Why were the findings of a study of GP paediatric care so strangely interpreted? asks Dr Edwin Kruys

A new national study published in the Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health shows that around 90% of parents are mostly or completely confident in GPs to provide general care to their children.

This is, of course, good news.

The findings also show that 93% of the parents participating in the study reported that they would take their child to see a GP in the event of a minor illness, instead of visiting the emergency department – which is exactly what everyone wants.

Therefore, I was surprised to read the conclusion from the authors, a group of mainly academic paediatric researchers, that “confidence with GPs is an issue for parents of many walks of life” which could potentially lead to “greater numbers of ED presentations for children with lower urgency conditions.”

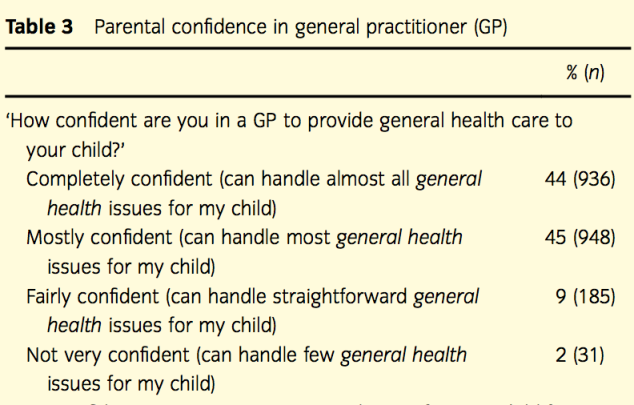

Sorry? The results of the study clearly show that only 2% of parents were not very confident in their GP (see table). I wonder what is going on here.

The authors conveniently omitted the “mostly confident” category (45%) and only reported the “completely confident” category (44%) as their main result, stating that “fewer than half of parents were completely confident” in a GP.

I wonder how many consumer satisfaction studies show a 100% score all the time. The bottom line is that many people inherently have fears when it comes to their own health and especially the health of their children. This may be reflected in their attitudes in confidence of health care services, but this is often a natural fear and as a profession we need to support our patients and address their fears and concerns.

More bizarre conclusions

It appears the authors have a different agenda, as they went on: “Given that GPs in training are having limited experience in child health and that GPs are seeing fewer children overall, more intensive training pathways for paediatric care may be beneficial. One option would be for additional training similar to the certificate for GP provision of antenatal care.”

Additional training? Current GP training already includes childhood conditions as this is core general practice business. GP waiting rooms are full of children and most childhood conditions and preventive health are managed successfully by GPs.

We know that Australia has one of the highest life expectancies in the world, partly because Australian general practice is accessible and offers longitudinal care.

The findings of the study also confirm that parental confidence is greater for those with a regular GP, so instead of providing advice about more intensive training pathways, it would have been useful if the authors had recommended that parents find a regular family GP they trust.

Seeing a GP who is a RACGP Fellow should serve as reassurance to parents that they are seeing a specialist GP who has trained at the highest possible general practice standard in Australia – including child health and antenatal care.

There are of course challenges with doctors coming into GP training in this area. In recent years, the access of junior hospital doctors to paediatric experience in hospitals before entering GP training has decreased. Like all training and learning needs, this is taken into account when supervising GP trainees to ensure patient safety.

Not helpful

If there is some area we need to do better, we need to know that but based on the findings of this study I don’t see a major problem with the paediatric care provided by Australian GPs.

My take-home message from this study is first of all that this style of reporting research findings is, at best, not helpful.

Secondly, the study clearly demonstrates the need for quality research in general practice, in terms of improving access to high value treatments and the appropriate use of limited health resources.

Dr Edwin Kruys is a Queensland GP. This blog was originally published on Doctor’s Bag.