People are looking for guidance on how to process negative feelings triggered by ecoanxiety

“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo. “So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

– J.R.R. Tolkien

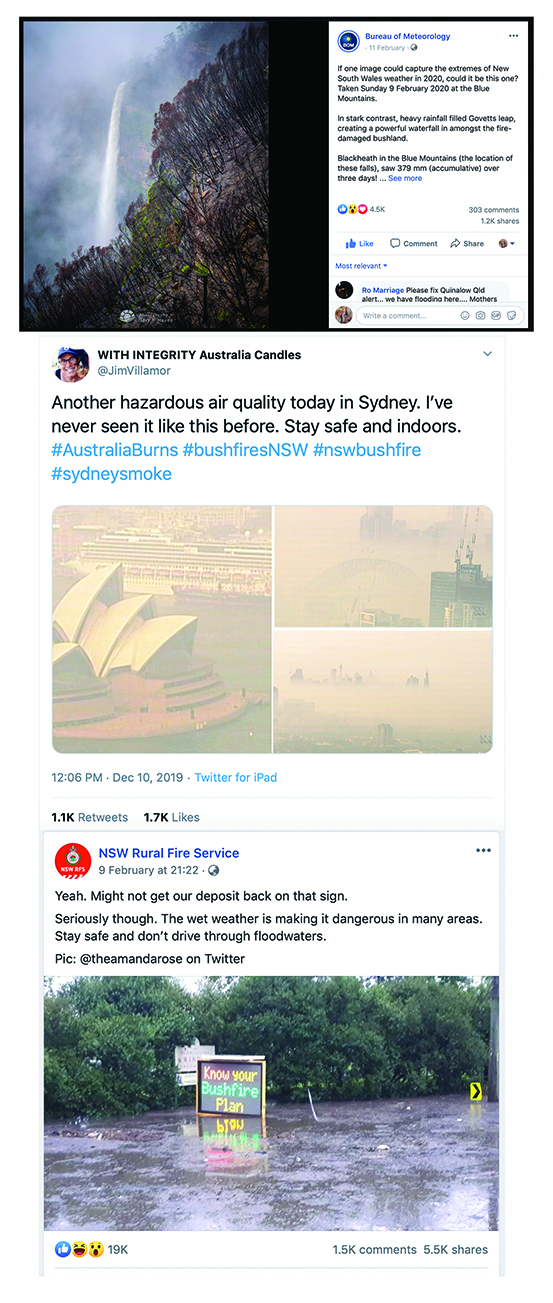

Thinking back on the summer we’ve just had here in Sydney it feels like something has snapped.

The far-off threat of climate change that scientists had been warning us about for decades was suddenly on our doorsteps.

The bush became a fire-breathing dragon. Smoke wiped out the city skyline. Blue skies were snatched away. On a few days, it literally rained ash.

Bewildered, people snapped photos of the funny orange dot in the sky – “the new normal” for post-apocalyptic Australia.

As air pollution hit 11 times safe levels, North Sydney pool put up a warning sign telling people that exercising outside could be bad for their health.

Between December and February, one disaster rolled into another, almost to the point of ludicrousness. Hailstorms and dust storms struck NSW weeks apart. Floods doused previously uncontrollable fires.

It was a disorientating start to the decade.

But there was a feeling of hope over the summer, too.

Tens of thousands turned out for the climate change rally at Sydney Town Hall on 10 January. “We can’t breathe”, “What hope is there for my unborn child?”, “Stop upsetting David Attenborough” the protest signs read.

On 31 January, among the blue lasers, bad dancing, and booze of a mosh pit in Sydney’s west, the words of 17-year old environmental activist Greta Thunberg cried out. Mashed with DJ Fat Boy Slim’s hit song “Right here, Right now” was the war cry:

“The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And, if you choose to fail us, I say we will never forgive you. We will not let you get away with this. Right here, right now is where we draw the line. The world is waking up. And change is coming, whether you like it or not.”

For the first time that night, hundreds of people reached for their phones to record and broadcast the generation-defining message.

Why should such feelings about climate change – which are echoed a million times over on social media – matter to the readers of a GP magazine?

Good question! It doesn’t feel like a health issue per se.

Those traumatised by climate change-related disasters obviously need to be offered mental health support, but the rest of us are just feeling a bit down, stressed or hopeless – which is, surely, a rational and proportional response to the unfolding reality rather than a medical issue.

But when I put out a call to experts on the topic of “ecoanxiety”, the response was overwhelming.

Many psychologists and GPs are deeply concerned about the negative effects of inaction on climate change on the population’s mood.

Not because ecoanxiety needs to be diagnosed and treated (most were against the medicalisation, except in rare cases), but because people need emotional support when they’re going through a difficult moment in history.

The sheer number of people affected by the recent disasters in Australia is stunning. If the recent poll of 3,000 Australians by ANU is anything to go by, 80% were directly or indirectly affected by the bushfires and around half felt anxious or worried.

People are looking for guidance on how to process these feelings in a healthy way.

BIG PICTURE THINKING

One of the groups that you’d expect to be feeling the strongest ecoanxiety are climate scientists. They are confronted by the data all day, every day. They know exactly how dangerous the current situation is for our planet.

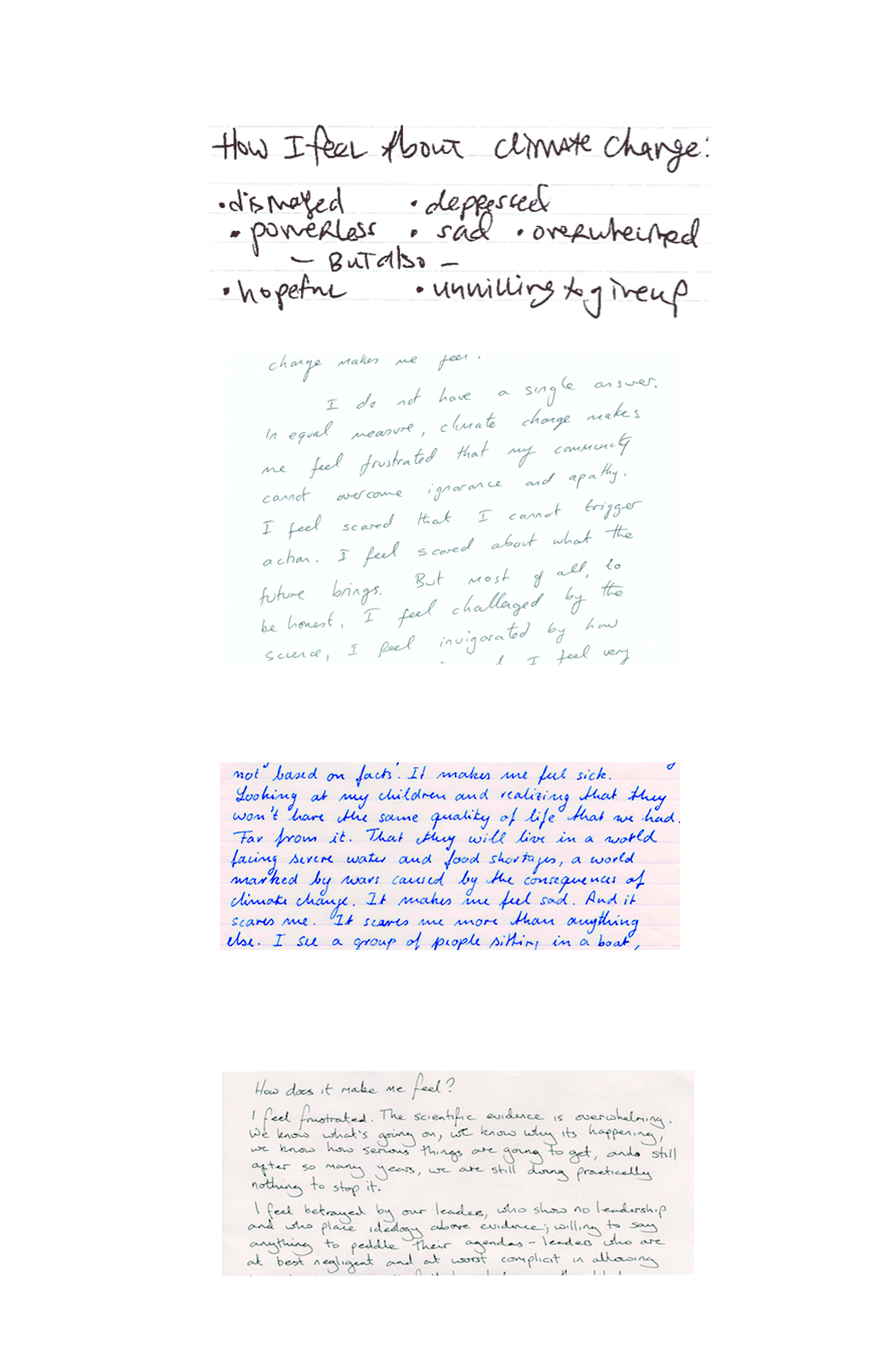

In 2015, Canberra-based science communicator Joe Duggan asked climate scientists around the world to share their feelings.

When you read their handwritten letters, they are ink-stained with words such as anger, guilt, frustration, powerless, worry, sad, upset, bewildered, distressed and depressed.

Duggan says his “Is this how you feel?” project was cathartic not just for the scientists, but also for everyday people who could “see their feelings mirrored in the letters of the scientists”. He’s taking new submissions from climate scientists this year to see if the mood has shifted.

Professor Lesley Hughes, one of the letter writers who has been at the forefront of climate change science in Australia for decades, isn’t immune to the personal downsides of her profession.

“It does make me anxious,” she says. “I worry about the future of my children and unborn grandchildren a lot.

“But look, if you’re totally anxious all the time, you’re also useless. I also think for me to be effective as a scientist and an advocate and just as an everyday human being going about my life, I actually have to corral those thoughts quite closely, put a big brick wall around them and act as if there is hope for the future.

“Hope is a strategy as much as it is an emotion, and if you don’t have that will then you give up and, of course, if you give up, we are really screwed.”

Professor Hughes first started working in climate change science in the 1990s, long before the explosion of research in the field. Since then, she has served on the Climate Commission and the Climate Council of Australia.

“When you’re a person that spends much of their professional life and possibly quite a bit of your personal life focusing on this, at times it can become a bit overwhelming,” she says.

But, unlike early career researchers, Professor Hughes has been doing this for a long time, which gives her a different perspective, she says.

“I’ve seen so much change,” she says. “I know what change looks like. I think we’re still failing, clearly; I mean, emissions keep going up. But the difference now is we know what to do. We have the tools to do it. And we have an abundant rationale. So, it’s not like there’s no action.”

LIFE GOES ON

Professor Hughes says she’s experienced moments where she just feels like it’s all too much.

“I cope with that by trying to be a normal person as well,” she says. “I have family. I like to do lots of things other than sit and think about climate change.’’

Professor Danielle Celermajer, a sociologist and environmentalist at The University of Sydney, says there’s an enormous amount of frustration, grief and exhaustion among people working in climate change research.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m going to completely nuts because it looks to me like we’re entering a level of devastation which is absolutely beyond anything that we can imagine and you talk to people about it and they just walk away from you because they don’t want to know,” she says.

Professor Celermajer appreciates the need for self-care but she’s personally a “terrible example”, she says.

Recently, a colleague sent her some meditations on radical self-compassion “and, you know, I opened it and I was like, ‘That’s really great’. And then I closed it and went back to work,” she says.

She’s got her own ways of relieving feelings of hopelessness, she says. “I’m kind of an outlier example. I live in Kangaroo Valley and I have a lot of rescue animals – horses and donkeys and sheep and goats and pigs.

“My direct relationship with them is probably the best thing that I have because it’s very immediate, like I can make a difference to their lives.”

DISMANTLING WORRY STORIES

“What are your choices when someone puts a gun to your head?”

“What are you talking about? You do what they say, or they shoot you.”

“Wrong. You take the gun, or you pull out a bigger one. Or, you call their bluff. Or, you do any one of 146 other things.”

– Suits, TV show

When people are faced with an existential threat and time appears to be running out, it triggers a fight or flight response, which can be paralysing, says Dr Jodie Lowinger, a clinical psychologist at the Sydney Anxiety Clinic.

Some people who are already predisposed to anxiety can get trapped in a cycle of catastrophic thinking about climate change, she says.

They will often repeat “worry stories” about the end of the world and about their inability to make a difference over and over in their mind until they start to seem true, she says.

Fortunately, we have evidence-based strategies, such as CBT, that can get people to challenge those worry stories and move them into a more helpful problem-solving headspace, says Dr Jodie Lowinger.

Once people break free from their physiological fear response, they can start to see what is actually within their control and how much they can personally do to make a difference.

Instead of conceptualising ecoanxiety as a disorder, we should encourage young people to feel proud that they are such deep thinkers and give them mental strategies to become eco-empowered, she says.

“People don’t need to suffer in silence with anxiety,” says Dr Lowinger. “Whether it’s in the clinical context or outside the clinical context, the right evidence-based strategies can be very helpful to make a difference in a matter of weeks or in just a couple of months.”

PROTECTIVE EFFECTS OF COMUNITY

“How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.”

– Anne Frank

Lucy Murdoch, a 16-year old from Geraldton (a regional town five hours drive north of Perth), says getting involved in the School Strike for Climate helps when she is feeling “terrified, overwhelmed, hopeless, small and insignificant”.

“I knew that for the sake of my own mindfulness I needed to be a part of something powerful and revolutionary,” she says.

“Joining School Strike for Climate made me feel included and capable, being surrounded by like-minded, driven youth was incredibly empowering.”

There’s a lot of wisdom in how many young people are dealing with climate change, says Dr Reem Ramadan, a clinical psychologist at youth mental health organisation Orygen.

“I’ve been so moved by seeing what young people are doing across the world,” she says.

“They are being really open and frank about how they’re feeling about this issue and joining together and forming communities and taking care of one another. And they are facing up to it, not pretending that it’s not happening. I think actually, a lot of us adults could learn a lot from them.”

While there’s little research into what helps alleviate ecoanxiety specifically, there has been research into what makes communities psychologically resilient following disasters.

After the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires, which killed 173 people and damaged more than 2000 properties, a five-year study was initiated by the University of Melbourne to track the health effects on communities.

The “Beyond Bushfires” study found that people living in rural areas were less likely to experience mental health issues after the bushfires if they were a member of a local community group, such as a football club, a sewing club or a church group.

“There’s something about just the opportunity to share information, resources, look out for each other that community groups provide,” says Professor Lisa Gibbs, an expert in community wellbeing and resilience at The University of Melbourne who led the project.

FINDING THE WORDS

People often struggle to describe how they are feeling about climate change because the words for our emotional connection to the Earth are not commonly used in Western culture.

The Inuit of the Artic have repurposed the word for “friend acting strangely”, ‘uggianaqtuq’ (pronounced OOG-gi-a-nak-took), to describe how climate change has impacted their culture.

The word ecoanxiety was first used in the literature in 1990, and terms such as “ecophobia”, “ecoparalysis”, “environmental generational amnesia” and “global dread” have been around since the 2000s.

But the word that has really clicked with people is “solastalgia”, which was coined by now-retired Australian philosopher and health ethicist Professor Glenn Albrecht.

Solastalgia derives from the word nostalgia and means “the feeling of homesickness that you have at home”.

This word was first used in 2003 to capture the feelings of the NSW Upper Hunter Valley community who had lost part of their environment to open cut coal mining.

Since then, it has taken on a life of its own, being used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, The Lancet, and academics all around the world in the context of climate change.

When the air becomes toxic, the sun changes colour, millions of animals are killed, bushland goes up in smoke or homes are reduced to smouldering ruins, that feeling of loss and longing for everything to go back to normal is something akin to solastalgia.

“People have found it incredibly distressing to see what’s happened to the forests of eastern Australia,” says Professor Albrecht. “The loss of human life and the loss of vertebrate and invertebrate life is almost incalculable.

“Now, if you didn’t have an emotional response to that, I think you would be clinically emotionally dead. And so, I take it as a good sign that Australians still have within them a hugely emotional response to this loss.

“Language is quite possibly the only public way that we can share the fact that we have common experience of these new stresses.”