As our population ages, adverse drug interactions in geriatric patients are becoming an increasing problem

New symptoms in your geriatric patient? Before reaching for the path order form or the radiology request, check their drug cupboard, geriatricians suggest.

Drug-drug interactions are very common and often go unrecognised among elderly patients, with side-effect symptoms mistakenly prompting disease investigations, the authors of a recently published paper in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society say.

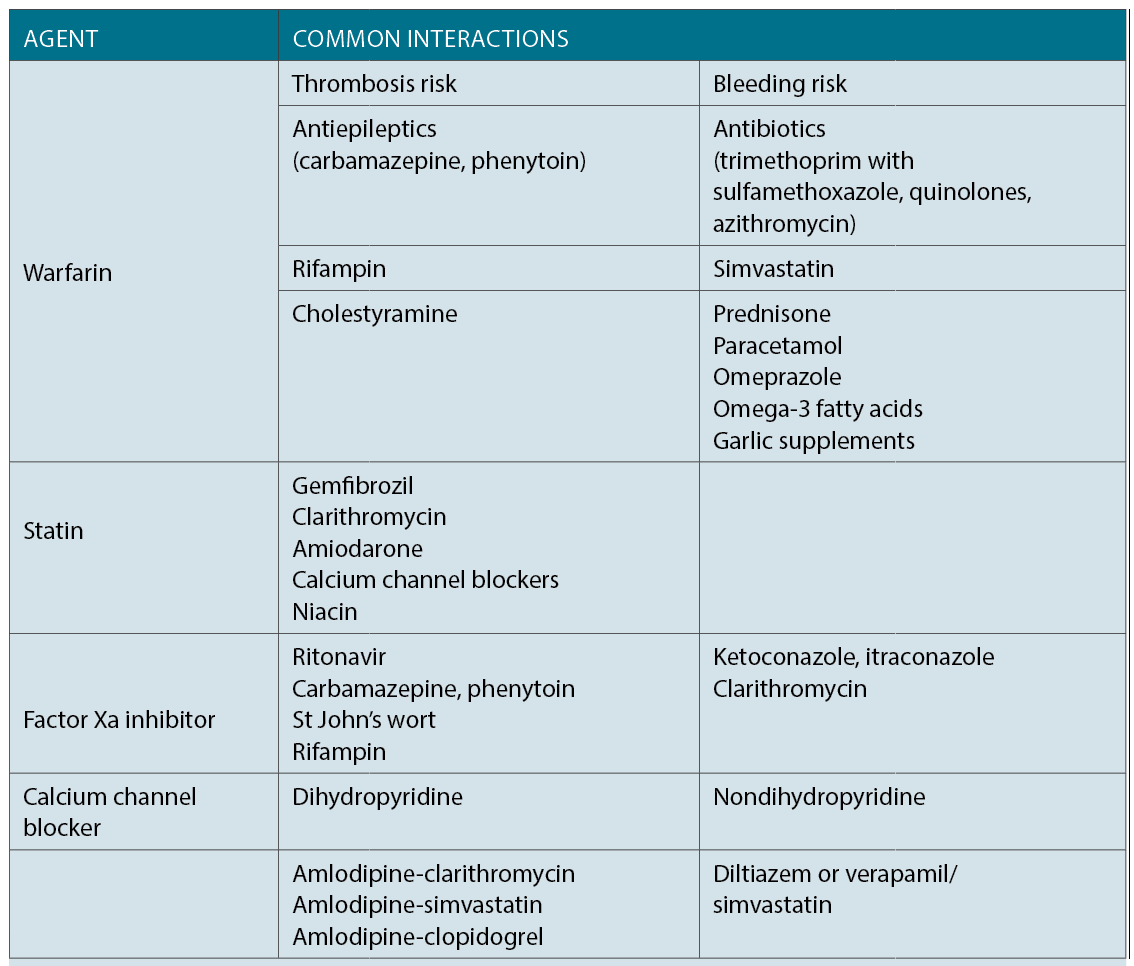

According to the US authors, four common agents or classes of drugs with particular risks for drug-drug interactions among the elderly were statins, warfarin, factor Xa inhibitors and calcium channel blockers.

The antibiotic, clarithromycin when taken with a factor Xa inhibitor, such as rivaroxaban, dabigatran or apixaban, increased the bleeding risk, they wrote.

Conversely, patients on a factor Xa inhibitor who also took St John’s wort, carbamazepine or rifampin were subject to decreased efficacy of the anticoagulant and had an increased risk of thrombosis.

Professor Sarah Hilmer, head of the department of clinical pharmacology at Royal North Shore Hospital, said an ageing population with multimorbidity and polypharmacy meant drug interactions were only going to be an increasing problem.

One in three older patients were on 10 or more drugs, and research shows that being on 10 or more drugs comes with a 50% chance of having a clinically relevant drug-drug interaction, and around a 12% chance of having a very serious drug-drug interaction, she said.

Professor Hilmer said it was really common for clinicians to mistakenly investigate for disease in patients presenting with drug side-effects.

“The most reversible cause of a geriatric syndrome is an adverse drug reaction,” the geriatric pharmacologist said. “And a lot of the time in older people, adverse drug reactions present non-specifically as the geriatric giants of falls, confusion, a sudden sort of failure to function or failure to cope.”

Much of the time the drug was not the only cause of the presentation, but rather the “straw that broke the camel’s back” and the one that could be fixed.

The complexity of managing drug interactions in the elderly is compounded by the fact that medical research tends to be done on younger, healthier patients.

As a result, “it [is] more difficult to make informed decisions about how much a particular medication is likely to benefit an older adult,” the authors wrote.

Improving management was going to rely on constant vigilance and keeping adverse drug reactions in mind when somebody presented with any symptoms, Professor Hilmer said.

Other lesser known side-effects included hyponatremia with SSRIs, which was particularly a risk for women, the authors said. And trimethoprim with sulfamethoxazole was linked to hyperkalaemia, particularly in patients with poor renal function.

PPI side-effects included an increased risk of Clostridium difficile infection in patients on an antibiotic, and fractures.

Older patients were more susceptible to Achilles-tendon rupture when taking fluoroquinolones, and this was made worse by concurrent corticosteroid use, the authors said.

In addition to the four classes and agents outlined in the paper, Professor Hilmer highlighted SSRIs as another class with serious pharmacodynamic interactions.

Antidepressants, analgesics such as tramadol and tapentadol, and St John’s wort all increased the risk of serotonin syndrome, she said.

In elderly patients, medication side-effect symptoms such confusion, agitation or dysregulation of temperature might be missed.

One of the commonest prescribing cascades Professor Hilmer said she saw was when patients who were put on cholinesterase inhibitors to improve cognition for Alzheimer’s disease, wound up with side-effects from the increased cholinergic transmission and were then put on anticholinergic drugs. e interactions in people who took multiple medicines for mulitmorbidity were also very common, she said.

J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; online 21 March