Helping women to make informed decisions before they become pregnant is the key to minimising risks

Helping women to make informed decisions before they become pregnant is the key to minimising risks

The Centers for Disease Control define pre-pregnancy care as: “Interventions that aim to identify and modify biomedical, behavioural, and social risks to a woman’s health or pregnancy outcome through prevention and management, emphasising those factors which must be acted on before conception or early in pregnancy to have maximal impact.”

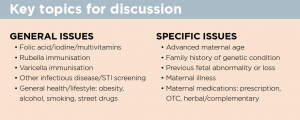

Put simply, pre-conception counselling allows every woman planning a pregnancy the chance to receive information around the potential risks, and to enable her to make informed decisions about the pregnancy.1 GPs are uniquely placed to address many of these risks opportunistically when women of child-bearing age present for any reason at their practice.

It’s important to keep in mind that in Australia around 50% of pregnancies are unplanned. Therefore, it’s often too late for women to attempt significant modifications to their health or lifestyle before the news of a positive pregnancy test.

Smoking, drug or alcohol abuse, poorly controlled diabetes, obesity and exposure to teratogenic medications during the first trimester usually mean that it’s too late for interventions at that stage to be effective in preventing potential adverse consequences.2

Smoking, alcohol and street drugs

For couples planning a pregnancy, general lifestyle issues are the first issues to address. Quitting smoking, alcohol and street drugs should be discussed, along with the plan to access support services, if required. Nicotine replacement therapy, excluding patches, is indicated for use during pregnancy, if needed, and is preferable to continuing smoking. Nicotine replacement can be used in pregnancy as lozenges, tablets, inhalers or gum, while nicotine patches are not indicated for use in pregnancy.

Women who use other drugs, including cannabis, should be referred to a drug and alcohol counsellor to discuss a management plan with an aim to ceasing all recreational drugs prior to pregnancy.

Although we have no strong evidence that the father’s smoking or moderate alcohol intake can affect either fertility or embryofetal development, it is much easier for a woman to implement changes if her partner supports her and joins her in ongoing efforts for a healthier lifestyle.

Nutrition: folate and iodine

Ideally the best way to meet the nutritional requirements of both mother and baby is to eat a wide variety of nutritious foods, but the reality is that many women have a suboptimal diet. The reasons include lack of education, food intolerance and financial constraints; therefore a specifically formulated pregnancy multivitamin supplement offers a chance to ensure that a woman has the appropriate nutrients for a healthy pregnancy.

Current recommendations are that all women planning a pregnancy should take at least 0.4mg folic acid (folate) starting at least one month prior to conception. The main reason is to reduce the risk of neural tube defects (NTD) such as spina bifida.1 Women with unplanned pregnancies miss the boat and only start taking folate once their pregnancy is confirmed at around six weeks, by which time the neural tube has already completed its development.

Since 2007, Australia has had mandatory folate food fortification, but some women at a higher risk of having a baby with a NTD will require higher doses of folic acid fortification (5mg daily). The risk factors for NTD include family or personal history of NTD-affected pregnancy, obesity, diabetes and certain medications, including anti-epileptic drugs.

Studies suggest that folic acid, possibly combined with multivitamins, may also reduce the risk of other birth defects besides NTD, including cleft lip/palate, and limb, renal tract and heart defects.

Iodine is an essential nutrient required to produce thyroid hormones, which are vital for normal development of the brain and nervous system before and after birth. Worldwide, iodine deficiency is the commonest preventable cause of intellectual disability.

The NHMRC recommends that all women who are planning pregnancy, pregnant or breastfeeding take an iodine supplement of 150 micrograms daily. Advice for women with pre-existing thyroid conditions will need to be individualised.

Body weight

Over 30% of women of childbearing age in Australia are overweight or obese, with higher rates in indigenous women3. Maternal obesity is associated with an increased incidence of infertility and many adverse pregnancy outcomes including hypertension, gestational diabetes, thromboembolic events and Caesarean and instrumental delivery. Fetal and neonatal complications include perinatal mortality (stillbirth and neonatal death), birth defects such as NTD and cardiac defects, and babies who are large for gestational age. Neonatal morbidities include hypoglycaemia, jaundice, respiratory distress and the need for neonatal intensive care.

Although the recommendation for overweight and obese women is to try to lose weight prior to trying to conceive by adopting exercise, behavioural modification and diet, the reality is that these measures yield modest results at best, and weight is commonly regained quickly. Bariatric surgery has been increasingly advocated for morbidly obese women wishing to conceive because it’s more likely to result in sustained weight loss than other methods.

Women with abnormal blood sugar levels at the time of conception are at increased risk of having a baby with major cardiac and musculoskeletal birth defects, as are women who are overweight or are otherwise at high risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (past pregnancy with gestational diabetes, family history of type 2 diabetes), and may benefit from pre-conception screening to ensure they have optimal glycaemic control at the time of conception.

Medications

Trends in Australia and other developed countries reflect an increase in the average age of first-time mothers. Apart from being at increased risk of miscarriage and chromosomal disorders (e.g. Down syndrome), older mothers are more likely to have underlying medical conditions which require medication. Older mothers are also more likely to develop medical complications such as hypertension and diabetes during pregnancy.

Unfortunately, many pregnant women are incorrectly advised to stop medications, leaving women at risk of potentially detrimental effects on their own health and that of their baby. For women on regular medication, the risks and benefits of various treatment options during pregnancy must be weighed up. The aim is to consider the safest options that will minimise potential effects on the baby, while ensuring the optimal management of the mother’s condition. This is best done during a pre-conception discussion, with advice from a specialist if necessary.

Women and healthcare providers can also call Obstetric Drug Information services, located in most states, to obtain current evidence-based information and counselling about the safety of medications and other exposures during pregnancy and breastfeeding.4

Infectious diseases

Pregnancy planning should involve screening for sexually transmitted infections, including hepatitis B and C, HIV, syphilis and chlamydia, so that appropriate treatment can be initiated before conception.

Women should be counselled before conception about appropriate precautions to minimise infection risks, in particular meticulous handwashing to avoid CMV and avoidance of undercooked meat and handling cat litter, which increase the risk of toxoplasmosis.

Women with recent acute CMV infection should be advised to avoid pregnancy for at least six months to minimise the risk of congenital infection. Even though there is no vaccine available to prevent CMV, there is an argument for screening prior to pregnancy in order to obtain baseline results in case of possible exposure during pregnancy.

This is particularly relevant for women working in professions at high risk of exposure, such as day care workers, preschool teachers and nurses.

During pregnancy, routine screening for CMV, parvovirus and toxoplasmosis is not recommended because results can be difficult to interpret and lead to unnecessary anxiety. It is important to note that many women may be immune to CMV, toxoplasmosis and parvovirus in the absence of documented past illness.

Vaccinations

A comprehensive pre-conception health check should assess the need for vaccination, particularly for hepatitis B, measles, mumps, rubella and varicella. When history of vaccination or infection is uncertain, appropriate serological testing should be carried out to ensure immunity to measles, mumps, rubella and hepatitis B. However, serological testing for varicella does not provide a reliable measure of vaccine-induced immunity, although it

can indicate whether previous natural infection has occurred.

Rubella and varicella are both vaccine-preventable viral diseases that can cause significant morbidity to the woman and her fetus. Women should wait one month after vaccination with live attenuated virus vaccines before trying to conceive. However, there is no evidence that inadvertent exposure to either of these live attenuated vaccines, even in early pregnancy, poses a significant risk, and this should not be considered an indication to terminate an otherwise wanted pregnancy.

Influenza vaccine is recommended for women planning pregnancy and likely to be pregnant during the winter months. As it is an inactivated vaccine, it can also be given to women at any stage of pregnancy, including the first trimester.

Current recommendations are for a single-dose pertussis vaccination between 28 and 32 weeks of pregnancy, as pertussis vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy has been shown to be more effective in reducing the risk of infant pertussis than maternal vaccination after delivery. Women may be given this vaccination in each subsequent pregnancy (if more than 12 months has passed since previous pertussis vaccination).5

Family history and genetic screening

A brief discussion about family history – both maternal and paternal – is a vital part of a pre-pregnancy consultation. Information about ethnic background is relevant in terms of screening for certain conditions such as thalassaemia because of the higher carrier frequency in certain population groups.

Women of Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, East Indian and South-East Asian descent should be screened initially by FBC (MCV) and HbEPG, and their partner screened if they are found to be thalassaemia carriers.

If both partners are found to be carriers, they should be referred for genetic counselling to discuss the implications, risks and options. Molecular testing can enable the couple to pursue prenatal diagnosis or to consider achieving a pregnancy via IVF and performing pre-implantation genetic diagnosis with the aim of ensuring only unaffected embryos are transferred into the uterus.

Couples with a family history of a specific genetic disorder should be referred for genetic counselling prior to pregnancy so they are aware of their risks and reproductive options. Couples cannot be offered specific prenatal diagnostic testing or the option of IVF and pre-implantation diagnosis without a molecular genetic diagnosis.

To date, carrier screening for autosomal or X-linked conditions has been offered to individuals or couples considered to be at high risk due to either family history or ethnic background. Parents of Ashkenazi Jewish background are at increased risk of being carriers of autosomal recessive conditions including Tay-Sachs disease. Successful community genetic carrier screening programs have significantly reduced the burden of these conditions in the targeted populations: Ashkenazi Jews for Tay-Sachs disease and Greek Cypriots for thalassaemia.

Currently in Australia, most molecular (DNA) tests are not Medicare rebatable so consumers need to consider the costs of pursuing genetic carrier testing. Despite this, many professional bodies including the Human Genetics Society of Australasia, recommend “making couples aware of the availability of cystic fibrosis screening”.

This raises issues about a lack of equity of access to such testing, especially when consumers are potentially saving the public purse a vast amount of money by trying to avoid the birth of a child who could become a long-term recipient of expensive public health services.

Increasing availability and decreasing costs of next-generation genetic sequencing technologies mean that couples may consider a broader genetic carrier screening approach for a panel of autosomal and X-linked recessive conditions.

Several companies have screening panels whereby consumers can order testing online, provide a saliva sample and obtain a result in around four to six weeks at a cost of around $700 to $1000 per individual. Genetic counselling remains important in helping these couples understand potential risks and their reproductive options.

Dr Debra Kennedy is Director, MotherSafe, and Royal Hospital for Women and Conjoint Lecturer School of Women’s and Children’s Health, University of NSW

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care. A report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. MMWR Recomm rep 2006; 55:1-23

- Dickinson JE. Editorial: Preconception assessment: An opportunity often lost. ANZJOG 2014; 54:501-502

- Overweight and obesity in Australian mothers: epidemic or endemic? McIntyre HD, Gibbons KS, Vicki J Flenady VJ and Callaway LK . Med J Aust 2012; 196 (3): 184-188

- https://www.tga.gov.au/obstetric-drug-information-services

- Australian Immunisation Handbook 10th Edition April 2016 http://www.immunise.health.gov.au/nternet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/7B28E87511E08905CA257D4D001DB1F8/$File/Aus-Imm-Handbook.pdf

- http://www.genetics.edu.au/Publications-and-Resources/Genetics-Fact-Sheets