Unless you're blessed with infinite patience, you've probably lost your temper at work. Here's how to keep a lid on it

The hospital is a stressful workplace which constantly tests our temperament. Although some doctors seem to possess endless patience, it is fair (and honest) to say that many have, at some point, been unpleasant to deal with at work.

This could include:

- a rude reply to the ward nurse who has paged you again with something seemingly trivial, or

- a passive-aggressive remark to the emergency doctor with a lacklustre admission request, or

- a belittling comment to the intern who is ill-prepared for the consult or scan they are requesting, or

- a full-blooded reprimand to the night JMO who has mismanaged your patient

Indeed, these scenarios sound all too familiar in the hospital setting, even to the point where they have become institutionalised and an expected occurrence. However, it is important to note that these behaviours may constitute workplace bullying and harassment. To varying degrees, they have all resulted from a loss of temper.

The 2009 Australian Medical Association position statement (revised in 2015) offers the following definitions for workplace bullying and harassment (1):

- Bullying is unreasonable and inappropriate behaviour that creates a risk to health and safety. It is behaviour that is repeated over time or occurs as part of a pattern of behaviour. Such behaviour intimidates, offends, degrades, insults or humiliates. It can include psychological, social, and physical bullying.

- Harassment is unwanted, unwelcome or uninvited behaviour that makes a person feel humiliated, intimidated or offended. Harassment can include racial hatred and vilification, be related to a disability, or the victimisation of a person who has made a complaint.

Consistently, studies have demonstrated that at least 50% of medical trainees have experienced bullying or harassment (2). It can be subtle, insidious and silently endured by its victims. The consequences of workplace bullying and harassment cannot be overstated and include doctor burnout, anxiety, and depression. Furthermore, mistreatment can create cynicism and reduce empathy, which may directly affect patient care (3).

Indeed, not every instance of losing one’s temper equates to workplace bullying and the problem of bullying encompasses far more than doctors losing their tempers. Even so, we would all agree the hospital would be a more pleasant place to work if these instances were minimised.

Why do doctors lose it?

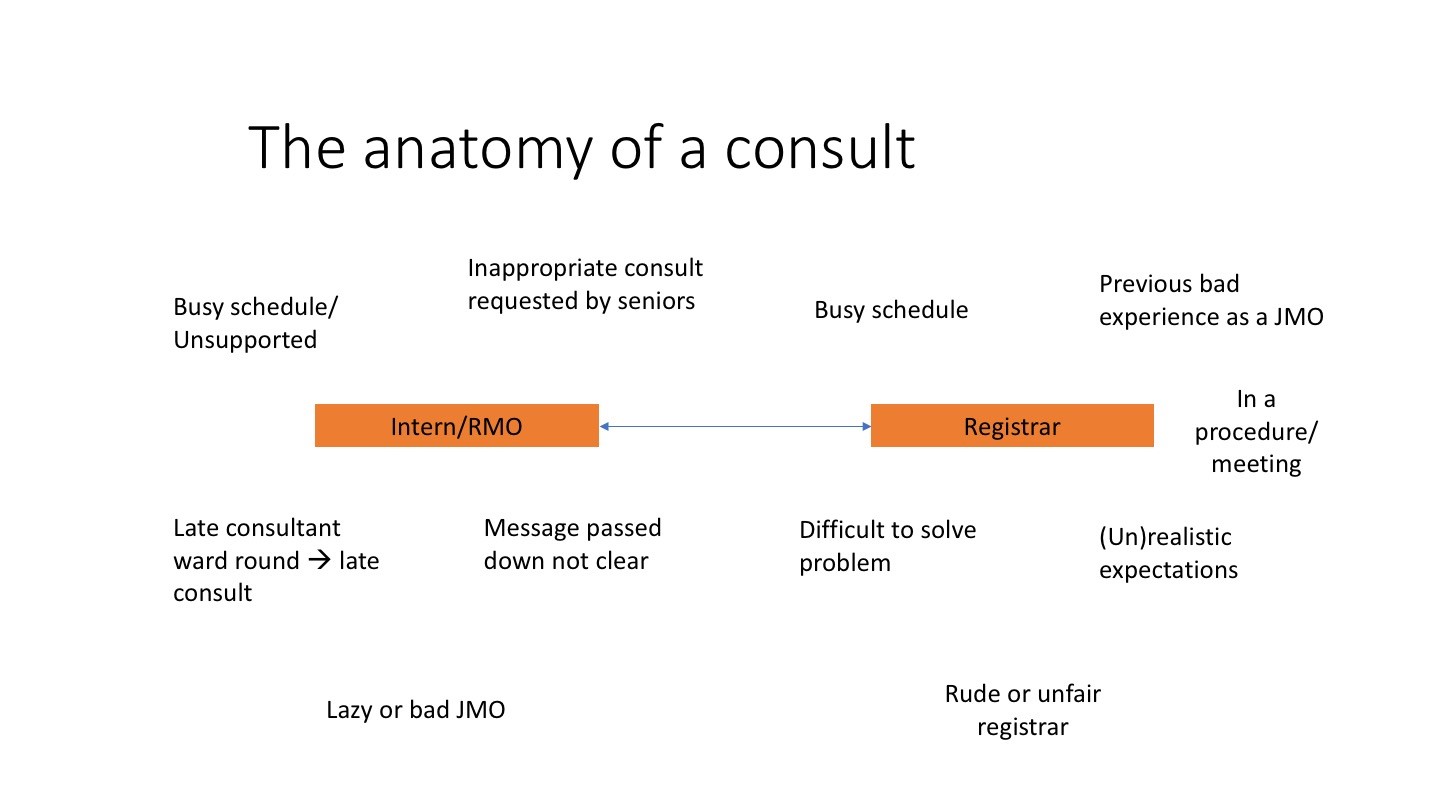

There are multiple reasons beyond the individual person which cause him/her to lose their temper at work. If we look at the example of a JMO requesting a consult from a registrar (a common cause of confrontation at hospital):

Everyone’s temperament is different. If you’re a doctor who can control your temper in the face of stress, then this article is perhaps less applicable to you. I admire and commend you and encourage you to keep doing this! However, if you are like me, where on occasion (or perhaps regularly) work gets the better of your patience, here are a few tips I found useful to help keep my temper in check at work.

Ways to control your temper at work

Reframe your thinking (easier said than done):

- Remember everyone is working for the good of the patient

It can be useful to remind yourself that you and the other staff are all batting for the same team. First and foremost, you are both working together (either directly or indirectly) to improve the outcomes of patients. No one’s primary purpose is to make life harder for you. Everyone plays a different but equal role at hospital. Remember, the person who has frustrated you probably has not had the same training as you so it is not fair to hold them to the same standards of knowledge or “common sense” you possess. Furthermore, they may be following instructions from their superiors (registrar, consultant, nurse unit manager, etc.). Of course this does not mean that you should bring suppressed work-related tension home and transfer it onto your friends and family instead of your workmates. The aim is not to alter whom you offload your stress on, but to avoid reacting to stress in a deleterious way in the first place.

- Remind yourself: there is nothing to be gained by losing your temper

Even if a particular situation is borne out of another person’s deficits and/or deserving of reprimand, there is nothing to be gained by losing your temper. Blowing off steam can offer momentary relief from your frustrations, however, an outburst cannot be unsaid and any hurt it created can be difficult to mend. Instead, there is much to lose including the respect of your co-workers, your reputation, and even job opportunities. There is never a reason to yell at someone at work. Any feedback should be given calmly, objectively, constructively and preferably in a private setting.

Some doctors rationalise their hardened demeanour as a method of teaching those who have (in their opinion) delivered substandard work. In fact, this so-called “teaching by humiliation” has been shown in several studies to be ineffective for most people. A recent pilot study of 150 final-year Australian medical students found less than half of students considered “teaching by humiliation” was useful for learning4. A larger study of 16 medical schools conducted in the United States, reported belittlement by seniors was associated with poor mental health and low career satisfaction5. Clearly, the intention to “teach” is not an excuse for such behaviour.

(For some tips on effective teaching, visit: http://www.meddent.uwa.edu.au/teaching/on-the-run/tips)

- Place yourself in their shoes

Most doctors will recall a time when they have been on the receiving end of someone’s temper. Before you pass on the same treatment to someone else, it can be helpful to remember how it felt when you were in that position. It is likely you would not have wished to be treated that way if given the choice. Although you may have since tolerated the event as part of the experience of working in a hospital, it does not mean it is acceptable to be passed on. Indeed, we should treat others how we ourselves would like to be treated.

Of course, it is difficult to control one’s thought processes before a loss of temper occurs. I have found the above takes a constant commitment to improve, practice and time. Over this time, you will hopefully begin to see improvements in your patience and reactions in various situations.

Practical tips

Thankfully there are some practical measures which can also help while you work on the above:

- Let people know during moments when you are busy or stressed

By informing those around you that you are busy, they will hopefully be more understanding of your situation and be more selective in the things they ask of you. For example, they may limit the conversation to things that are most pressing and return to find you at another time for less urgent matters. Some kind co-workers may even try to help alleviate your busyness. Be wary of other triggers such as hunger and fatigue.

- Phone calls

- Try to avoid taking phone calls or consults during busy times – If a message/request is not urgent, ask to call them back at a future less stressful time when your patience is less stretched.

- Speak to others in person rather than over the phone if convenient – It is much harder to lose your temper at someone face to face than over the phone. If you are frustrated by the person calling you and they are close by, go talk to them in person.

- Allow the other person to speak – Use these first few seconds of the phone conversation to calm yourself before responding. (Close your eyes, take a deep breath, or whatever works for you). This way you are also not interrupting them at the first opportunity.

- Try to keep your workload under control

Look for strategies to keep your workload manageable. Are there any tasks that can be streamlined, redistributed or delegated? It may be tempting to arrive at work early or stay late for the extra (uninterrupted) time to prepare upcoming discharge summaries, assess the new admissions overnight, see leftover consults, etc. However, this is not always the best strategy as it can upset your work-life balance which can also influence stress levels (see below).

- Have a life outside of work / socialise with your workmates

Having regular hobbies, activities and downtime away from work is essential to keep stress levels under control. Avoid spending all your spare time on taking extra overtime shifts, exam study, doing research, attending courses etc. but rather reserve some time for non-medical activities. Secondly, it is harder to lose your temper at people you have shared a drink or meal with. Aim to attend social events with your co-workers (such as after work drinks) and get to know them better as people, not as their hospital roles.

- Reflection

On more than one occasion, my wife has said to me “you could have been nicer to that person” after overhearing my phone conversation with someone from the hospital – a conversation I would otherwise not have thought twice about. This has taught me that what you think is fair may be considered offensive to another person. Therefore, it is important to regularly reflect on your behaviour at work. Also seek and listen to feedback from others to fine-tune your own moral yardstick. If those around you are commenting on your unpleasant manner, then it is probably something you should be working on. Avenues to seek counsel may include a trusted peer, mentor/supervisor, or the confidential employee assistance counselling program (EAP) available at all hospitals.

- Apologise

It is likely that despite your efforts with the above, there will still be moments where you fail to control temper. Hopefully these moments will become increasingly further apart. It is important to apologise during these times. By apologising, you are not only saying sorry to the individual for offending them. You are also acknowledging that losing your temper at work is not acceptable and helping to build a culture in hospital which does not tolerate such behaviour.

Some final thoughts

From my own journey and struggle with controlling my temper at work, I can say that it is not a one-off or overnight change but an ongoing process even after years of conscious effort. However, it is something that everyone has the capability to improve on. Why is it that we can manage to avoid losing our tempers to our superiors at work? As doctors we strive to treat our patients and their families with respect and dignity. At the very least we owe this same respect and dignity to the people we work alongside.

References

- Australian Medical Association. AMA position statement on workplace bullying and harassment. 2009.

- Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, et al. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2014;89:817-27.

- Ivory K, Scott K. Let’s stop the bullying of trainee doctors – for patients’ sake.

- Scott KM, Caldwell PH, Barnes EH, Barrett J. “Teaching by humiliation” and mistreatment of medical students in clinical rotations: a pilot study. Med J Aust. 2015;203:185e1-6.

- Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, Bickel J, Nora LM. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006;333:682-4

This blog was originally published at onthewards.org.

Dr Ken Liu is a Visiting Liver Fellow at Institute of Digestive Disease, Prince of Wales Hospital, Chinese University of Hong Kong.