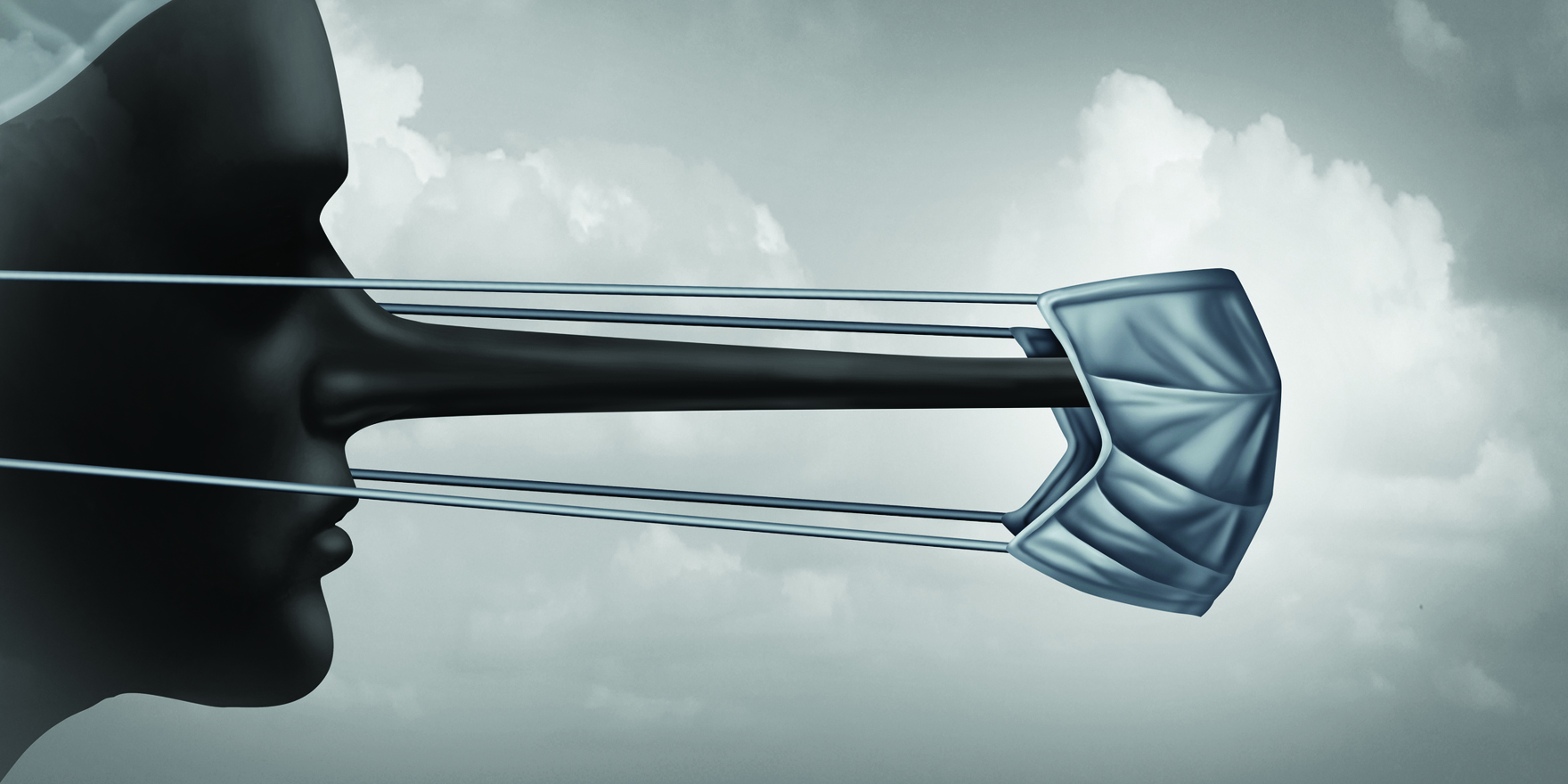

Potentially dangerous stem cell treatments are being marketed under the guise of legitimate clinical research

If you sign up to a clinical trial, you may think whatever treatment you’re getting has been signed off on by an ethics board and has at least passed some safety and efficacy tests.

But when it comes to stem cell treatments, you may be being misled.

In Australia, and worldwide, stem cell treatments have been marketed as a cure for everything from autism to dementia, and websites adopt the language and trappings of science to lead patients into thinking the approach is part of mainstream medicine.

Some clinics are going so far as to register seemingly legitimate trials on the US government-run database, ClinicalTrials.gov, to recruit customers then charging them thousands of dollars for the service.

Ironically, the public clinical trial registry was created in 1997 to increase transparency around research, in part by declaring the scope of a trial at the outset in order to prevent modifying the outcomes afterwards. But it is often also used by patients and clinicians to find trials they may be eligible for.

It turns out this free and relatively unmonitored database can also be a good way of advertising unproven and potentially dangerous treatments under the guise of legitimate clinical research.

Unlike legitimate research however, these trials demand money for the therapy and often never publish clinical data in peer-reviewed journals, instead choosing to only publicise positive anecdotes.

One of these clinics with registered trials on the government database was behind the high profile cases where three of its patients went blind or had severe vision loss after having stem cell therapy for age-related macular degeneration.

Clinical trials are just one of the “tokens of legitimacy” that Canadian health law expert Professor Timothy Caulfield says clinics use to portray themselves as being part of the medical establishment and exploit the trust customers have in science and scientific institutions.

Others include renting space in, or near, universities and hospitals to increase their appearance of legitimacy.

“The other thing these clinics are doing is using predatory journals to make it look like they’re publishing in this space,” the Canada Research Chair in Health Law and Policy explained.

“So when you have a website that has a clinical trial registered on it and that looks like they have publications, it becomes really difficult to tease out the real stuff from the fake stuff.”

Even crowdfunding campaigns are contributing to misrepresentation, according to a study published in the journal, Regenerative Medicine, last week.

Across 78 different campaigns, which raised around half a million dollars for stem cell treatments, campaigners commonly described the treatment as being part of a clinical trial, sometimes even calling them “government-approved clinical trials”.

Campaigners often believed their participation would contribute to the scientific literature and benefit thousands of future patients, the authors reported.

These shoddy practices were under the magnifying glass at the EuroScience Open Forum in Toulouse last week, where experts revealed the tactics clinics are using to manipulate customers into believing the treatments have more mainstream acceptance in the medical community than they really do.

Hyping up the possibility for cure and downplaying or omitting the risks is commonplace both in the media and in the industry itself.

Professor Ana Iltis, at the US center for Bioethics, Health and Society at Wake Forest University, said one way to describe this was that “stem cell clinics are providing incomplete, slanted and sometimes even false information to get people who are in need of treatment to agree to do something that puts them at physical risk and that costs them a great deal of money”.

“It involves an unfair taking advantage of their need and lack of knowledge, and deceives them for the clinic’s gain.”