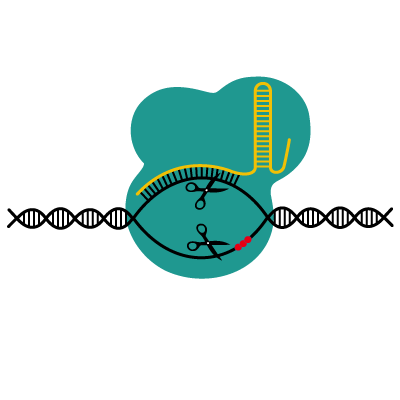

The striking news of the world's first gene-edited babies marks a sharp increase in the controversy surrounding human genome editing

The striking news marks a sharp increase in the controversy surrounding human genome editing. But this isn’t the first time a Chinese team has used the CRISPR technique on human embryos in a way that few researchers from other countries have attempted, and the country has claimed several firsts in the field.

The debate about China’s advances in this area broke out of laboratories and scientific circles a few years ago. In a 2015 New York Times article, “A scientific ethical divide between China and West”, Yi Huso, director of research at the Chinese University of Hong Kong Centre for Bioethics, stated: “I don’t think China wants to take a moratorium […] People are saying they can’t stop the train of mainland Chinese genetics because it’s going too fast.”

However, there are some important things to understand about the state of human genome editing in China today. First, access to surplus embryos in China isn’t much easier than anywhere else. On average, 83% of Chinese couples going through IVF procedures decide to keep their embryos up to three years after giving birth to a child. In the United States, approximately 62% of American couples keep their embryos up to five years after a birth. In France, of 220,000 frozen surplus embryos, just 20,000 can be made available for research, and less than 10% of those have been effectively used.

The new technological race

But China has entered a “genome editing” race among great scientific nations and its progress didn’t come out of nowhere. China has invested heavily in the natural-sciences sector over the past 20 years. The Ninth Five-Year Plan (1996-2001) mentioned the crucial importance of biotechnologies. The current Thirteenth Five-Year Plan is even more explicit. It contains a section dedicated to “developing efficient and advanced biotechnologies” and lists key sectors such as “genome-editing technologies” intended to “put China at the bleeding edge of biotechnology innovation and become the leader in the international competition in this sector”.

Chinese embryo research is regulated by a legal framework, the “technical norms on human-assisted reproductive technologies”, published by the Science and Health Ministries. The guidelines theoretically forbid using sperm or eggs whose genome have been manipulated for procreative purposes. However, it’s hard to know how much value is actually placed on this rule in practice, especially in China’s intricate institutional and political context.

In theory, three major actors have authority on biomedical research in China: the Science and Technology Ministry, the Health Ministry, and the Chinese Food and Drug Administration. In reality, other agents also play a significant role. Local governments interpret and enforce the ministries’ “recommendations”, and their own interpretations can lead to significant variations in what researchers can and cannot do on the ground. The Chinese National Academy of Medicine is also a powerful institution that has its own network of hospitals, universities and laboratories.

Another prime actor is involved: the health section of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which has its own biomedical faculties, hospitals and research labs. The PLA makes its own interpretations of the recommendations and has proven its ability to work with the private sector on gene editing projects. In January 2018, the Wall Street Journal reported that 86 patients had been enlisted into a clinical trial in an attempt to cure cancer. A Chinese start-up, Anhui Kedgene Biotechnology, was involved in this partnership with the PLA hospital 105, in Hefei province.

It is still to early to tell what is really at stake here. The Ng-Ago precedent should make everyone cautious of such major announcements: even published articles can be retracted, and peer-reviewed research amended. This announcement is not even at that stage.

This is clearly not the end of the story, just another dramatic step into the new age of gene editing.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.