deceased on September 5.

Cancel culture lives on in medicine. Sadly, some applaud this, believing that silencing dissent is easier than having their beliefs challenged.

Let me be clear. False defamatory comments should not be made. We don’t need open season on everything. However, the concept of scientific inquiry is not that what we believe is right and needs verification, but what we believe is wrong and must be proven correct.

As Albert Einstein said: “No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right; a single experiment can prove me wrong.”

If we are unable to start from the premise that we may be wrong, we can never advance our knowledge.

The RACGP and ACRRM both have new presidents. They must defend our ability to be questioning. Giving up free speech is not the price of a medical degree.

As an aside, also on the agenda for both presidents should be a meeting with the Pharmacy Guild to learn how to represent members’ interests. This means more than just asking government for more money – which it won’t have. It means getting outcomes which improve the lot of members.

Maybe even ask members what matters to them.

There is an old adage that the more things change, the more they stay the same. When our approach to innovation and questioning of what we do is the same in 2020 as it was in 1848, it is nothing to enshrine.

Dr Joe Kosterich is a GP based in Perth, Western Australia. To read more, go to www.drjoetoday.com