Deleting data about the spread of bird flu to felines is a step too far, Elon.

On 5 February the US Center for Disease Control briefly posted, and then deleted, a table about bird flu transmission that involved cats.

It did not go unnoticed, and has become symbolic of the suppression of health information since Donald Trump returned to the White House.

The table referred to two cases of cats who died from bird flu after possibly being infected by their owners, who worked in the cattle industry.

“In one household, an infected cat might have spread the virus to another cat and to a human adolescent,” The New York Times reported after obtaining a copy of the data table.

“The cat died four days after symptoms began. In a second household, an infected dairy farmworker appears to have been the first to show symptoms, and a cat then became ill two days later and died on the third day.”

(Fires are important to learn about too but timely biosecurity is a very odd choice to skip.)

Also, they accidentally included a chart about cats and bird flu in the fire article.

What’s going on? Who knows, but it’s not pretty.

[image or embed]— Katelyn Jetelina (@kkjetelina.bsky.social) February 7, 2025 at 12:32 PM

H5N1 is a live issue in the Big Apple. Live poultry markets have been temporarily shut down in NYC and three neighbouring counties following the detection of seven cases of bird flu in poultry.

We know that cats get infected. In 2023, an outbreak in Poland killed more than 30 pet cats, many indoor-only, who contracted the virus possibly by eating raw pet food from infected mink farms. A Texas dairy farm outbreak in February last year involved dead cats on several farms.

“Spillover from cattle to domestic barn cats probably occurs through ingestion of contaminated, unpasteurized milk. Scavenging dead birds is also a way for cats to become infected,” according to a round-up of the global H5N1 influenza panzootic in mammals published in Nature last September.

There are different versions of the virus circulating. The Polish cats, for example, had an adaptation that was different to the contemporaneous virus in birds. As time goes on, H5N1 continues to mutate, and the concern is that it will do so in a way that better infects people. Where it has infected people, figures collected by the WHO from January 2003 to September 2004 show a 54% fatality rate.

Back to cats. The data in question was initially in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), but the report now online only addresses the Los Angeles County fires. No mention of H5N1, with or without cats.

Epidemiologist Dr Jennifer Nuzzo, from Brown University’s School of Public Health, said the “slowdown” in communication with their new government meant there was a corresponding slowdown in dealing with the H5N1 threat.

“This virus is not slowing down. It is really spreading,” Dr Nuzzo said in an interview with Boston public radio station WBUR-FM.

“Information and communication is possibly the most important public health intervention we have. When you’re dealing with a new virus, we need to collect data and relay that to everyone who needs to know.

“We know there’s been a categorical pull-back on information coming out of our federal health agencies on multiple fronts, in abilities to talk to CDC, to talk to local health departments, pull-back on websites, a pull-back on the CDC’s scientific journal, MMWR.

“This is really not the time. Right now we need more information, not less.”

Anyhow, back to cats. The CDC weekly report, which was paused for two weeks in compliance with federal orders, was supposed to contain scientific reports about H5N1: one on infections among livestock veterinarians from cattle, another on people working in the cattle industry infecting their pet cats.

They were supposed to be published in the report interrupted by the “pause” order, according to a CNN Health article published on 30 January.

“A person close to the CDC, speaking on the condition of anonymity because of concerns about reprisal, expected the MMWR to be on hold at least until Feb. 6. The journal typically posts on Thursdays, and the HHS memo says the pause will last through Feb. 1.

“It’s startling,” Tom Frieden, a former CDC director, told CNN.

The article goes on: “He added that it would become dangerous if the reports aren’t restored. ‘It would be the equivalent of finding out that your local fire department has been told not to sound any fire alarms,’ he said.”

Although I’m encouraged that the MMWR is being published again, I’m surprised and concerned that it doesn’t contain any reports on bird flu spreading in animals and people, the new strain of mpox spreading or other emerging health threats.

— Dr Tom Frieden (@drtomfrieden.bsky.social) February 7, 2025 at 9:10 AM

[image or embed]

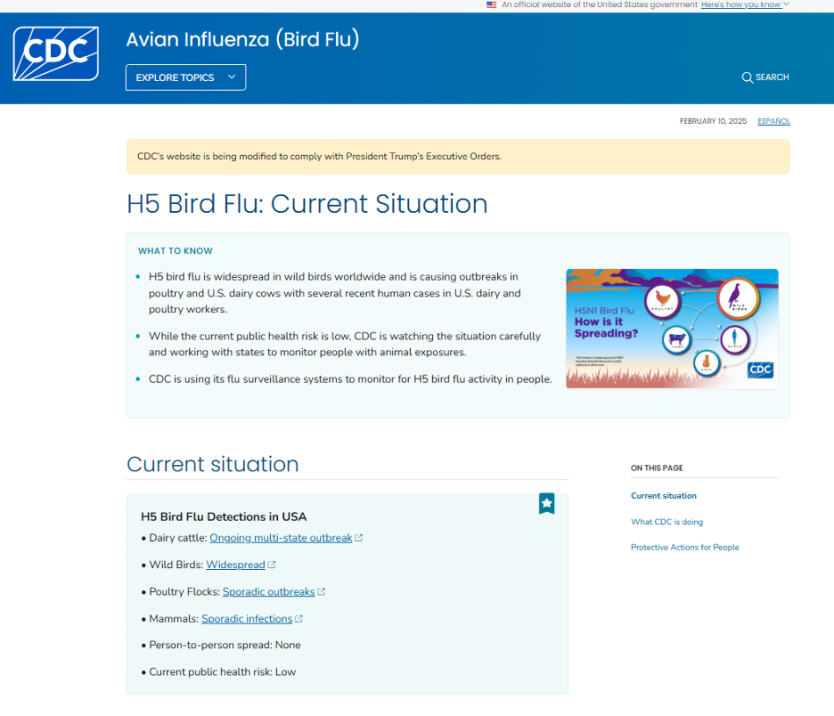

Here’s what the CDC website says looks like at the time of writing.

Why don’t they want us to know about the cats?

Dr Bruce Y Lee, Professor of Health Policy and Management at the City University of New York, frames it rather well, though he’s not talking only about cats:

“Anytime scientific communication is hampered, you’ve got to worry about the ‘c’ word: censorship. You’ve got to ask who is controlling the flow of scientific information and for what reason,” he writes.

The Back Page is no political pundit, but let’s go out on a limb – a crowded one, which might actually make it more dangerous.

Sure, pandemics are awful for the people who get sick and die and their families and friends and all that.

But have you stopped to think for a minute what a pain they are for governments, especially those whose voter base don’t believe in pandemics, and don’t want mitigation measures, especially if they might interfere with industries that involve animals somewhere along the chain?

Fellow cat ladies and cat chaps, we have a right to know.

Send your cat snaps and story tips to penny@medicalrepublic.com.au.