Five patients with severe illness are in remission after a treatment normally used to treat B-cell lymphomas.

Speaking at the recent Australian Rheumatology Association ASM, Professor Georg Schett, vice-president of research at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Germany, said that since lupus was a B cell-driven disease, there had long been efforts to block B cells in some way.

Some studies have explored rituximab for B cell depletion in lupus, which Professor Schett said had had mixed results because the treatment was effective at depleting circulating B cells but not those in tissue.

Newer monoclonal antibody therapies such as obinutuzumab were also effective at targeting B cells via the CD20 antigen, which was able to reach B cells in the bone marrow, but this antigen was less present on plasmablasts and plasma cells.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy involves harvesting a patient’s T cells, engineering them to carry a receptor for CD19-positive B cells, then infusing them back into the patient. The T cells then target B cells carrying this antigen – which includes plasma cells – and kill them.

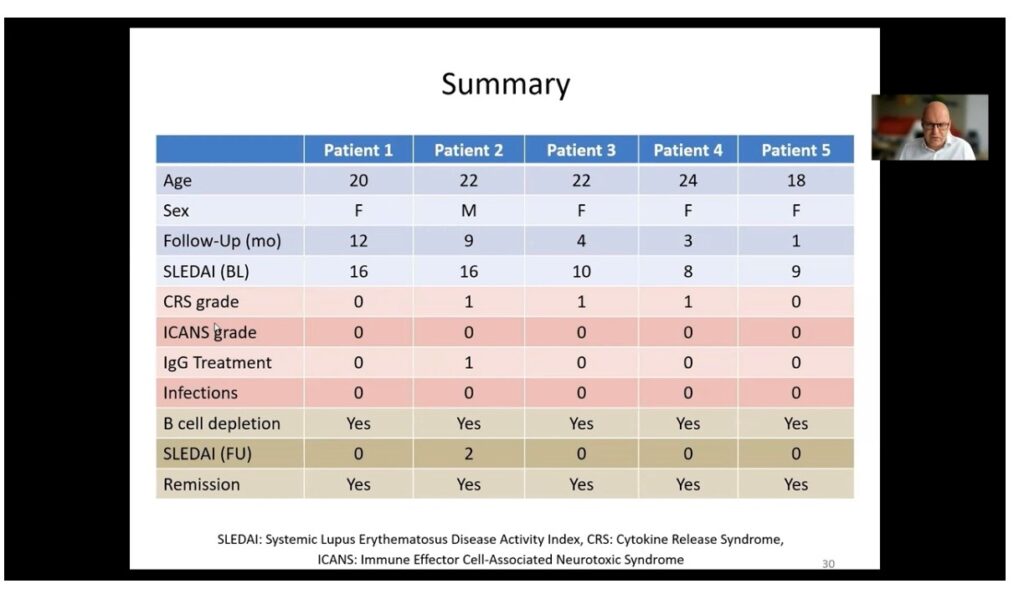

Professor Schett and colleagues used CAR T-cell therapy in five patients with severe lupus and high disease activity scores, including one 20-year-old woman with severe, treatment-refractory lupus featuring nephritis, pleurisy, endocarditis, arthritis, fatigue, rash and very high levels of autoantibodies.

After harvesting, transducing and expanding the T cells, they were infused back into the patients.

Researchers saw a rapid expansion of the CAR T-cells in the nine days after infusion, during which time B cell populations were reduced to undetectable levels. Anti-dsDNA antibodies also declined rapidly and disappeared entirely after 21 days, C3 and C4 complement factor levels normalised, and proteinuria completed resolved within 30 days of treatment.

The SLEDAI scores in all five patients dropped well below the margin for remission, and all five remained in remission over the 300 days of follow-up, despite a recovery of B cell populations in at least two patients.

“We think that this is based on the fact that there is a deep reboot of the immune system,” Professor Schett told the conference. “It is like a baby immune system which comes back, and there is potentially no autoimmunity.”

The CAR T-cell levels peak at around day nine after infusion, then steadily decrease to very low or undetectable levels after one month. Professor Schett said the safety profile of the treatment was very good, with only one patient experiencing grade one cytokine release syndrome in the form of mild fever for two days. The adverse event profile was surprisingly better than that seen in lymphoma patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy.

An audience member raised the question of the duration of B cell depletion, and how it compared to that achieved with rituximab. Professor Schett said the duration of effect was probably similar, but the difference was that CAR T-cell therapy achieved a much deeper depletion of B cells.

“I think it’s a remarkable development and a huge chance for very severe patients with autoimmune disease, particularly given that all these patients completely stopped their treatment and had no treatment anymore after a single infusion of CAR T-cells,” he said.

CAR T-cell therapy for autoimmunity – is it feasible and what can we expect?