The latest cost-cutting change, besides being quite impossible to implement, has some terrible potential consequences.

While another tough year drew to a close, the government quietly attempted to introduce a major change to public hospital outpatient funding, by changing a definition.

The change is intended to reduce the available rebate from 85% of the Medicare Schedule fee to 75%, but is so ignorant and ill conceived, it beggars belief.

A fundamental tenet of Medicare is that there are only two categories of patients: inpatients and outpatients. It is of course more complex than it sounds, especially in the hospital setting, but this has nonetheless been a core feature of Medicare since the scheme began.

But Medicare is apparently now fluid. The change offers a modern, non-binary option for patients, enabling them to be both inpatients and outpatients simultaneously. Exciting! We now have ins, outs, and in-outs!

In July 2021, relevant sections of GN.1.2 of the MBS said this:

“In general, the Medicare benefit is 85% of the Schedule fee” and

“75% of the Schedule fee for professional services rendered to a patient as part of an episode of hospital treatment (other than public patients);”

By December 2021, the following definition of “an episode of hospital treatment” had appeared:

“In general, the Medicare benefit is 85% of the Schedule fee” and

“75% of the Schedule fee for professional services rendered to a patient as part of an episode of hospital treatment (other than services provided to public patients), including services provided in hospital outpatient settings but not generally including services set out in the note below. Medical practitioners must indicate on their accounts if a medical service is rendered in these circumstances by placing an asterisk ‘*’ or the letter ‘H’ directly after an item number where used; or a description of the professional service and an indication the service was rendered as an episode of hospital treatment (for example, ‘in hospital’, ‘hospital outpatient service’, ‘admitted’ or ‘in patient’).”

So, it seems that public hospital outpatient services are now going to attract the lower 75% inpatient benefit, because even though outpatients are out, the new definition supposedly brings them in.

The instructions in GN.1.2 fall short of advising exactly where “on their accounts” doctors should insert the new information, but let’s explore that for a moment.

My company is a Medicare software vendor. Our team of in-house developers therefore have deep experience and knowledge of Medicare’s online claiming infrastructure. They were perplexed.

The first thing the government appears to have failed to understand is how Medicare online claiming works. Specifically, the instructions in GN.1.2 suggest ignorance of one key fact – that the “service description” data field does not transmit to Medicare, and never has. It is for practice use only.

That means that if a doctor does precisely what GN.1.2 says, and writes “hospital outpatient service” where the service description goes, that text won’t go anywhere, so no one will see it. Remember also, that public hospitals bulk-bill, so these are not printed paper claims, it’s all electronic.

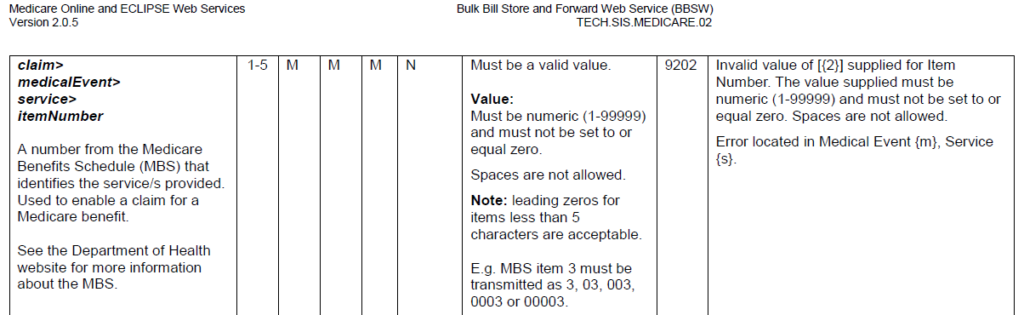

A data element that does transmit is the MBS item number. On Medicare’s old platform it was possible to add alpha-numeric characters like the letter H, but not special characters like an *. So, the advice in GN.1.2 to add an asterisk next to the item number was already impossible.

On Medicare’s new platform, which all software vendors must switch to by March this year, neither special characters, spaces, nor letters are permitted in the item number data field. Below are the specifications.

For abundant caution, we decided to test this out with a willing doctor who was doing hospital outpatient consultations. We first manually reduced the value of a claim from 85% to 75%, and then added the letter H, exactly as GN.1.2 advises. We are on Medicare’s new platform, and the claim would not go, due to the letter H being an invalid value (see below).

So, to summarise so far, the suggestion in GN.1.2 to add an * or H cannot physically be done, and the service description does not transmit.

Additionally, Medicare is the one payer that has always corrected underpayments. This means that if you accidentally underbill, Medicare will adjust upwards and reimburse the correct amount, using reason code 255 – “Benefit assigned has been increased.”

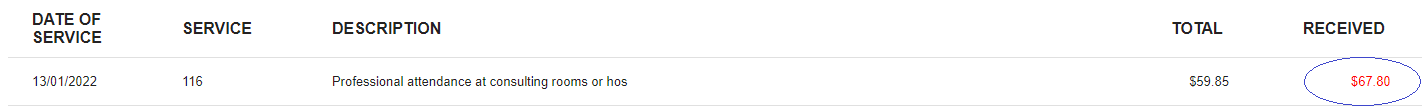

We tested this too. We omitted the letter H and successfully transmitted a claim at 75%, and as expected, it was adjusted up and paid at 85%.

One final option is to enter text in the “service text” data field. This is where billers usually enter things like service times and sites, and this data element does transmit to Medicare.

We predicted this test would also fail, principally because experience tells us that no one reads service text at the other end of claims.

We were right. After again manually reducing the dollar value of a claim to 75%, we added “hospital outpatient service” into the service text field. Medicare returned reason code 255 and again reimbursed the claim at the higher rate of 85%.

The doctor confirmed bank deposits of 85%, or $67.80, on all test claims.

Where all of this leads is deeply troubling. Findings from my PhD made clear that legal literacy around correct use of Medicare is extremely low, and the system itself has become so incoherent that compliance is nigh impossible. This change will not only compound compliance challenges for doctors working in public hospitals, but is a clear example of compliance being literally impossible – you cannot actually do what GN.1.2 says!

Further, if the government now quickly scurries around looking for solutions, things will only get worse, because there aren’t many options. Requiring manual review of service text on millions of claims would cost more than, for example, the $7.95 saved on each item 116. And refunding inadvertently overpaid claims will also solve nothing, because giving money back to Medicare is already an expensive, administrative nightmare.

In fact, the only way we can see that will force the online system to reimburse at 75% is to engage in unlawful conduct. It requires misrepresenting to the government that the service was provided when the patient was formally admitted to the hospital, which is untrue. Such conduct would usually be viewed by lawyers as providing information that is false in a material particular, thereby invoking a possible action in criminal fraud – because it is illegal to bulk-bill admitted public patients. That’s Medicare 101.

The downstream negative impacts of this omnishambles are too many to name, but some of the more devastating are as follows:

- Contracted doctors in public hospital outpatient clinics (OPD) do not provide their services at the hospital. The complex legal nature of their arrangements usually means they provide services in a private room that just happens to be located inside the premises of a public OPD. They pay a licence fee for the room and arguably fall outside the new definition.

- Salaried doctors can simply stop providing OPD services, close their public clinics, and elect to see these patients in their private rooms instead, where they can bulk-bill at 85%. This is already happening, and is worse for consumers because the provisions of the National Health Reform Agreement do not apply in private rooms, so doctors can charge gaps to these “public” patients if they wish.

- The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare will have to completely rework the national definition of a “hospital admission” contained in the National Health Data Dictionary. Anecdotally, it took about five years to reach agreement on the current definition.

- Outpatient episodes are not coded in Australia, but the new in-out episodes will need to be coded to inform and align with the national Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs). Australian coding standards will therefore need to be changed, and every Australian coder will need to be retrained to code the new in-out patient episodes, at great cost to public hospitals.

- The Australian DRGs will need to be recalculated, and the Tier-2 arrangements will need to be reworked to either incorporate, or completely separate, the new in-out encounters.

This whole fiasco is a breathtakingly amateur cost-cutting exercise. It is completely devoid of any understanding of the law, or data supply chain governance. The Medicare billing system is already broken, and non-evidence-based initiatives like this, which are solely focussed on fiscal constraint without considering potential damage to the broader health system, make matters worse.

And to add insult to injury, this will cost more than it will save.

Dr Margaret Faux is a health system administrator, lawyer and registered nurse with a PhD in Medicare compliance, and is the CEO of AIMAC, which offers courses and explainers on legally correct Medicare billing.