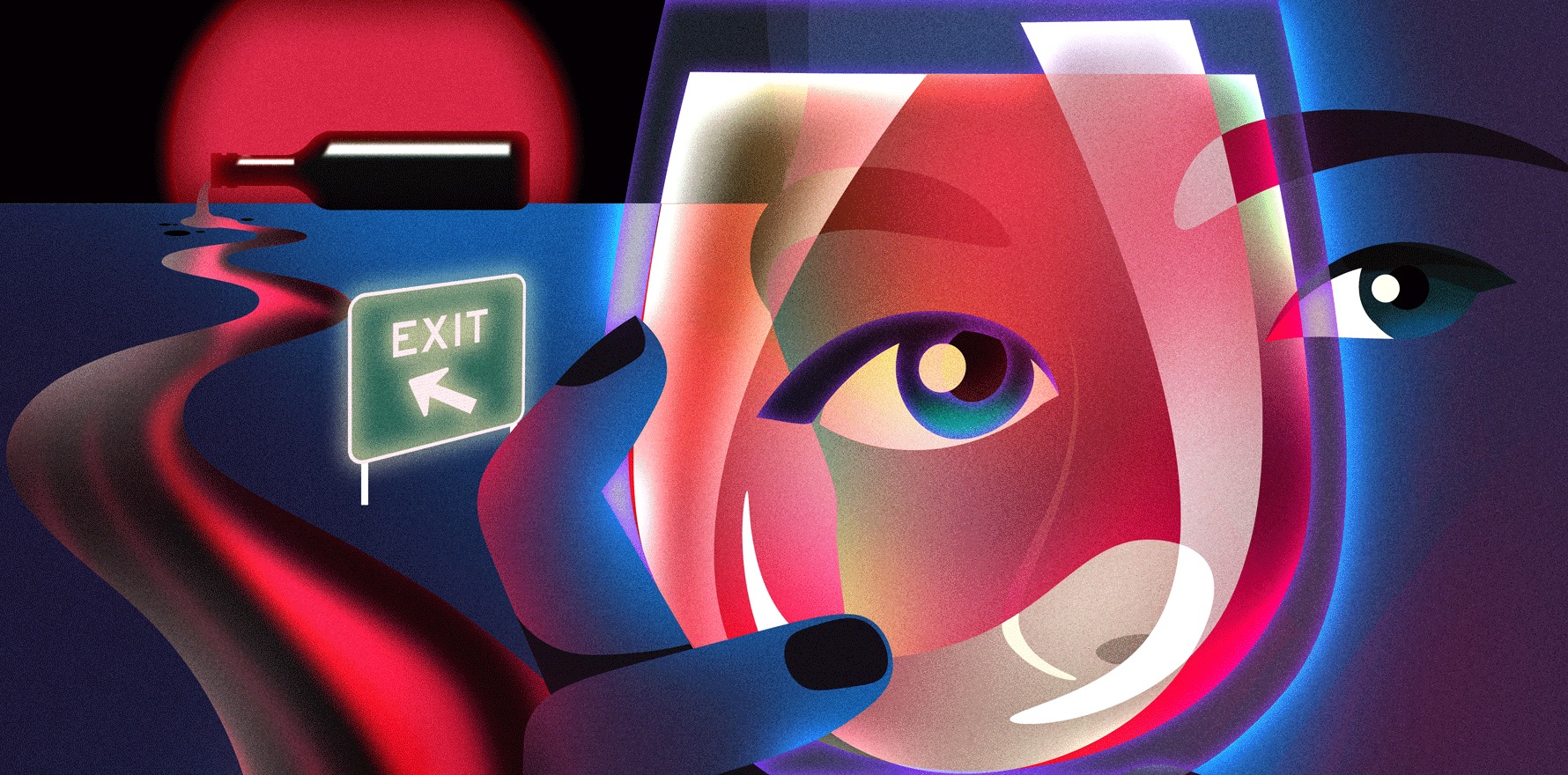

There are many pressures to quit medicine, but for those prone to substance use it can be a jump from frying pan to fire.

Lately I’ve noticed that many of us are talking about early retirement. This is possibly due to post-covid fatigue or Medicare politics and funding frustrations or both.

Surely an end to the grind would be marvellous. But careful what you wish for. Retirement can be a major existential crisis.

The good news is that there is a certain spiritual alchemy that comes whenever an existential crisis is successfully surmounted. The liberal arts wax lyrical in this space. In the 1991 movie The Doctor, William Hurt stars as ace surgeon Jack McKee. Jack is emotionally disconnected from everyone, patients and family included. Then he develops a life-threatening condition causing him to morph into a human. The lucky have multiple such transformations, thus ever growing their humanity.

I checked into rehab recently. I felt the need for a spiritual retreat. My inner weathervane was whirling alarmingly. See, I’m headed towards retirement, or rather, retiring to my next gig, and wanted to be in the best shape for this, possibly my last, metamorphosis. I’d had prior experience with a similar sanctuary about 30 years ago, and I had greatly benefited from a master class in self, or more particularly, subconscious-self-enlightenment. Carl Jung mused: “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

This time I did feel like a bit of an impostor. During the intervening years between rehab stints, I had the benefit of over a decade of abstinence before I resumed drinking in moderation. At times a little more than I intended. For comparison, in Queensland according to its Alcohol and Other Drugs Plan, one in three adults in the general population (1.2 million people) exceeds single-occasion risky drinking monthly.

Upon checking in, I was asked how long it had been since my last drink. I truthfully answered six weeks. Were there any other drugs of concern? Yes, cannabis. When did you last use? Over 30 years ago. But I knew that many resumed an unhealthy relationship with substances in retirement.

For the purpose of context, half a lifetime ago, fate had me attempt to mix perfectionism, an unhealthy work ethic, emotional over-sensitivity, vicarious workplace-based traumas, a stoic can-do bravado, a grief reaction to my mother’s preventable death and sleep deprivation. I had sailed into a perfect storm and buckled under the allostatic load. I had also had a rather chequered relationship with alcohol and using it as medication did not help.

My relationship with alcohol started at university. I’m not sure if the prevalence rates are the same now but in the mid-70s, half of the student cohort had an unhealthy relationship with booze. Students from the medical faculty were no exception. Besides, we were fed a regular dose of the TV series M*A*S*H*. This constituted our informal curriculum in Medical Professionalism. Surgeons Benjamin “Hawkeye” Pierce and “Trapper” John McIntyre were our role models. Work hard and party hard. Those in my social sphere did both.

My thoughts today are these. Our beliefs are generally based on our values, which in turn frame our behaviour. In Australia, for example, a national belief is that following a hard week’s work, we are entitled to a “party”. A party neurologically equates to inducing a dopamine dump. In “genteel” society that would be sought via booze. Downtown (or uptown) that could be via cocaine, cannabis, prescription opioids etc. In other words, cultural conditioning based on our very human need to self-soothe. And in the beginning alcohol and other drugs are a sure-fire way of satisfying our subconscious dopamine pig.

Now I’m acutely aware that the human brain is an inference-making machine. So maybe I’m retrofitting time-corrupted facts, but … the very first time I got “really high” on an alcohol beverage, I just loved it totally. For me it was an immense inwardly creative bliss providing an almost sacramental vision, the likes of which I had never experienced before. But why was it so?

I presume it was because I was transported to an exceedingly comfortable and arresting place, much like the White Rabbit hole in Alice in Wonderland. It tweaked my curiosity and imagination. From as early as I can recall, I fervently enjoyed creative daydreaming. The sensation was like that, only ramped up to a brand-new level. What followed was many years trying to replicate that. How was I to know it was a once only, never to be repeated “gift”? Shame that it’s an easy spiritual shortcut that turns into a dead-end street. For me the return on investment from alcohol had turned to red. For that reason, all those years ago and on the advice of my psychiatrist, I commenced actual antidepressant medication and stopped drinking booze.

Inspired by new curiosity and a search for meaning, I embarked on a new career path in addiction medicine. On this new path, my patients taught me that what some call addiction is simply the opposite to connection. They also taught me an abundance about humanity and transformation.

Enough of this detour, let’s return to retirement.

As I flagged at the start of this article, retirement is a major transformation. It’s a time for disconnection, celebration and forming new connections. My recent concern was that this potential stressor a.k.a. existential crisis could unleash the wine witch or dopamine pig that I had held at bay while still practising. What might be the consequences when every night is a Friday night? As earlier indicated, it was precisely because of these concerns that I checked myself into rehab. A preventive measure if you will. Like getting the Hilux checked before a desert expedition.

Dame Clare Gerada, President of the Royal College of General Practitioners who has professional interests in mental health and substance misuse, presented at the International Society of Addiction Medicine Conference in Malta last month, which I attended. According to the author of Beneath the White Coat: Doctors, Their Minds and Mental Health, prevalence rates of substance use disorder among doctors is today (as always) difficult to pin down. However, her best bet is between 10-15% of the profession with a confidence interval of 5-30%. After all medicine is a hard taskmaster and is intellectually, physically, and emotional demanding. Those with an unhealthy relationship with alcohol are among us sheltered in plain sight because they remain high functioning. Most are highly disciplined and likely able to “keep a lid on it” while engaged in work.

I suspect that the nature of that lid is complex. There used to be a joke that “you’re only an alcoholic when you drink more than your doctor”. After all, a doctor would surely know when to get help. But do they? Stigma amid the profession is still rife due to prevalence of a humanist view which makes a binary distinction between rational, volitional individuals and compulsive substance users. You either are or are not an alcoholic. But where is the line? Some make the argument that the ICD or DSM categorisations are themselves a spectrum and that their main purpose is to inventorise human conditions for the purpose of billing or research. But that purpose recedes in the real world. That’s why I try to avoid the terms “alcoholism” and AUD in favour of the phrase unhealthy relationship.

The post-humanist view sees individuals as coexisting in a nexus of contingent and dynamic relationships. This ethnographic interpretation begs the question whether the condition is a disease at all. If it is then it’s an anomalous one. It has a major social network dimension and requires therapy for family and significant others to optimise outcomes. What other diseases have equally inspired philosophers, theologians, literati and sociologists as well as physicians and neuroscientists? The public health gurus at the WHO even get in on the act, describing alcohol as a toxic substance. By this definition, all who consume alcohol have an unhealthy relationship with it. But let’s not be total wowsers.

As I left my spiritual retreat, my psychiatrist casually mentioned that it was far more common to admit doctors who were 18 months or more into their retirement. He was glad that I had come while still “well”. He too alluded to studies that have found that retirement leads to increased alcohol consumption and that alcoholism can rapidly advance in this age group.

My hope is that we all remain present and connected in retirement. An unhealthy relationship with alcohol can be undone. Alcohol use disorder, or whatever you wish to call it, is a potentially life-threatening but also a treatable condition.

As doctors, my generation, the Baby Boomers, worked and partied hard. After the work is over, will the party go on and could it get out of hand?

Associate Professor Kees Nydam was at various times an emergency physician and ED director in Wollongong, Campbeltown and Bundaberg. He continues to work as a senior specialist in addiction medicine and to teach medical students attending the University of Queensland Rural Clinical School. He is also a poet and songwriter.