The demand for treatment of cannabis use is increasing. So what is the evidence for cannabis-related harms?

Cannabis is the most common illicit drug of dependence in the Western world. The 2013 National Drug Strategy Household Survey reported that around one in 10 Australians (10%) aged over 13 years had used cannabis in the previous year, and more than a third (35%) had used it at least once.1 Among recent cannabis users, 13% said they were daily users.

The age group with the highest prevalence of recent cannabis use are 20 to 29-year-olds, with 25% of males reporting recent use.

The rapidly evolving changes in medicinal cannabis policy nationally, with various accompanying state regulations, have placed GPs at the centre of cannabis policy and practice. As the smoke clears on the many related issues over the years to come, there’s an increasing need for screening, assessment and intervention options for cannabis use disorder and related problems.

While most cannabis use is experimental and occasional, approximately 6% of the total Australian population will meet criteria for cannabis dependence in their lifetime, and 1% for the past 12-months. Of those who used at least five times in the previous year, 14% met the criteria for cannabis dependence.

In light of the soon-to-be-introduced medicinal cannabis use in Australia, it is concerning to note that since medicinal cannabis became available in the US, typically with more liberal regulation than proposed here, one in three cannabis users are now daily users. And the concentration of use among poorer households means that many users are spending a high proportion of their income on their cannabis habit.2

These findings support the argument for policy changes affecting cannabis availability to be accompanied by public health protections, and the increased need for GPs to be across the evidence for cannabis-related harms and detection and management of related problems.

The US Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM V) has amended the nomenclature from “abuse and dependence” to a “cannabis use disorder severity” continuum. Current cannabis use disorders are more common among males and younger users. Those using cannabis before the age of 17 years were 18 times more likely to develop cannabis use disorder by age 30 years than those not using cannabis during that period.3

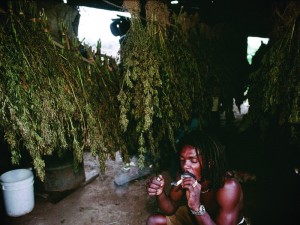

HARMS

While cannabis has a very low acute toxicity, cannabis-related morbidity presents a major public health burden. A recent study of cannabis-attributable mortality and morbidity reported a relative risk greater than two, based on at least 50 cannabis use occasions.4 Cannabis use disorder is the most common harm. Those with the condition are at a higher risk of suffering from the negative consequences of using the drug, such as short-term memory impairment, mental health problems and respiratory diseases if cannabis is smoked. Regular use and cannabis use disorder can also lead to problems with finances, conflict in relationships with family and friends, and problems with employment.

As cannabis is almost always smoked, and most often mixed with tobacco in blunts or smoking mixtures, there is also the risk of adverse respiratory effects. These include respiratory problems of chronic cough, sputum production, wheezing and bronchitis, even after controlling for tobacco use.

Cardiovascular events, such as stroke and heart attack, are also potential health risks.

Certain groups of people may be at a higher risk of developing the adverse acute and chronic effects of cannabis. These groups include adolescents, pregnant women, those with respiratory or cardiovascular disease or vulnerability, and those with comorbid disorders. The onset of cannabis use in early adolescence poses particularly high risks of serious adverse physical and mental health and social / academic consequences, including increased risk of depression and anxiety, and lower academic achievement – again potentially persisting into adulthood.

There is also evidence to suggest that cannabis use increases the risk of suicide attempts, particularly among the young.3

The issue of the comorbidity with other substance use disorders (such as cannabis and alcohol use disorders) and with other mental health disorders (anxiety, depression or schizophrenia) is a clinical concern, and occurs relatively frequently. Cannabis use in those vulnerable to psychotic disorders precipitates the manifestations of the disorder on average three years earlier, increases rates of non-compliance with medication, and increases hospitalisations. In addition to the direct effects of the drug on the psychological and physical health of the user, cannabis use increases the risk of injury or death while driving, or operating equipment at work.

PRESENTATIONS AND SCREENING

Despite the availability of effective treatments for cannabis use disorders, only a minority of patients will identify their cannabis use as problematic. Various barriers can inhibit treatment seeking, such as being unaware of treatment options, thinking treatment is unnecessary, wanting to avoid the stigma associated with accessing treatment, concerns about confidentiality, lack of accessibility, and costs of treatment. When adults do present for treatment of cannabis use disorder, they typically have used cannabis for ten or more years, and had multiple failed attempts to quit. Adolescent cannabis users are usually coerced by families, schools or the legal system to present for treatment.

Cannabis users may seek assistance for problems such as poor sleep, anger, depression, anxiety, psychosis, relationship issues, or respiratory problems, but not disclose their cannabis use to their GP.

ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

The flow chart on page 38 sets out the steps in the assessment and brief management of cannabis users and cannabis-related problems.

The Severity of Dependence Scale is a quick five-item measure of the degree of dependence to cannabis, which is ideal for a GP practice as a brief screener.

The importance of simple screening and brief advice, with provision of psychoeducational materials, cannot be overemphasised. Even very brief interventions of around 20 minutes have been shown to positively influence levels of cannabis use among non-treatment-seeking cannabis users.

The demand for treatment of cannabis use is increasing. Almost one in 24% clients attending specialist alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia are presenting for a problem related to cannabis use. Adult cannabis users who seek professional help typically report numerous problems related to their cannabis use, some clearly related to core dependence criteria, such as an inability to stop or cut down, and withdrawal symptoms.5 Other issues prompting treatment include relationship, family and financial difficulties, health concerns and poor life satisfaction.

MANAGEMENT

Where the patient is interested in further discussion of their cannabis use, psychoeducation about cannabis (examples provided in resource list) and one to six sessions of cognitive behavioural therapy within a motivational interviewing framework has the strongest evidence-base.

WITHDRAWAL

One of the main barriers to abstinence is cannabis withdrawal symptoms. The most troubling withdrawal symptoms include irritability/ restlessness, low mood, sleep disturbance and gastrointestinal discomfort. Cannabis withdrawal symptoms can have a significant impact on attempts to quit, and are associated with functional impairment to daily activities, substance use to alleviate cannabis withdrawal symptoms and increased frequency of cannabis use. The duration is typically five to seven days, with symptoms peaking on days one and two.

The withdrawal effects on sleep may last weeks or even months. Cannabis withdrawal symptoms among those dependent on cannabis are also strongly associated with relapse, highlighting the importance of ongoing assessment and monitoring of withdrawal symptoms as part of treatment.

PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTIONS

The majority of those with cannabis use disorders go on to manage their disorder and / or abstain from use without formal treatment. The strongest evidence base is for individualised psychosocial interventions.

The primary approaches to the planning, cessation and maintenance, or reduction of, cannabis use have included motivational enhancement therapy (MET), cognitive behaviour therapy and contingency management. Supportive psychotherapy and family systems approaches also have some potential.5 Support groups, such as a 12-step program and SMART Recovery (self-management and recovery training), can also be of assistance for some patients and families. A core skill is motivational enhancement therapy. This therapy aims to resolve ambivalence around changing cannabis use behaviours, thereby increasing motivation to change. The tenets of the therapy rest on empathy and non-judgemental interactions, using open-ended questions and validation, increasing cognitive discrepancy between actual and desired behavioural states, avoiding confrontation and supporting clients’ own self-efficacy. Studies on brief two-session motivational interventions with adolescent cannabis users have shown promising results in boosting motivation for change and reducing cannabis use.

COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY

CBT focuses on altering the learned behaviour of cannabis users so as to increase the opportunity to use adaptive behaviours instead. The therapy focuses on recognising and limiting the “cues and use” circumstances, and moderating the precipitators of drug use. CBT has proven to be beneficial in the treatment of cannabis dependence, and can be combined with pharmacotherapy.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

There are currently no evidence-based pharmacotherapies for the management of cannabis withdrawal or craving. The early-stage studies of pharmacotherapies have largely focused on cannabis withdrawal. The agonist therapies have shown the most promise. The most innovative and promising is nabiximols (Sativex).

This drug has demonstrated efficacy for the reduction in the severity and time course of cannabis withdrawal. It also appeared to increase retention of participants in withdrawal treatment. A community-based trial of nabiximols for cannabis withdrawal is currently underway in NSW and a study of cannabidiol for cannabis craving among young men with mood and cannabis use disorders is due to commence in Sydney soon.

Cannabis use and cannabis use disorders are common. They frequently co-occur with other substance use disorders and mental health conditions, and should be assessed and treated concurrently.

There is no evidence-based pharmacotherapy for cannabis use disorder, but recent studies with agonist therapies have shown promising early results. The strongest evidence for treatment efficacy is for one to nine sessions of CBT, with predictors of successful treatment including active coping strategies and distress tolerance.

The evidence base for interventions via technological platforms such as computers, telephones and smart phone applications as prevention and intervention tools is also being established.

Professor Jan Copeland is the founding Director of the National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre at UNSW Medicine. The NH&MRC study she led into Sativex (nabiximols) was provided the drug by GW Pharmaceuticals at no cost and with no other consideration. She does not consult for, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

References:

1. AIHW. National Drug Strategy Household Survey Detailed Report 2013. Series 28. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2014.

2. Davenport SS, Caulkins JP. Evolution of the United States: Marijuana Market in the Decade of Liberalization Before Full Legalization. J Drug Issues [Internet]. 2016; Available from: http://jod.sagepub.com/lookup/doi/10.1177/0022042616659759

3. Silins E, Horwood LJ, Patton GC, Fergusson DM, Olsson CA, Hutchinson DM, et al. Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: An integrative analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. Elsevier Ltd; 2014;1(4):286–93.

4. Imtiaz S, Shield KD, Roerecke M, Cheng J, Popova S, Kurdyak P a, et al. The burden of disease attributable to cannabis use in Canada in 2012. Addiction. 2016;653–62.

5. Gates PJ, Sabioni P, Copeland J, Le Foll B, Gowing L. Psychosocial interventions for cannabis use disorder. Cochrane database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Jun 3];5:CD005336. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27149547

Resources:

https://ncpic.org.au/professionals/health-care/gp-toolkit

https://ncpic.org.au/professionals/publications/factsheets/cannabis-and-young-people https://ncpic.org.au/professionals/publications/factsheets/cannabis-and-dependence

https://ncpic.org.au/media/1552/do-it-yourself-guide-to-quitting.pdf

https://ncpic.org.au/professionals/publications/factsheets/cannabis-withdrawal

https://ncpic.org.au/media/1590/severity-of-dependence-scale-1.pdf

https://ncpic.org.au/cannabis-you/tools-for-quitting/quit-kit/

Copeland J, Rooke S, Matalon E. (2015). Quitting Cannabis. https://www.allenandunwin.com/browse/books/general-books/health-fitness/Quit-Cannabis-Jan-Copeland-with-Sally-Rooke-and-Etty-Matalon-9781743319925

https://ncpic.org.au/professionals/publications/bulletins/very-brief-interventions/

https://ncpic.org.au/shop/all-resources/