As long as the more harmful drug is easily available, the government has no leg to stand on in maintaining prohibition on recreational weed.

In Australia “medicinal” cannabis is legal while “recreational” cannabis is not, yet there is no clear line between the two, only a continuum.

Allow me to set the scene. In November the AMA released the following statement opposing the Legalising Cannabis Bill 2023:

“The AMA is concerned that if cannabis were legalised for recreational purposes, it may increase health and social-related harms. This in turn may increase demand on an already overstretched healthcare system. The AMA supports methods to reduce the disproportionate rates of incarceration for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, including decriminalising personal cannabis use, and raising the age of criminal responsibility to 14. The AMA is also concerned that people may use recreational cannabis products to self-medicate when Australia already has an existing, high-quality process for assessing the safety, quality, and efficacy of therapeutic products through the TGA.”

Doctors form a broad church, which is a good thing. The AMA represents less than 30 per cent of a total 130,000 doctors in Australia. I am a current member and sit on the Clinical Council of AMAQ. The following are my own views and do not represent the views of any organisation with which I am associated.

What cannabis can do

The wide range of cannabinoid products, mainly CBD/THC components, have proven medical utility in some conditions such as multiple sclerosis, chemotherapy-induced nausea, AIDS-related wasting syndrome (as an appetite stimulator), and in two specific forms of severe childhood epilepsy. Beyond these conditions the research waters are muddied by industry-subsidised research that sees a place for CBD/THC products in almost any condition bar dandruff. Perhaps over time the evidence will be independently verified.

Before the War on Drugs, cannabis was listed in the US Pharmacopoeia in 1851 and was used for a wide variety of maladies, such as tetanus, neuralgia, alcoholism, convulsions, dysmenorrhea, and rheumatism. Sir William Osler, considered by medical historians to be the father of modern medicine, claimed that “cannabis indica is probably the most satisfactory remedy for migraine”.

As I recall, the War on Drugs launched in the US by Harry Anslinger was to a large measure driven by racism, xenophobia, and a need to redeploy a massive workforce that had been created to support alcohol prohibition.

My instinct is that cannabis will become available for recreational use in Australia within the next five years. Money talks and in 2021 the combined market capitalisation in Australian the “medicinal” cannabis industry was more than $2 billion. I sense that medicinal cannabis is the Trojan Horse, strategically introduced to foster conversations about the ambiguity and duplicity in the present mainstream conservative narrative.

Business or pleasure?

For over 3000 years it seemed reasonable to manage stress by taking attractively packaged rotten fruit (alcohol), cannabis, or other similar psychoactive products. Seeing a market, the pharmaceutical industry developed various forms of minor and major tranquillisers, e.g., barbiturates, benzodiazepines etc. So now, if I want to assuage my stress I can have “recreational” alcohol, but I can’t take recreational TGA-approved products.

Yet there is strong evidence that alcohol is more harmful than cannabis, while at a population level, the criminalisation of cannabis has negative public health consequences on a significant portion of the community.

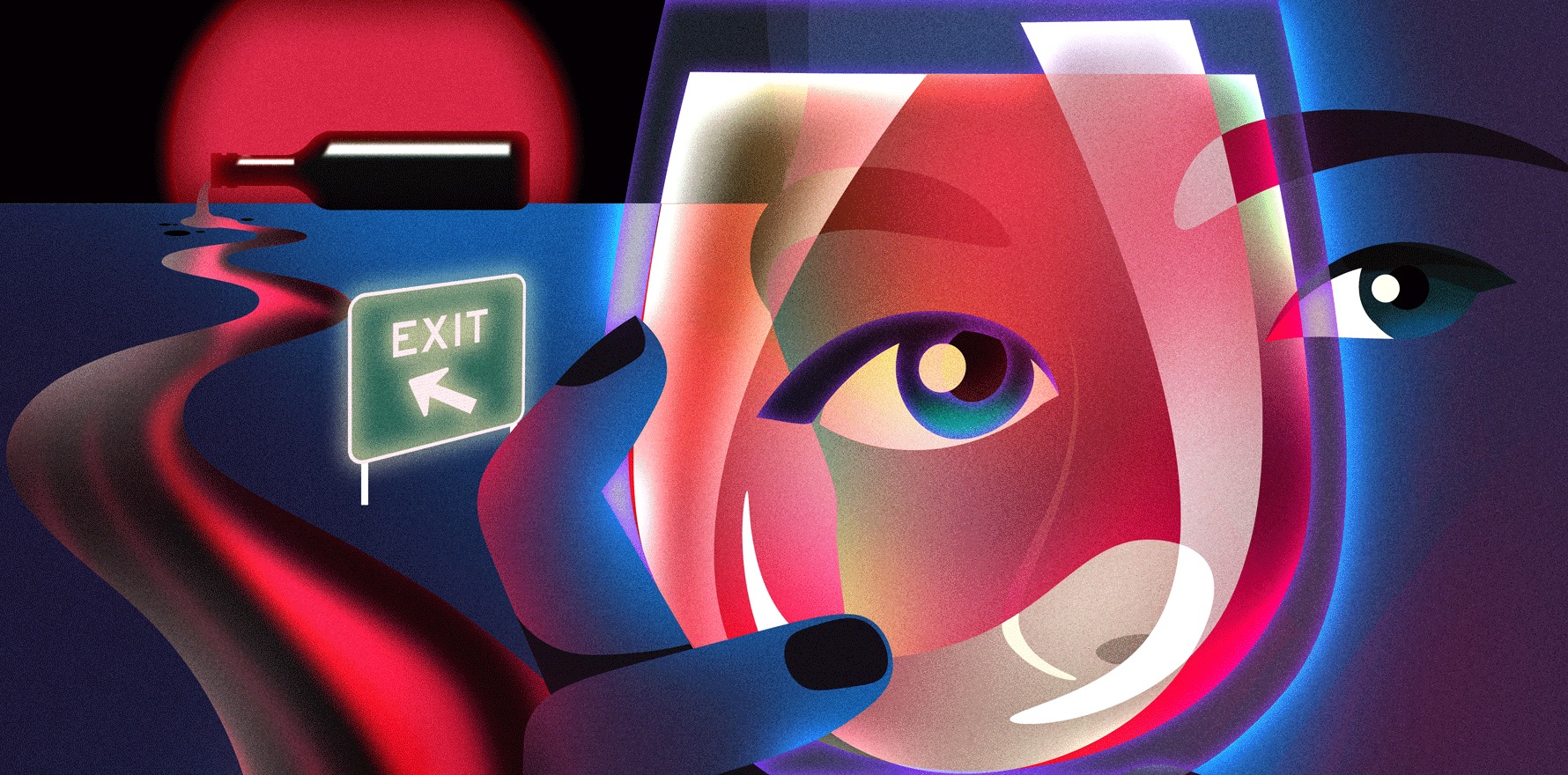

Cannabis might also work as an exit ramp as well as a “gateway drug”, especially an exit from the more harmful alcohol.

Alcohol increases the risk of many cancers, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic illnesses. WHO regards alcohol as a toxin, where there is no safe dose. Government safe-drinking guidelines have no evidence base, being instead determined by a social contract between the public and the government. So, with respect to pure evidence-based science, the ambiguity and duplicity of which I speak would be quashed if alcohol were subject to TGA scrutiny.

Related

I accept that cannabis has significant negative health effects. It is not generally recommended for children or adolescents. Sadly, half a century of criminalisation has not prevented 12-year-olds accessing weed in their school playgrounds. Under-15s are at the highest risk of negative neurological sequelae from cannabis use. This includes cannabis use disorder (CUD) at an estimated prevalence of 25 per cent in adolescence.

Here is where it gets interesting. It has been reported that around 22 per cent of people prescribed medicinal cannabis meet the criteria for CUD. In contrast, 9 per cent of adult recreational users will develop CUD, which is the same percentage of alcohol users with alcohol use disorder.

The dictionary defines recreational use of a drug as being for “enjoyment rather than to treat a medical condition”. A path from unhappiness to happiness, from stress to pleasure. But Big Pharma has successfully medicalised unhappiness and stress – so the medicinal/recreational distinction crumbles.

Unhappiness is also a predictor of pain, and a recent metanalysis demonstrated that alcohol delivers effective pain relief. Up to 28% of people with chronic pain turn to alcohol to alleviate their suffering. A larger percentage drink to allay anxiety. No medicinal/recreational distinction is demanded here.

The Pennington Institute’s report Cannabis in Australia 2023 found, using data from the Special Access Scheme B, that almost half of medicinal cannabis is prescribed for chronic pain and a third for anxiety, though neither is among the conditions indicated by nonpartisan science for therapeutic cannabis.

Time for policy

Five years after legalisation of cannabis, Canada’s sky had failed to fall in. What the data did show is that the medicinal cannabis market was decimated by decriminalisation. In Canada the major consumer group of recreational cannabis were the 50-to-60-year-olds. Legalisation did not create a new market, it was already there.

If we accept that sanctioned recreational use is simply a matter of time, the conversation should turn to policy settings.

The considerations are many and include: capping potency to a certain percentage of THC; restricting delivery methods such as smokables or vaping in favour of edibles; open-slather commercialisation versus restricting licensing to independent pharmacies or not-for-profit NGOs.

It is important that those selling the product are cannabis-literate, being not only shopkeepers but also gatekeepers. Medical practitioners will need to be better informed, as there will be emerging data about drug interactions and the identification of at-risk groups.

Prohibition is still with us

History tells us that humans will always use drugs and it is societies’ responsibility to support policies that minimise harm.

No one deliberately sets out to have an unhealthy relationship with a substance; drugs themselves do not create an addiction. Unhealthy relationships with substances are the tip of the iceberg and underneath the waterline there exists Adverse Childhood Events, social networks, and toxic environments.

Let’s stop pretending that medicalising a pleasurable psychoactive substance and creating a medical gatekeeper is not just another form of prohibition. The fact that cannabis works as a medication in some instances at a specific dose is a happy coincidence to be studied free of controversy and corporate interests.

The only other way to resolve the ambiguity and duplicity around psychoactive substances would be to have alcohol regulated by the TGA. I wager that will never happen. So why is an alcohol-equivalent substance like cannabis a Schedule 8 drug under the TGA?

Perhaps this is just a part of the journey towards reasoned legalisation.

Associate Professor Kees Nydam was at various times an emergency physician and ED director in Wollongong, Campbeltown and Bundaberg. He continues to work as a senior specialist in addiction medicine and to teach medical students attending the University of Queensland Rural Clinical School. He is also a poet and songwriter.