The same may not be true of socialising or going to the flicks.

More evidence has just lobbed for the “use it or lose it” approach to cognitive function – and that means putting your thinking bits through a proper workout, not just taking them to the movies.

A team from Monash University, using 10 years of data from a 10,000-strong sample of the longitudinal prospective cohort study on older people known as ALSOP, set out to investigate “whether lifestyle enrichment in older relatively healthy individuals is associated with dementia risk, independent of education and health status”. The sample was overwhelmingly white and evenly split by sex, with an average age of 73.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open, includes data on social networks, frequency of leisure activities (“participating in club and group activities; taking education classes; using a computer; writing letters or journals; craftwork, woodwork, or metalwork; painting or drawing; playing games, cards, or chess; doing crosswords or puzzles; watching television; listening to music or the radio; and reading books, newspapers, and magazines”) and frequency of social outings (“attending libraries; restaurants or cafés; museums, galleries, or exhibitions; and cinemas or theaters”).

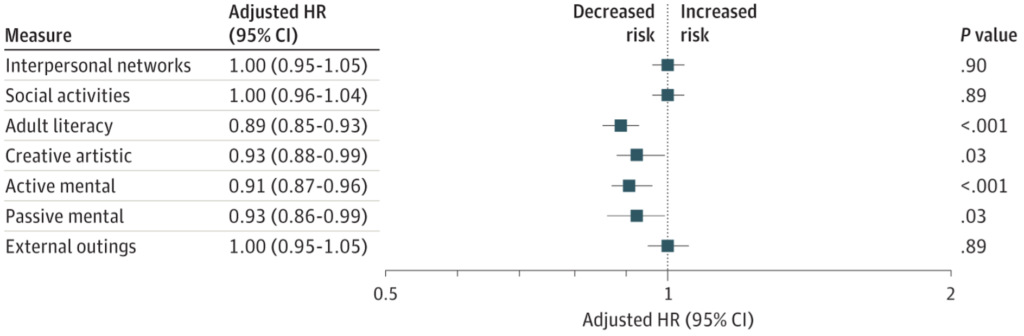

After adjusting for age, sex, race and ethnicity, education, area-level socioeconomic status, living situation, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activities, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, depression, and frailty, they found some very clear signals in the data:

Increasing adult literacy (education classes, using a computer, writing letters or journals) by one point on a five-point frequency scale, e.g. from “sometimes” to “often”, corresponded with an 11% reduction in dementia incidence over follow-up. Increasing active mental activities (playing games, cards, or chess or doing puzzles and crosswords) was associated with a 9% reduction.

These associations held when men and women were analysed separately; however, a reduction in risk associated with creative artistic pursuits held only for men. The weaker signal for passive mental activities went away.

Size of social networks and frequency of social outings had no relationship with dementia onset risk. This result surprised the authors, but they reason that the sample mostly comprised people with moderate or large networks, so the effects might be somewhat masked by a lack of real comparison.

The activities associated with the largest effects were the most cognitively stimulating, involving “proactive engagement, critical thinking, logical reasoning, and social interaction”. This work can increase resilience against brain pathologies, the authors write, “by increasing the number of neurons, enhancing synaptic activity, and permitting higher efficiency in using brain networks”.

Activities such as crosswords and puzzles and playing games, cards, or chess, are competitive and involve complex strategies and problem-solving. They use “a variety of cognitive domains, including episodic memory, visuospatial skills, calculation, executive function, attention, and concentration” as well as calling on language skills and pre-existing knowledge in the case of crosswords.

As for writing, that apparently is “a complex process of information output transferring thoughts into texts and using most cognitive abilities”.

The authors caution that their sample was likely to be healthier and more literate than average, and lacked racial and ethnic diversity, and say they cannot rule out reverse causality altogether.

Your Back Page correspondent draws two lessons. 1) We should keep up our pathetically slow efforts to improve at chess, no matter how often we have our dignity handed to us by a cheerful bot called Sven (1100, defensive) or Maria (1200, loves to sacrifice). 2) We should keep “using most cognitive abilities” in the form of writing this column, for our own sake if not the readers’.

Sending story tips to penny@medicalrepublic.com.au wards off brain pathologies through enhanced synaptic activity.