Bariatric surgery is recommended for the management of morbid obesity. So what are the options?

In Australia, over 60% of adults are either overweight (BMI 25 to 29.9) or obese (BMI>30).

This figure is higher than 25% in children and adolescents, and if current projections continue, by 2025 the figure for adults in Australia will be close to 80%.

This figure is higher than 25% in children and adolescents, and if current projections continue, by 2025 the figure for adults in Australia will be close to 80%.

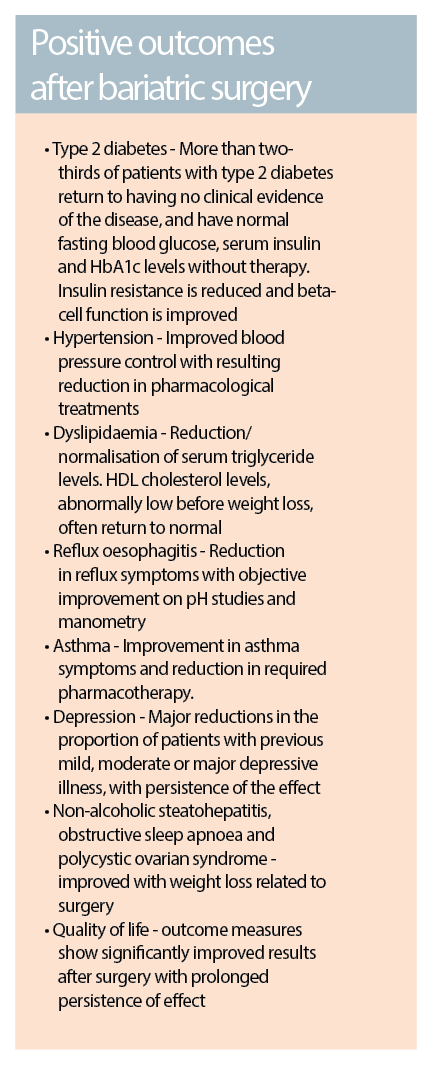

The myriad of established health complications associated with obesity now include Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, dyslipidaemia, sleep apnoea, osteoarthritis, and certain types of cancers, along with an overall reduction in quality of life. In 2000, 44% of people with diabetes in Australia were identified as obese.

Approximately 7.5% of the total burden of disease in the population can be attributed to excess body weight, with an effect lower only than hypertension and tobacco use.

Excess body weight is the highest contributor to the burden of disease in the 35-44 age group (8.6%) and the 45-54 age group (13%). From an economic perspective, the management of obesity-related health issues is a significant financial burden, with the direct costs of obesity recently estimated at over $8 billion per year in Australia.

While there are wide-ranging opinions as to the cause of this “epidemic”, the evidence is often weak and the aetiology of obesity remains multi-factorial and poorly understood.

As well as the interaction between people and their own environments, it is likely that strong genetic and developmental factors contribute to weight gain, in addition to more recently recognised complex physiological factors that may prevent weight loss. These factors also complicate strategies for management.

When is surgery considered?

The NHMRC Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults, Adolescents and Children in Australia (2013) set a framework for GPs, along the following principles:

• Ask and assess

• Advise

• Assist

• Arrange

When excess body weight in a patient has been identified, three main interventions are available – lifestyle modification through decreased energy intake and/or increased energy expenditure, pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery.

The choice of intervention for each person depends on several factors, but is largely based on their baseline BMI and the presence of co-morbidities.

Recent NHMRC guidelines suggest that bariatric surgery, when indicated, should be included as part of an overall clinical pathway for adult weight management delivered by a multidisciplinary team.

Recommendations advise that bariatric surgery should be considered for the management of morbid obesity(BMI >40) or a BMI over 35 in the presence of co-morbid conditions that may be ameliorated by weight loss. It is often considered after failure of lifestyle modification or pharmacotherapy.

For patients falling into the category of “super-obesity” (BMI>50), bariatric surgery is considered a first line option.

Other patients with a BMI under 35, but with significant co-morbidity or complicating factors, may still benefit from surgical intervention and/or referral to a multi-disciplinary unit.

Surgical options for the management of obesity can broadly be divided into two categories:

Restrictive procedures

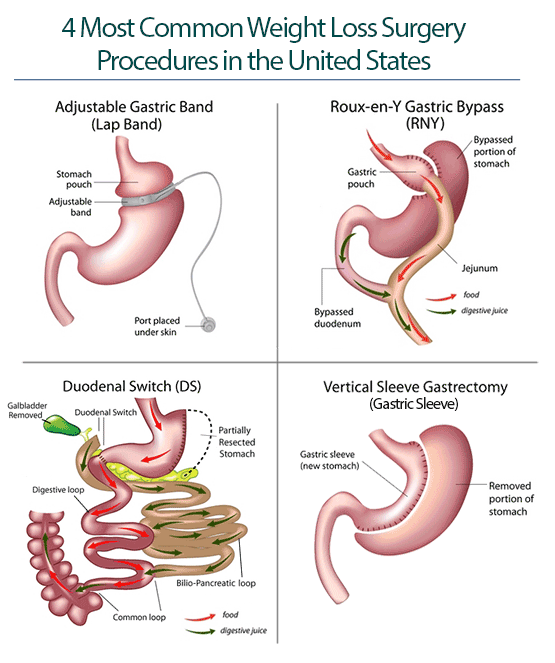

Where the volume of the stomach is reduced leading to early satiety. These are the most commonly performed bariatric procedures, due to their relatively straightforward nature and low complication rates. Procedures include gastroplasty, laparoscopic gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy.

Gastroplasty was first described by Mason in 1982, and is essentially a vertical stapled banding procedure resulting in a narrow stomach tube with limited volume. The main advantages of this procedure are that it often results in rapid weight loss and continues to allow easy diagnostic endoscopic access to the stomach. However, there is a significant relapse rate due to disruption of the staple lines or dilatation of the pouch. This option is now rarely used.

Gastric banding was introduced by Kuzmak in 1986, and involves the placement of an adjustable silicone band below the oesophago-gastric junction, with tubing attached to a subcutaneous chamber. This can be externally accessed and filled with saline to allow adjustable gastric restriction. A small gastric pouch is created and the band sutured in place to prevent slippage. This is easily carried out using laparoscopic surgery and is a relatively straightforward procedure, hence it is one of the most commonly performed bariatric procedures.

Sleeve gastrectomy is a more recent restrictive procedure and involves removing a large portion of the stomach, leaving a tube-like remnant with an approximate volume of 100-120ml. The weight loss caused by this procedure may not only be due to the reduced stomach volume, but may also involve hormonal pathways that are not yet well understood. Due to its relatively recent introduction, long term safety and efficacy data is not yet available.

Malabsorptive procedures with restriction

Where part of the intestinal tract is bypassed thereby reducing the absorption of food, often also incorporating a degree of stomach restriction or volume reduction.

Several different procedures fall into this category, though all are variations on a theme. The basic principle is that an alimentary channel is created where food passes to the small intestine without being exposed to bile or pancreatic secretions. A bilio-pancreatic channel is created, which then delivers biliary and pancreatic digestive juices much further along the intestine.

These channels combine to form a common channel, where ultimately food mixes with the digestive enzymes, usually a lot further along the length of the small intestine than normal, thereby reducing the amount of food that is absorbed through the gut. Examples are: gastric bypass procedures (Roux-en-Y), bilio-pancreatic diversions and duodenal switch procedures.

Gastric bypass procedures: (Roux-en-Y) were first considered for the management of obesity by Mason in 1966 after the observation of weight loss in patients who had undergone a Billroth II gastrectomy for peptic ulcer disease. It essentially involves creating a gastric pouch with a volume of approximately 30-50 mls by “disconnecting” a large amount of the stomach as in a gastrectomy, though the remnant is left in place.

The procedure creates a 45-75 cm alimentary channel and alters the gut hormone profile by exclusion of the stomach, duodenum and proximal jejenum from the flow of ingested food. This is the most commonly performed diversionary procedure.

Biliopancreatic diversion: This was described by Scopinaro in 1976 and involves a 250cm alimentary limb anastomosed to 200-500ml gastric pouch, formed from the proximal stomach after a partial gastrectomy procedure, while the proximal small bowel becomes the biliopancreatic channel and is anastomosed to the terminal ileum 50cm from ileocaecal valve. This results in a significant level of malabsorption due to the diversion and only a very short residual common channel.

Duodenal switch procedures: This procedure, first described by Demeester in 1987 and modified by Hess with a 75% longitudinal gastrectomy, involves a similar process to biliopancreatic diversion, though the common channel is approximately 100cm long, while the alimentary channel consists of 40% of the total length of the original small intestine. The main difference is that rather than forming a pouch from the proximal stomach, the switch procedure involves an anastomosis of the alimentary channel just distal to the pylorus, while a sleeve gastrectomy is also performed.

Outcomes

When choosing which procedure to use, factors such as surgeon experience and local adherence to guidelines play a big part. In general, outcomes are usually better when performed by surgeons in high volume centres, with specialist multi-disciplinary teams providing high quality surgical, anaesthetic, critical care, nursing, dietetic and physiotherapy support.

The choice of procedure may also be impacted by the needs of the individual patient.

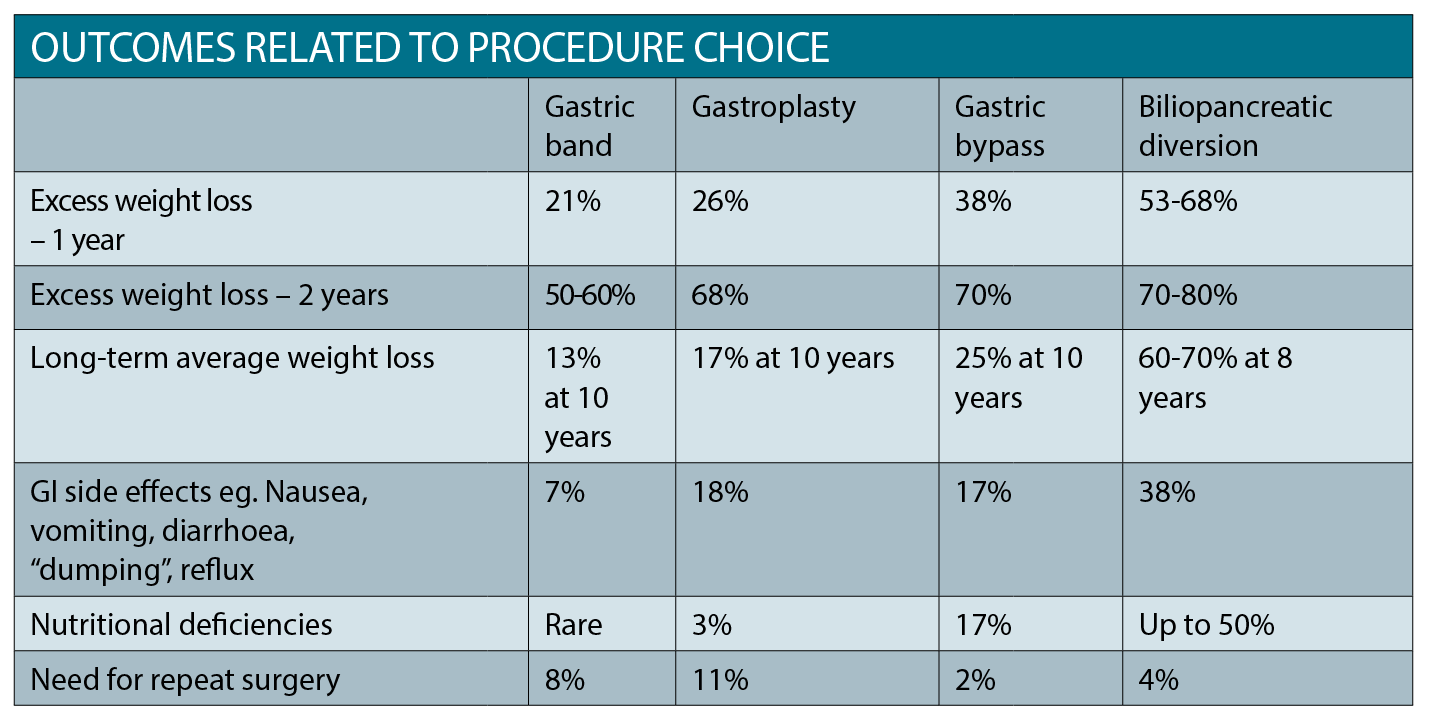

In general, restrictive procedures are easier and have fewer complications, but result in less profound and sustained weight loss.

Bariatric surgery has been shown in many studies to be superior in reducing adverse health outc omes related to obesity compared to all other interventions.

The malabsorptive options are associated with excellent levels of sustained weight loss, but may also be associated with greater nutritional deficiencies.

Despite some significant downsides, including potential high short-term costs and the lack of availability of surgery, weight loss after surgery can have a major positive impact on health and quality of life. Bariatric surgery has been shown in many studies to be superior in reducing adverse health outcomes related to obesity compared to all other interventions.

Adverse effects

While bariatric surgery has been shown to have positive results, as with any surgical procedure, there are a number of potentially serious complications. These include the general peri-operative risks of general anaesthetic in surgery for the obese patient, infection, venous thromboembolism, haemorrhage and even death – the risk of death in hospital after having any form of weight loss surgery is around 1 in 1,000. Risk factors that increase the risk of death after bariatric surgery include age over 45, BMI over 50, male gender, hypertension and other risk factors for VTE.

Over the longer term, other specific problems may arise, depending on which type of procedure has been performed.

• Excess skin: Bariatric surgery reduces the amount of fat in the body, but the skin does not necessarily shrink or revert to its pre-obesity tightness and firmness. Excess folds and rolls of skin, particularly around the breasts, abdomen, hips and limbs may result, becoming most apparent 12-18 months after surgery. Apart from the aesthetic problems this can cause, the skin may be difficult to keep clean and may be vulnerable to rashes and infection. Plastic surgery to remove these excess folds is in itself a major procedure with its own morbidity, and can result a less than ideal cosmetic outcome. It can also be expensive for the patient.

• Gallstones: Around 1 in 12 people develop gallstones after weight loss surgery, typically about 10 months after surgery, and patients may require further surgical management.

• Psychological effects: Most patients report an improvement in their quality of life after surgery, however rapid weight loss an also be related to several adverse psychosocial events. For example, relationship problems can result from patients or their partners feeling nervous, anxious or possibly even envious about their weight loss. Patients may feel self-conscious about their reduced capacity to eat, which may affect their enjoyment of social activities. It is not uncommon for patients who have undergone surgery to experience a worsening of mood when their weight stabilises, typically two years after surgery. This can also be because many people realise that some of their problems that existed before surgery, which they originally attributed to their obesity, remain despite the major upheaval they’ve experienced.

• Stomal stenosis: As many as one in five patients who’ve undergone a gastric bypass develop a stomal stenosis, whereby the stoma connecting their stomach pouch to their small intestine becomes incompletely or completely obstructed. The most common symptom of stomal stenosis is persistent vomiting. Stomal stenosis can be treated by endoscopic balloon dilatation.

• Gastric band slippage: Gastric band slippage is a complication affecting around 1 in 50 people with a gastric band. As the name suggests, the band slips out of position, resulting in the stomach pouch becoming bigger than it should be. This can cause symptoms such as reflux, nausea or vomiting. Further surgery may be required.

• Gastrointestinal disorders: Around one in 35 people with a gastric band develop a food intolerance, for example to red meat or green salad, often many years after their surgery, resulting in symptoms such as nausea, reflux or bloating. The reason behind this is unclear. Aside from intolerances, some patients develop chronic diarrhoea, flatulence and altered stools that can be very debilitating.

When choosing which procedure to use, factors such as surgeon experience and local adherence

to guidelines play a big part.

• Nutritional deficiencies: Lifelong vitamin and mineral supplementation is recommended after all bariatric procedures. The degree of deficiency is likely to be affected by the type of surgery. For example, gastric band procedures do not directly cause a change in mineral or vitamin absorption, but may result in dietary changes that do. While sleeve gastrectomy does not directly lead to malapsorption, nutrient utilisation may be affected, resulting in decreased uptake of iron and vitamin B12. Bypass procedures often result in significant malabsorption-type nutritional deficiencies, and these patients require lifelong supplementation of a variety of vitamins, minerals and trace elements, with doses often needing to be guided by blood testing of levels. If not monitored and treated, the deficiencies may lead to complications including osteoporosis, hair loss and anaemia.

Conclusion

One of the largest investigations into the outcomes of patients after bariatric surgery has been the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) Trial. This study started in 1987 and involved 2010 obese subjects who underwent bariatric surgery – gastric bypass (13%), banding (19%) and vertical banded gastroplasty (68%). These patients were matched against 2037 obese controls receiving usual care.

Over the course of the study, the mean changes in body weight after two, 10, 15 and 20 years were 23%, 17%, 16% and 18% in the surgery group as compared with 0%, 1%, 1% and 1% in the control group.

In the study, bariatric surgery was also associated with a long-term reduction in overall mortality, along with decreased incidences of diabetes, myocardial infarction, stroke and cancer.

The findings, supported by other research, show that surgery is the only obesity treatment resulting in more than 15% average documented weight loss over 10 years. And while the risks of surgery are potentially significant, they are overshadowed by the impact of untreated obesity on health.

As weight-loss techniques are refined, patient selection improves, and peri-operative care optimised, bariatric surgery will likely become a more widely accepted and practiced intervention in the battle against obesity.

Dr Rajwinder Nijjar, FRCS is Consultant Upper GI and Bariatric Surgeon, Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust, UK

References available on request