A look at the role of GPs in identifying and supporting adult patients who may benefit from, or already have, a cochlear implant.

Cochlear implants have revolutionised the management of sensorineural hearing loss for more than 40 years.

Australia has been at the forefront of both cochlear implant technology and universal newborn hearing screening programs. The indications for cochlear implantation have been continuously broadening since the world’s first multichannel device was implanted by Professor Graeme Clark in Melbourne in 1978 for a patient with profound sensorineural hearing loss.

The prevalence of hearing impairment in Australia has been predicted to increase substantially from 2005 to 2050, with an estimated 2.6 million Australians suffering from moderate-or-worse hearing loss in their better hearing ear.

This article focuses on the role of general practitioners in identifying and supporting adult patients who may benefit from, or already have, a cochlear implant.

What is a cochlear implant?

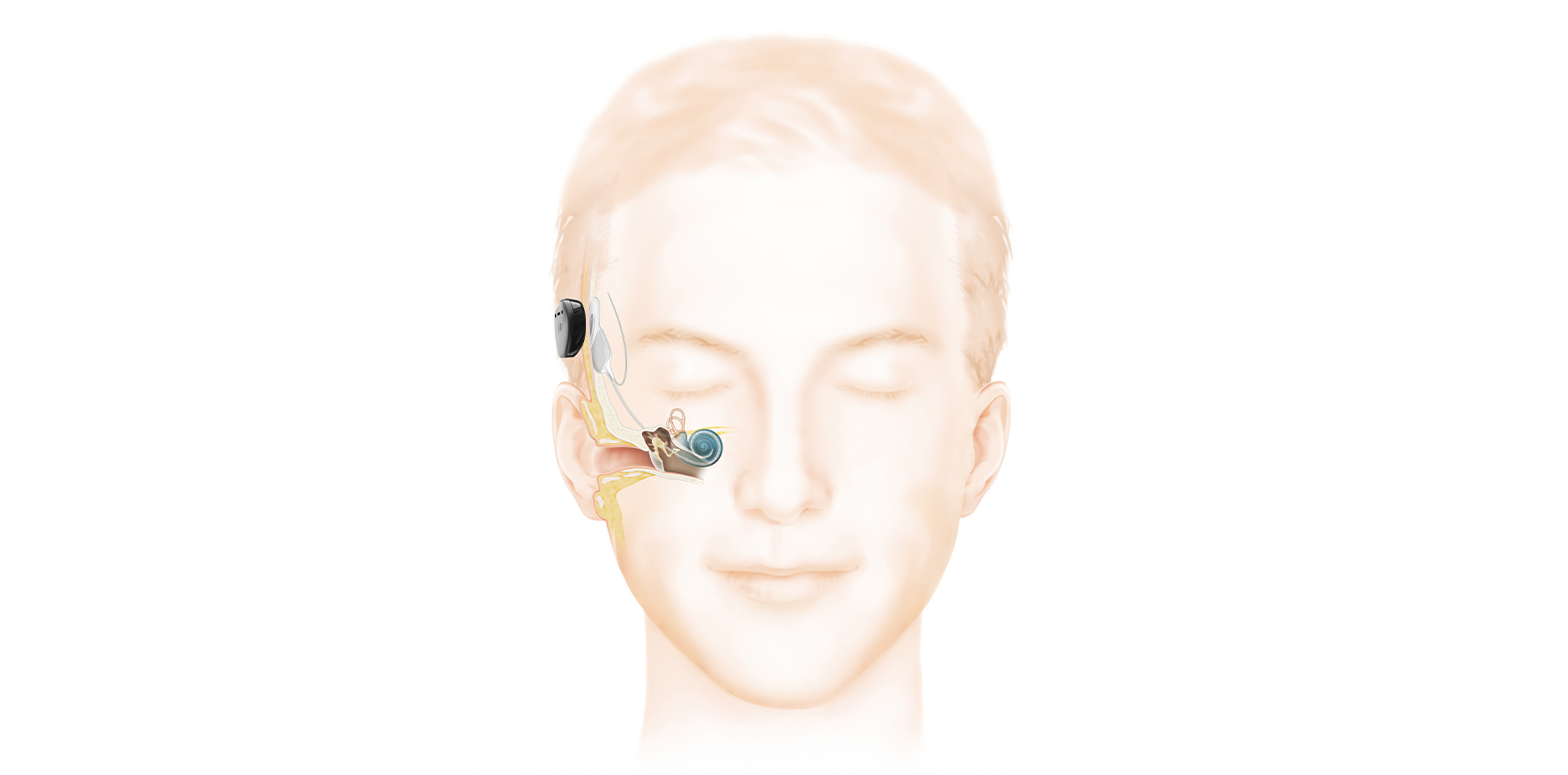

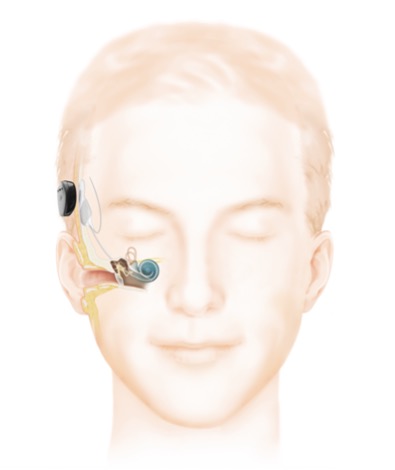

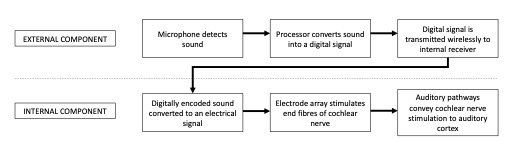

A cochlear implant is a surgically implanted hearing device that rehabilitates sensorineural hearing loss by direct electrical stimulation of the cochlear nerve (Fig 1).

There are two components: the internal, surgically implanted device and an externally worn sound processor. The two components are magnetically coupled and communicate wirelessly through the skin.

Like a traditional hearing aid, the external sound processor can be removed when not required and is responsible for detection of sound waves via a microphone. The internal component of the cochlear implant replaces the function of cochlear hair cells by direct electrical stimulation of the spiral ganglion neurons.

Indications for cochlear implantation

Annual routine screening for hearing loss in people 65 years or older is recommended and also a legal requirement for some occupations (e.g., commercial drivers).

The increased effort of listening, social disengagement and lack of central stimulation with age-related hearing loss has been identified as a risk factor for dementia. Patients may openly express frustration with their hearing aids and acknowledge their increasing difficulty in communication during their consultation.

Alternatively, it may be noted that a patient is heavily reliant on visual clues and context, with careful questioning needed to divulge the impact of hearing impairment on their quality of life (Table 1).

| Do you struggle to hear in background noise (e.g., restaurants, social occasions)? |

| Do you struggle to hear people regularly on the telephone? |

| Do you often ask people to repeat themselves? (Difficulty with children, high-pitched voices or “mumblers” are common). |

| Do you avoid social situations because of your hearing difficulties? |

| Have your relatives or friends suggested you seek help for your hearing difficulty? |

Ongoing hearing impairment despite hearing aid usage can be due to audiological issues (e.g., inadequate amplification, feedback, poor fitting mould) or lack of usage for non-audiological reasons (e.g., recurrent acute otitis externa, cosmetic concerns). As a rule of thumb, patients should have their hearing aids adjusted annually to their current hearing needs and replaced/updated every five years.

Audiologically, patients with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, a pure tone average worse than 60db and speech discrimination worse than 60%, would benefit from formal audiological cochlear implant assessment (ACIA).

Other less common configurations, such as single-sided deafness and isolated high frequency sensorineural hearing loss, can also be potentially rehabilitated with cochlear implantation (Table 2).

Patients may also have their local (non-hearing implant) audiologist recognise that they have reached the limit of hearing aid rehabilitation and suggest specialist review.

| Clinical criteria: does not benefit from well-fitted, recently adjusted hearing aids |

| Audiological criteria: Screening “60/60 rule” for bilateral loss: – unaided pure-tone averages (average of the threshold at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz) worse than 60dB, AND – unaided monosyllabic word recognition score <60% |

| Special cases: – Severe-to-profound single-sided deafness ± troublesome tinnitus – “Ski-slope” hearing loss – preserved lower frequency hearing with severe-to-profound high-tone sensorineural hearing loss and poor speech discrimination (<60%) |

The exact criteria for cochlear implants are constantly evolving as research examines the audiological and quality-of-life outcomes. ACIA is an audiological battery of tests that attempts to determine a person’s real-world hearing capabilities and is performed by an audiology team with experience in cochlear implantation.

Traditional audiology includes a pure-tone audiogram, tympanometry and standard word-recognition scores. ACIA involves additional testing of more complex audiological tasks such as sentence recognition, in quiet and noise, with appropriate amplification (i.e., hearing aids worn). The ACIA aims to identify patients that will have better hearing with a cochlear implant than traditional hearing aids.

In general, a motivated patient with recent onset of profound deafness, poor speech discrimination and normal anatomy will achieve excellent outcomes with cochlear implantation (e.g., presbycusis with longstanding hearing aid usage).

Anatomical abnormalities, surgical complications (e.g., electrode misplacement), cochlear fibrosis, longstanding auditory deprivation and prelingual onset of deafness have all been associated with poorer cochlear implant outcomes in the adult patient.

Workup – a typical patient journey

Once a patient has been identified as a potential cochlear implant candidate, they are assessed by their hearing implant surgeon and audiologist in close collaboration.

The pre-implant assessment confirms implant candidacy and that there are no contraindications to implantation (Table 3). Typically, this includes a thorough otological history and examination; CT scan of the petrous temporal bone; MRI of the internal auditory meatus; objective vestibular function testing; validated quality-of-life questionnaires and personalised goal setting (e.g., SSQ 26, COSI). Patients undergo careful counselling and are often encouraged to meet prior cochlear implant recipients.

Multiple factors contribute to the decision of which cochlear implant brand, electrode array and side to implant.

| Not fit for surgery in general (there is no upper age limit on cochlear implantation) |

| Anatomically unsuitable for implantation: – Complete cochlear ossification (e.g., post meningitis) – Absent cochlear or cochlear nerve (e.g., congenital abnormality) |

| Active middle-ear disease (e.g., cholesteatoma, perforation) |

| Unwilling or unable to have audiological follow-up |

Surgery is done under general anaesthetic via a post-auricular approach and takes 1-2 hours. The implant is tested intraoperatively after insertion to confirm it is functioning normally and to provide initial electrical stimulation parameters. Patients can have their head bandage removed, cochlear implant activated and be discharged from hospital day 1 post-surgery. Initial surgical and audiological follow-up occurs within the first 2-3 weeks. Note that many units attach the external sound processor and activate the implant only at this later stage.

Patients have frequent sessions for cochlear implant mapping (adjustment of electrical stimulation) post-operatively in conjunction with their audiologist, who also prescribes listening exercises to maximise hearing improvement.

Cochlear implant recipients are seen at decreasing frequency over time as their hearing pathways adjust to this new method of hearing and their hearing performance stabilises. The use of remote telehealth mapping of cochlear implants has increased during the current pandemic and will probably remain an important tool for our regional and remote patients.

Special considerations in the cochlear implant patient

All patients are issued with a Patient Identification Card to identify their exact implant model/make.

Cochlear implants are not a contraindication to MRI scanning despite the internal magnet, but it is important the radiology practice is aware of the cochlear implant prior to imaging. Depending on the implant, minimal precautions, head bandaging or magnet removal may be required for scanning. The device will obscure imaging of adjacent intracranial structures, but this artefact can be reduced by magnet removal.

There is an increased risk of pneumococcal meningitis with cochlear implantation due to the potential communication of the middle ear with the cerebrospinal fluid. As such, cochlear implant recipients are eligible for funded doses of 13vPCV and 23vPPV under the National Immunisation Program (NIP). Some implant units also recommend the quadrivalent and meningococcal B vaccinations.

Evidence of post-auricular infection, skin breakdown or significant trauma in an implanted ear necessitates urgent specialist review for management. Likewise, episodes of acute otitis media should be managed in conjunction with the implant surgeon, as “watchful waiting” without antimicrobial therapy is inappropriate for the child with a cochlear implant.

Application of electrical current to the head/neck (e.g., monopolar diathermy, electroconvulsive therapy) should be avoided with a cochlear implant in situ. Patients should also be aware that the internal components may activate metal detection devices (e.g., airport security).

Future directions

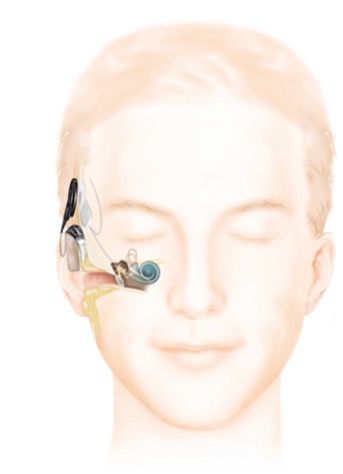

Cochlear implant design is constantly advancing with the aim to improve performance, residual hearing preservation rates, MRI compatibility and quality of life for patients. Current implants provide a variety of cosmetic options including behind-the-ear and off-the-ear sound processors (Fig 2). Increased connectivity with other devices (e.g., mobile phones, contralateral hearing aids), water-proofing and longer battery life continue to improve the cochlear implant experience for patients.

New advances being researched include totally implantable, drug-eluting or piezoelectric/light stimulating cochlear implants. Future cochlear implants could offer the possibility of continuous, invisible and more natural-sounding hearing rehabilitation.

Hearing in background noise and music appreciation both remain difficult tasks for the current CI recipient. While cochlear implants have been the most widely utilised neuroprosthesis to date, they currently cannot outperform the healthy hearing ear.

Timothy James Matthews FRACS (ORL-HNS), MBBS (Hons), BSc (Bioinformatics) is a neurotologist and hearing implant surgeon at St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney and conjoint lecturer at the University of New South Wales.