It seems unbelievable that prison could be a healthcare highlight in someone’s life. But the numbers don’t lie; they just hide an uglier reality

Alice* has a son who’s been to jail, an ex-spouse who is currently in jail, and she’s been to jail herself.

She knows the NSW prison health system quite well and has nothing good to say about it.

Her son was in prison for two years and received “no treatment whatsoever” for his severe eczema, she says. His skin was “absolutely appalling … like it was really, really bad … large scales of black crust all over his body”.

Her former partner has spent over 25 years in prison. He was diagnosed with a hernia three years ago and is still waiting to have it removed. It could burst at any time, she says.

“He’s a violent sort of criminal,” she says. “He’s only ever been out for a year or so since he was about 11 years old. His mental health should have been looked at a long, long time ago. It’s just gotten worse over the years.”

When Alice was in custody in Newcastle for a few days, “there wasn’t even a cake of soap”, she says.

“It wasn’t very hygienic. And the prison guards, they look through you as if you’re not even human. I was sort of poked with a baton to move along the hallways. It was very degrading.”

Alice is not alone in giving Australian prisons a zero-star rating for healthcare.

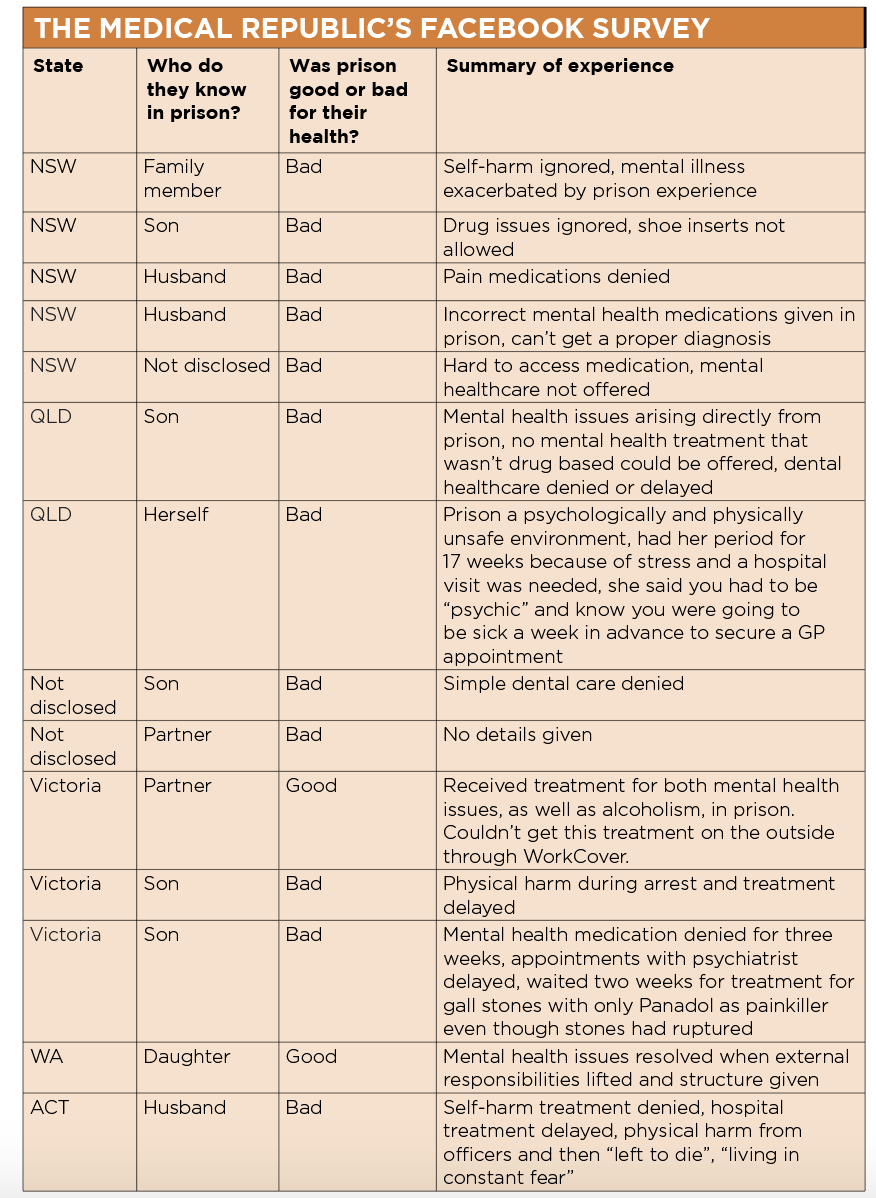

Twelve other family members of prisoners (whom I contacted through Facebook support networks) told me that jail had a profoundly negative effect on their loved one’s health.

“When my son was arrested, he was brutally assaulted by the police and, despite the judge ordering urgent medical attention at his hearing the next morning, it took nine days to see a doctor,” said a woman from Melbourne.

“My husband is currently in the NSW prison system,” another woman said. “His mental health has been a major issue since going in. We can’t get a proper diagnosis and he doesn’t receive correct medication on a regular basis. His mental health has continued to decline.”

“My son had gallstones,” a woman from Victoria said. “He waited for over two weeks to be transferred to hospital. The only pain relief offered was Panadol.”

As a Greens politician in NSW parliament, David Shoebridge makes it his job to take meetings with the family members of prisoners.

“When you talk to parents, it can be quite heartbreaking,” he says.

“Parents know their child has done something wrong. They expect punishment. But they are often very surprised at how utterly indifferent the system is to rehabilitation, how utterly brutalising the experience is for their children. And it’s the same with partners.”

It’s fairly obvious why prison could be a psychologically toxic experience for many people.

In NSW, prisoners are stripped of any normal social support and forced to spend 16 hours a day inside a small prison cell with up to three other inmates. There’s a toilet in the corner and no real privacy.

NSW prisoners get to stretch their legs outside for about eight hours a day but that’s all. It’s a tinder box for fist fights.

“That’s a very unnatural situation,” says Brett Collins, the coordinator of human rights advocacy group Justice Action who has lived experience of prison.

“You become bored, restless. You don’t get the exercise you need. And you have the frustration of having somebody beside you who is not your friend.”

Smoking is now banned in NSW prisons, but around three-quarters of inmates are still itching for a cigarette, he says.

“People who were previously using nicotine can’t use it anymore,” says Mr Collins. “So, now the only thing that’s available is injecting with heroin or it’s ice or it’s whatever you’ve got, sometimes it’s vegemite.”

A hypodermic needle is a valuable commodity in prison and if a prisoner manages to get hold of one, it can get shared around between hundreds of prisoners.

While prison health networks tout their hepatitis C treatment programs as a major success, this drug dependency usually undercuts any gains, says Mr Collins.

“If someone does rid themselves of the virus, they become re-infected because they can’t stop shooting up,” says Mr Collins. “There’s nothing else to do.”

Given this abysmal report card for prison healthcare, you can imagine my surprise when I came across a report claiming prison was actually good for people’s health and wellbeing.

In this report, which was published last year by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, only around 15% of people reported a deterioration in their mental or physical health while in jail.

Around 40% of people surveyed said their mental health improved while incarcerated and over half of people said their physical health improved during their time behind bars.

These statistics seem to contradict those personal narratives, so what’s going on?

When I put these numbers to Mr Shoebridge during our interview at Parliament House in Sydney, he didn’t skip a beat.

“It’s in large part explained by the cohort of people that go into prison,” he said.

“Normally, you don’t find yourself going from a highly stable, engaging, well paid job with strong family support, straight into prison.

“The majority of people who find themselves in jail come from already quite dysfunctional family backgrounds, often chronic poverty, chronic homelessness, major mental health concerns and often living a life that is full of large degrees of uncertainty.

“I mean, it’s a particularly brutal and awful form of stability, but at least they’re guaranteed to have shelter, at least they are guaranteed to have meals for the next week.

“And, tragically, for a fair proportion of people who go to jail that’s the first time to have stability in their lives.”

Mr Shoebridge’s description of jail as a comparatively safe space when juxtaposed against the chaos of life on the outside matches two of our Facebook survey respondents.

“My daughter has suffered from mental health issues throughout most of her life and over the past 11 months since the date of the offence, I have seen her improve in many ways,” said one woman from Western Australia.

“Since she has been in prison the structure and access to education and lack of responsibilities to stay on top of has helped her immensely,” she said. “She is a far different way more balanced and confident person now than she ever was before.”

A woman from Victoria said: “My partner’s mental health has had positive changes since being imprisoned and he himself has stated he is getting the help in there that he needed that he could not get on his own.

“On the outside he had seen five different psychs that said he would need rehabilitation for alcohol and intensive mental help before reengaging in the work force.

“His WorkCover provider just kept trying to move him back into work quicker rather than paying for these. He has made leaps and bounds inside and said the help is there for prisoners if they really seek it.”

(For this story I also requested interviews with the minister and shadow minister for corrections in NSW, as well as the NSW health minister, but only Mr Shoebridge agreed to an interview.)

Professor Michael Levy, the former clinical director of Justice Health Services in ACT who has 25 years of experience working with Australian prisons, says it is “extremely disappointing” that so many disadvantaged people only make contact with medical or social services while in prison.

The prison population is made up of people who have experienced social exclusion their whole lives, he says.

Over half of prisoners were expelled from school; 20% dropped out before year six and the majority left school before year 10 in NSW.

The health of prisoners is some of the poorest in the country; around 63% of the NSW prison population have received a mental health diagnosis and two-thirds enter prison with a daily substance use disorder.

Around 10% were homeless before prison and 17% had an intellectual disability.

“Prisons concentrate people with mental illness, drug dependence, poor housing, unstable housing and poor relationships,” says Professor Levy.

“When people come to jail, and if there is a competent health service, then for the first time in a long time that they have physical proximity to a health service.”

There are, of course, practical difficulties in getting timely care to prisoners, such as the risk that a prisoner will escape if they’re taken to a nearby hospital without heightened security, says Professor Levy.

And sometimes these external concerns get in the way of delivering good healthcare.

For instance, if there were three patients who needed outpatient care in an ACT prison, one with a fracture, one with an eye hemorrhage due to assault and one who was an unstable diabetic, “the custodial authorities might say, ‘We can take two of them, not three’. We have to make what I think is an unreasonable decision,” says Professor Levy.

Prison healthcare is run by state and territory governments. This means that prisoners do not have access to Medicare or PBS-subsidies, which are funded by the Commonwealth government.

“This causes a few problems because, for example, some of the medications that you might want to access for your patients are very expensive for the prison but would have been available to that patient if they were in the community through the PBS,” says Associate Professor Penny Abbott, a GP and researcher affiliated with Western Sydney University who works in women’s prisons.

In NSW, the Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network is run by nurses who triage patients.

There are 16 full-time equivalent GPs across NSW prisons.

That doesn’t sound like a lot, but the rate of GPs to prisoners is pretty similar to the general community (around 859 patients per FTE GP in NSW prisons and around 1,000 patients per FTE GP in the general community).

There’s increasing pressure on these GPs, however, as the NSW prison population has grown 42% since 2011.

The NSW prison healthcare system looks quite busy if you examine the workflow for 2017-18, which included around 27,000 GP appointments, 5,800 flu shots, 1,100 patients treated for hepatitis C, 1,400 hepatitis B vaccinations and 155,000 pathology results.

“It’s clear that people actually physically access care generally more in prison,” says Professor Abbott. “I mean, it’s all there for you. You just put your name on the list, and you get called up.

“I don’t see prisons as a healing place by any means… [But] when you come into prison, you stop using drugs, your head becomes clearer, and you can start to focus a little bit more on your health.

“When you come into prison, you stop using drugs, your head becomes clearer, and you can start to focus a little bit more on your health,” she says.

Professor Abbott works in a medium-to-minimum security women’s prison. I asked her to describe a normal working day.

“I go through a security clearance and then the officer just facilitates me seeing the patients. I have a list that’s been prepared by the nurses.

“The nurses have carefully triaged. For example, they might have tried various creams for a rash, but the rash hasn’t gone away. It’s more complicated than just the standard stuff, therefore the patient is on my list.”

Preventative care is done quite well in NSW prisons, she says. “Women will get their Pap smear screening test, mammograms, blood tests done for blood-borne disease. Hepatitis C is a big one,” she says.

But, of course, the prison health system is far from perfect, and it’s chronically underfunded, says Professor Abbott.

“There are lots of things that are available to people in the community that are not available in the prison health service, which is a travesty,” she says.

There is very limited access to allied health services such as psychology, podiatry, occupational therapy, speech therapy and physiotherapy.

Some prisons in NSW have visiting physiotherapists, but most of the time prisoners are referred to hospitals.

There aren’t many custodial officers to escort prisoners to hospital so most of the seats on the bus are needed for emergency cases.

Sometimes the wait time is longer than the prisoners’ sentence, so the patient leaves prison without ever seeing the specialist.

This is a real pity and “such a waste of money” , says Professor Abbott, because the GP in prison might have done an enormous amount of investigation before referring the patient on.

“It’s hard to get healthcare always done within a sentence,” she says.

Ex-prisoners often don’t take the prison healthcare paperwork to their GP in the community because of the stigma around imprisonment. One prisoner told Professor Abbott that she had thrown her prison discharge summary in the bin for that very reason.

Prison can be damaging to some people’s health, and helpful for others. Often, big issues crop up when people transition in and out of prison, which causes fragmentation in healthcare.

Professor Abbott calls this experience “medical homelessness”, where prisoners feel “caught in a perpetual state of waiting and exclusion during cycles of prison- and community-based care”.

“There is a really quite a high risk of hospitalisation and death after you leave prison,” says Professor Abbott.

“You can imagine if you’re in a controlled environment and suddenly you’re out … you feel lonely, your family’s very angry with you after what you did before you went in.”

*not her real name