Who is required to be “professional”? NSW psychiatrists highlight a broken system by threatening to walk away from it. Perhaps it’s time to hold institutions responsible for bad outcomes.

Medical error management has changed significantly throughout my career. It is now well recognised that healthcare systems are safer if the responsibility for an error is examined across the whole system, rather than focusing on an individual failing as the root cause.

Clinical incident debriefing has become normalised across healthcare and has been accompanied by shifts in governance as well as changing expectations in individual practice.

The major shift has been a shift from blaming individuals to sharing responsibility to prevent future harm.

Recent developments in healthcare policy have made me think about where our professionalism responsibilities actually lie. Over time, AHPRA has expanded what is expected under our code of conduct and, in my view, many of the requirements seem to be quite aspirational.

Professionalism as a virtue and a community expectation

We know that the gap between a written policy and “the way we do things around here” is directly proportional to the moral distress health professionals experience.

For instance, many of us as interns had hospitals that stated clearly their commitment to care for their staff. Nevertheless, the unpaid and increasingly unsafe overtime hours were justified by the argument “you need to be more efficient, rather than doing overtime”.

At the time, most of us, with our type A perfectionist personalities, accepted this and tried to work at Olympic speeds, committing ourselves to a goal of “faster, higher, stronger”.

Of course, it didn’t work. Because if you want someone who is that efficient, you don’t employ an intern.

In my view, the best definition of professionalism is that the professionals increase trust in healthcare.

The question is, who is responsible for that trust, and who is held accountable for unprofessional conduct?

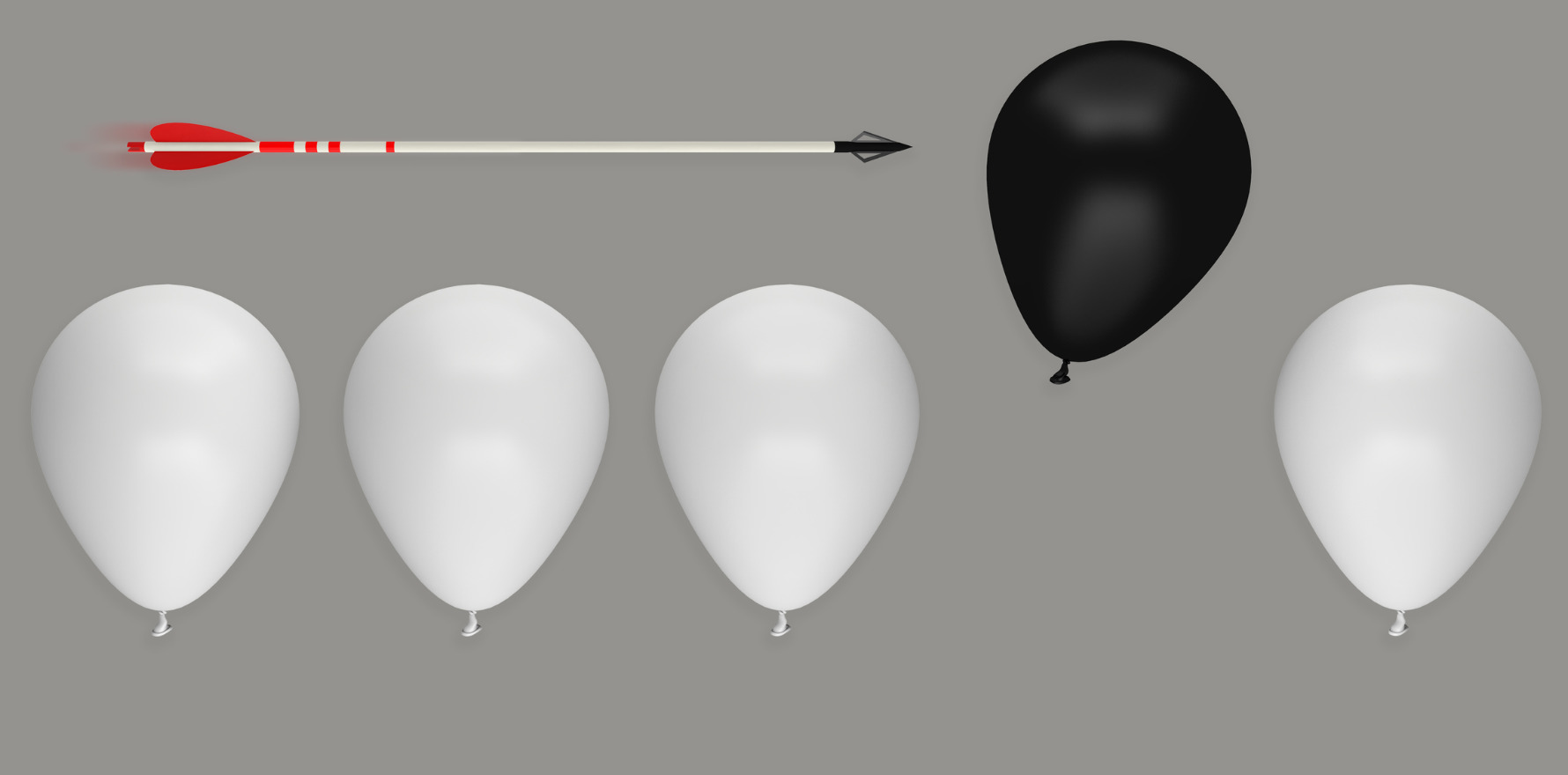

It is easy to simplify a situation where a health professional behaves badly, and think there are “bad apples”, rather than a “bad orchard”. However, people can behave badly for a variety of reasons.

Like medical error, lapses in professionalism should be considered holistically. This does not mean ignoring the individual, but it does mean considering all the factors that have contributed to the behaviour and holding each actor that has contributed to the problem accountable for their actions, policies and motivations.

In my view, one of the best examples of the way this holistic view is abandoned in professional misconduct cases is the case of Dr Hadiza Bawa-Garba.

Dr Bawa-Garba was a paediatric registrar in the UK who was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment for gross negligence leading to the death of a child. Her licence to practice was also suspended by the Medical Practitioners’ Tribunal.

However, the context of this misconduct is important.

Dr Bawa-Garba had already worked a 12-hour shift on her first rotation in paediatric emergency after a return from maternity leave. Her supervising consultant was off-site, and she was covering for at least one other registrar, who was on leave.

The IT system was also down, leading to a delay in accessing blood test results.

More concerning was the use of her reflective journal, which was used to make a case against her in court. Reflective practice is a core professional practice, recommended in medical codes of conduct, to promote life-long learning. In this case, it was weaponised to prove her culpability in court.

Fortunately, Dr Bawa-Garba won her case on appeal, with significant support from her international and local medical colleagues, but it is a staggering example of the scapegoating of a junior clinician working in an under-supported, under-resourced environment.

“Bad orchards” will inevitably lead to some “bad apples”.

Bad orchards: the role of organisations in professional lapses

Codes of conduct have expanded over time to incorporate elements that are difficult to define, and often impossible to implement by individual practitioners alone. There are significant double binds for doctors.

Let’s take the example of the overworked intern and, taking into account the recent crisis in psychiatry, assume that this intern is required to manage things that are well above their pay grade without adequate support.

I am imagining an intern who is expected to assess a patient’s suicidal risk, and, predictably, gets it wrong. In the current environment in NSW, they are unlikely to have access to appropriate supervision, and they are likely to be very, very tired.

Of course, the institution will claim they “should” have accessed appropriate supervision, but we all know “the way we do things around here” is not to disturb the exhausted registrar, and certainly not to ring the consultant.

Related

Given they are highly unlikely to have the institutional power to refuse to take on that responsibility, they run the risk of failing to meet the following expectations in the AHPRA Code of Conduct.

- 3.2.1 Recognising and working within the limits of your competence and scope of practice.

- 6.3.2 Taking reasonable steps to ensure the person to whom you delegate, refer or handover has the qualifications, experience, knowledge and skills to provide the care required.

- 6.3.3 Understanding that when you delegate, although you will not be accountable for the decisions and actions of those to whom you delegate, you remain responsible for the overall management of the patient, and for your decision to delegate.

- 8.1.2 Taking all reasonable steps to address the issue if you have reason to think that patient safety may be compromised.

- 9.2.2 Ensuring that your practice meets the standards reasonably expected by the public and your peers.

- 8.3.1 Recognising and taking steps to minimise the risks of fatigue, including complying with relevant state and territory occupational health and safety legislation.

- 11.2.6 Recognising the impact of fatigue on your health and your ability to care for patients, and endeavouring to work safe hours wherever possible.

So if there is a bad outcome, how much responsibility does the organisation hold, and how much is displaced onto the intern?

Holding organisations responsible for professionalism misconduct

There are number of ways organisations play a role in facilitating misconduct:

- Administrative harms occur when there are barriers to care that prevent a clinician accessing appropriate management. An example is where a diagnosis is delayed because GPs are prevented from ordering appropriate investigations, or insurance companies refuse to fund appropriate care.

- Managerial harms occur when employees are under-resourced, and required to manage patients that are not within their expected scope or where good care is impossible due to workforce constraints. Another example is using the “educational bandaid” – taking a problem and assuming a mandatory course will fix it. Expecting clinicians to prop up a broken system and take responsibility for the inevitable harms is inappropriate.

- Educational harms occur when the curriculum doesn’t meet the expectations placed on learners, or learners are provided inadequate or abusive supervision.

- Regulatory harms are well documented, with many doctors suffering unnecessary harm during the AHPRA process.

- Political harms include scapegoating clinicians. Raising expectations in the public discourse without raising the capacity of the clinicians to deliver them causes harm, because expectation management falls on clinicians, not the policy makers who designed the system. There are also political “double binds” – an example is the public criticism of “medical misogyny” while under-funding the longer consultations required to deliver better care to women.

Addressing institutional misconduct

The governance of organisations is held separately to the system of medical regulation. Therefore, the role of the institution is not always considered when a clinician provides care that is below accepted professional standards.

The NSW psychiatrists have decided the risk is too great.

They say they are unable to provide the care that their patients deserve, and by remaining in the system where they cannot provide adequate care and they are enabling institutions to continue to blame individuals, rather than take responsibility for a broken system.

At the same time, NSW Health, in its strategic documents states the following:

“Clinical safety is everyone’s responsibility. Better patient safety relies on the ongoing commitment from patients, families, carers and all staff to work collaboratively through trust, openness and mutual accountability.”

Perhaps it is time we looked at professionalism lapses as critical incidents, and held all actors appropriately responsible for poor outcomes.

Otherwise, clinicians are simply the scapegoats of a broken system and eventually, it will become too personally distressing and dangerous for them to continue to work in public settings. What a waste.

Associate Professor Louise Stone is a working GP who researches the social foundations of medicine in the ANU Medical School. She tweets @GPswampwarrior.