Around half of all cancer deaths in Australia may be preventable, we just need political will.

If you were around in the 1980s, you probably remember the anti-smoking campaign featuring black tar being squeezed from a sponge. The message was clear. If you smoked, that’s what your lungs looked like.

And the Artery campaign of the 2000s, starring beige goo squelching out of an aorta, remains vivid in the memories of a generation.

In Australia, hard-hitting messaging, coupled with policy measures that banned smoking in workplaces and public spaces, and put graphic images on tobacco products, led to a steep drop in smoking rates.

Over the past 20 years, the proportion of smokers in the population fell from 25% to around 11%.

Despite that, tobacco is still by far the biggest avoidable killer, both here and internationally, causing 34% of preventable cancer deaths around the world. That’s followed by alcohol use and high BMI.

Those are the findings of an analysis published in The Lancet, of the Global Burden of Disease project data, which recorded the toll of cancer worldwide from modifiable risk factors such as behaviour, environment, occupation and metabolic issues.

It’s a mammoth dataset that includes 204 countries, 34 risk factors and 23 types of cancer to uncover how many people died from cancers caused by avoidable risks in one year.

Those modifiable factors were responsible for around 45% of all cancer deaths, (50% in males and 36% in females). That’s equivalent to 4.45 million deaths and 105 million disability adjusted life-years (DALYs). In Australia, preventable deaths attributed to cancer accounted for around 40% of all cancer deaths and DALYs.

The lower proportion is partly due to a death rate of less than 1% for cervical cancer thanks to our vaccination and screening program, compared to the global average of 18%. But smoking, drinking and obesity are still heavy hitters here.

Tobacco was overwhelmingly the largest preventable risk factor, causing one in five cancers from modifiable risks, followed by alcohol at 7% and high BMI at around 6%.

The authors called for policies aimed at reducing the nation’s cancer risk factor burden. But Australian experts say this just isn’t happening here.

CALLS FOR SYSTEMIC CHANGE

The issue in Australia is the commercial determinants of health, says Associate Professor Brigid Lynch, deputy head of Cancer Epidemiology at Cancer Council Victoria.

“As we saw with tobacco control, these companies have vested interests in selling their products,” Professor Lynch says.

“Big businesses that sell unhealthy products. Whether it’s tobacco or alcohol, soft drink or unhealthy food, all use insidious marketing techniques. And from a very young age, people are bombarded with advertising on their social media.

“We saw with tobacco control that it was a multi-systems level approach that drove down smoking rates.”

Melanoma rates, for instance, have improved thanks to decades of the SunSmart campaign and practical changes such as improving sun protection in childcare settings and schools, Professor Lynch says.

But putting the onus on personal responsibility won’t get to the heart of the problem.

“People don’t choose to be unhealthy,” she says.

“Our behaviours are really reflecting the environment in which we live and the social conditions we’re subjected to. Modifying behaviour in any meaningful way requires systems-level change.”

TOBACCO’S TOP BILLING

The main take-away from The Lancet study is that something must be done, and reducing smoking should be our first priority, says epidemiologist Professor Adrian Esterman.

Australia used to be at the forefront of smoking cessation, the chair of biostatistics and epidemiology at the University of South Australia says.

“We were one of the best countries in the world at this,” he says.

“Unfortunately, that slipped over time and we’re falling behind other countries. It’s about time we started ramping up again.”

Professor Esterman wants Australia to follow New Zealand in introducing a policy banning anyone born on or after 1 January 2009 from ever buying cigarettes.

“Eventually they will have a whole generation of people who don’t smoke, which is a fantastic move,” he says.

“It’s innovative, it’s brilliant and one of the best things we could do to lower cancer rates in Australia. Let’s just ban the bloody things once and for all.”

Historical data from as far back as the 1960s suggest each drop in smoking rates corresponded with the introduction of policies like smoke-free workplaces and public spaces, increased taxes, health warnings on tobacco products and Quit campaigns.

Australia has one of the highest costs of cigarettes in the world, but experts debate how useful it is to continue to ramp up costs.

“It’s well established that every time you increase costs you get fewer people who are able to smoke,” Professor Esterman says.

“The trouble is we’re now down to 12% of adults who smoke, and they are the hardcore smokers, and they will smoke no matt er what the cost. They will probably just give up food.”

Anita Dessaix, chair of Cancer Council Australia’s Public Health Committee, says Australian smokers overwhelmingly want to quit, and the way to help those still smoking is through measures that have historically been shown to work.

That includes the graphic images of the damage caused by smoking, which played an important role in encouraging people to quit and preventing young people from taking it up. She says we need to do more on that front.

“One of the big things that’s absent in Australia at the moment is significant investment in national public education campaigns that highlight the harms of smoking and drive motivation for smokers to quit through evidence-based measures,” she says.

TACKLING OBESITY REQUIRES POLITICAL WILLPOWER

Despite the growing awareness of the role weight plays in cancer, we have not approached obesity the same way we did smoking. The number of cancers linked to high BMI have almost quadrupled in Australia in the last four decades, and in young people they have tripled, according to research in The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific.

And this trend may worsen, as research suggests two in three Australian adults and one in four children are overweight or obese.

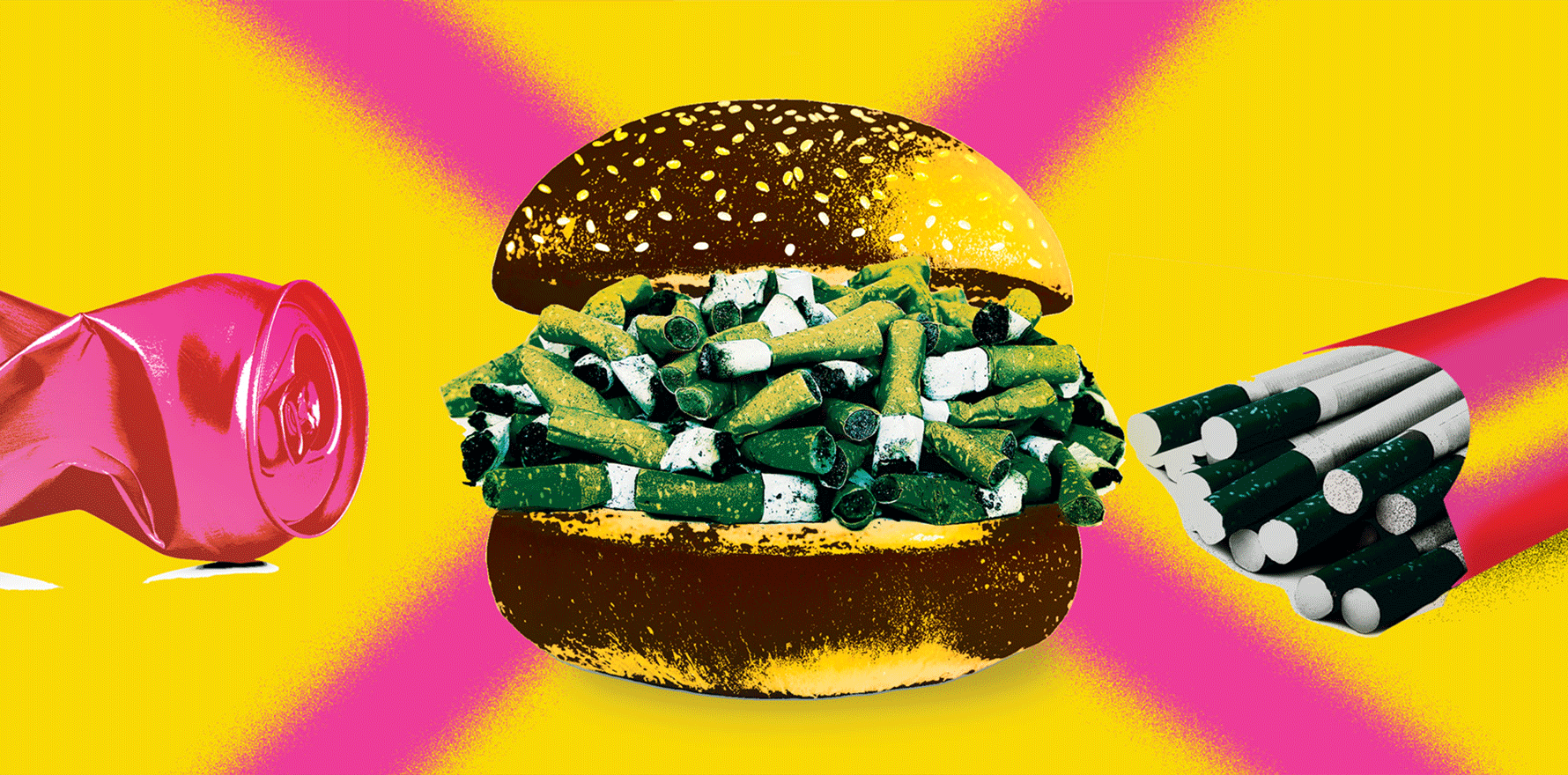

But instead of graphic health warnings on junk food, we get quite the opposite – an environment saturated with junk food marketing, says Jane Martin, executive manager of alcohol and obesity policy at Cancer Council Victoria.

“For children, the promotion of those foods is the wallpaper in their lives,” says Ms Martin, who leads the advocacy group Obesity Policy Coalition.

“There’s more and more processed food on the market. It’s cheap, it’s heavily promoted and it’s everywhere.”

There is a stigma attached to obesity by some in the medical profession, says Ms Martin, but the causes of obesity are systemic; the result of an environment where the processed food industry “has carte blanche to make profit at the expense of people’s health — including very young children — and the government’s just allowing that”.

Unlike more than 50 countries that have introduced a sugar-sweetened beverage tax, Australia does not have any kind of sugar tax, despite decades of campaigning.

Nor do we have controls on advertising like the UK does, where unhealthy food cannot be marketed on TV during peak children’s viewing times and unhealthy food advertising has been removed from digital platforms, Ms Martin says.

It’s these concrete strategies that are needed if we want to reduce the power and influence of industry like we did with the tobacco industry, she says. Australia also needs better referral pathways and a Quitline-style service to actively support patients who are trying to manage their weight, she says.

“We wouldn’t have reduced the road toll or tobacco smoking if we just relied on education,” Ms Martin says.

She is also critical of obesity being framed as a failure of individual and collective will. Instead, population health will only change if we “urgently” implement policies and regulations that act to create an environment supportive of healthy eating and active living, she says.

“Protecting children from the marketing of unhealthy food is something that is recommended in the National Obesity Strategy and the National Preventative Health Strategy,” she says.

“The previous government had set aside in the budget half a million dollars to investigate the feasibility of government controls on unhealthy food marketing, and we’re hoping that that funding remains in the budget after October.”

Ms Dessaix also looks to the NPHS, highlighting its nutrition and physical activity targets as goals to focus on.

“To meet those targets, something has fundamentally got to shift in the space of overweight and obesity,” Ms Dessaix says.

She agrees that Australian governments could be doing much more, backing a sugar sweetened beverage tax, restricting junk food marketing and promoting the importance of healthy eating and physical activity guidelines.

“A really easy thing that almost all state and territory governments could do is to remove junk food marketing on their own government assets like public transport,” she points out.

Some state and territory governments have invested in healthy eating campaigns, but it’s been patchy, Ms Dessaix says. We need to see intervention at a scale on par with smoking campaigns.

“It requires political will and commitment, and the dollars to match,” she says.

Adjunct Professor Karen Price, president of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, agrees that telling patients to exercise more and eat less isn’t enough.

“We’ve got to really ask ourselves hard questions around food labelling and the freedom to choose, and health literacy in young children in learning how to cook their own food and learning how to shop healthily,” she says.

Moreover, Professor Price points out that while weight loss drugs and lap band surgery have been shown to improve health outcomes, they are out of reach for many patients.

“Many people have to go and borrow money or take money out of their superannuation to access it,” she says.

“The new medications are fairly expensive, but we’re hoping to see some movement on that from the government.”

Meanwhile, many clinicians still struggle with the complicated and sensitive nature of weight loss.

“It’s a difficult situation when someone who’s overweight or obese walks in the room because we don’t want to go down the path of fat shaming,” Professor Price says.

“We know that obesity is a very complex problem and has many co-contributors such as childhood trauma. But we do need to talk about it as a risk factor for cancer and for other diseases.

“People have got to be very sensitively approached because they may well have trauma. They’re often in lower socio-economic groups with poor dietary literacy, and they’re time poor.”

PUBLIC UNAWARE OF ALCOHOL CANCER RISKS

Although most Australians have consumed alcohol by the time they’re 14, few are aware of the connection between alcohol and cancer.

Figures from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare show that risky levels of drinking have declined during the past two decades, from around 20% in 2001 to just under 17% in 2019. But we still rate 21st out of 49 OECD countries ranked by alcohol consumption.

Ms Dessaix says some states and territories are taking measures. Western Australia, for example, has banned alcohol advertising on state-owned assets such as public transport. But she says we could be doing a lot better nationwide, by promoting the updated NHMRC alcohol guidelines, restricting advertising of alcohol, especially to vulnerable populations such as children, and instituting a volumetric tax on alcohol.

“They’re three really important ways that we could help reduce harmful alcohol consumption within the community,” she says.

But Professor Esterman believes meaningful attitude change will be hard to achieve.

“Traditionally Australia has been a fairly hard-drinking country. People get pleasure from drinking and for most it’s relatively harmless. I think it will be very difficult for us to reduce alcohol consumption to a large extent,” he says.

The daily challenge of helping patients understand the health risks and modify their behaviours falls largely to GPs, says Professor Price.

“For example, I spend a lot of time educating women in midlife around hormone replacement therapy,” she says.

“I talk about the fact that alcohol is several orders of magnitude more of a contributor to cancer than hormone replacement therapy is for breast cancer, and people are surprised.”

Professor Price says doctors may not realise how much some patients are regularly drinking. High-functioning women with school-aged children, for instance, are one group that can slip under the radar.

“They might be going to the gym and eating well, but they’re also drinking two or three glasses of wine regularly a day and not realising how much that’s contributing to cancer risk,” Professor Price says.

“It’s always good to ask anybody about their alcohol use, because you can make assumptions and those assumptions are likely to be wrong.”