Better use of testing can put us on the path to outcomes-based healthcare.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, life expectancy dropped in the period 2020-2022 for the first time since the 1990s.

For the first time, children born today may be the first generation with lower life expectancy than their parents.

If you’re one of the seven million Australians living outside of a metropolitan area, it’s even worse. The National Rural Health Alliance says life expectancy for people in remote Australia is up to three years below those in urban areas.

While the statistics are complicated by the covid pandemic, the underlying pattern shows a decade of increasing life expectancy that is now in decline.

Australia has one of the world’s best healthcare systems, partly due to the 1984 introduction of Medicare. However, growing GP waiting lists, ambulance ramping, and public hospital crowding are obvious signs this system is not entirely healthy.

Pressure grows when we combine our aging population and increasing incidence of chronic disease with predictions of a lower taxation base, as outlined in the Commonwealth Treasurer’s Intergenerational Report 2023, investments in healthcare will be increasingly difficult to fund.

Australia’s healthcare system is heavily activity-based. That is, providers get paid for “doing something”. Effectively the system is incentivised on the number of services and not necessarily the patient outcome. We know there is a shortage of services and health professionals across many areas in Australia, particularly in regional areas where the need for better healthcare is greatest. But building new hospitals and training new healthcare professionals is expensive and takes time – a decade or more.

What if there was a more sustainable approach to delivering healthcare that focused on outcomes rather than activity?

There are examples of comparable economies that have started their journey to outcomes-based healthcare. The innovative diagnostic tests, technology and digital health enablers are now available to commence this transition. Genomic tests, including gene sequency, proteomic and biomarker tests, sophisticated point-of-care tests and clinical decision support software are transforming the way healthcare is delivered in other parts of the world.

In Australia, regrettably, we are relatively slow to adopt these technologies.

In the UK for example, medically important genomic tests are identified and made available through the NHS in less than 18 months. In Australia, it can take eight years or more to have such tests funded through Medicare.

That’s not to criticise the Australian process for evaluating these innovative new tests. It’s not easy to fully quantify the economic value of tests to be funded by taxpayer dollars. But when you understand that over 70% of all medical diagnosis and treatment decisions depend on a pathology test – and for cancers it’s 100% – the cost of testing is trivial in the overall scheme of healthcare expenditure.

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare $3.6 billion was spent on non-hospital pathology services in 2020-21; approximately $223 billion (excluding pathology services) was spent on health goods and services. And while Australia’s health cost statistics are far from transparent, it is likely that less than 2% of the healthcare budget is spent on guiding 70% to 100% of all medical diagnostic and treatment decisions.

Strategic investment in testing that moves Australia towards a wellness-based system should now be earnestly considered. Failure to change consigns us to a progressively more unsustainable, inaccessible and expensive healthcare system.

A good example comes from a recent health economic study that examined the costs and benefits of investing (or failure to invest) in simple blood tests for conditions such as chronic heart failure and pre-eclampsia (dangerous high blood pressure in pregnancy). This study demonstrated that our healthcare system has foregone $7 billion in value, lost for the sake of funding a small number of relatively inexpensive tests. And this ignores the personal and human cost.

Failure to change is also likely to see Australia decline in status as a healthcare nation. Most of our near neighbours and southeast Asia have already adopted tests to identify genomic variants, inherited disorders and some cancers in circulating blood (sometimes called cell free DNA or cfDNA). This is particularly applicable to people who are being monitored for a recurrence of their cancer. Australia’s adoption of this technology ensures we lag significantly behind our near neighbours, as it does for a range of genomic, point of care and other biomarker tests.

Yet it is these very tests and technologies that could lead Australia into a wellness-based health environment. Genomic tests can be used to predict healthcare status so that early treatment or intervention can be accessed. Especially in cancer diagnosis and treatment – genomic sequencing can identify in exquisite detail, the type of cancer and, increasingly, the specific treatment that will be effective.

A good example is CAR-T therapy for cancers, where genomic and proteomic tests inform the specific configuration required for the patient’s own T-Cells (immune system) to seek out and kill cancer cells.

Pharmacogenomic tests can identify which treatments will work so that a patient gets the right one first time. These tests can also identify drug resistant infections to better target treatment. And even identify an individual’s lifetime risk of having a heart attack.

Imagine knowing well in advance if you are at high risk of a heart attack during your lifetime. What choices would you make in your lifestyle to minimise the downside?

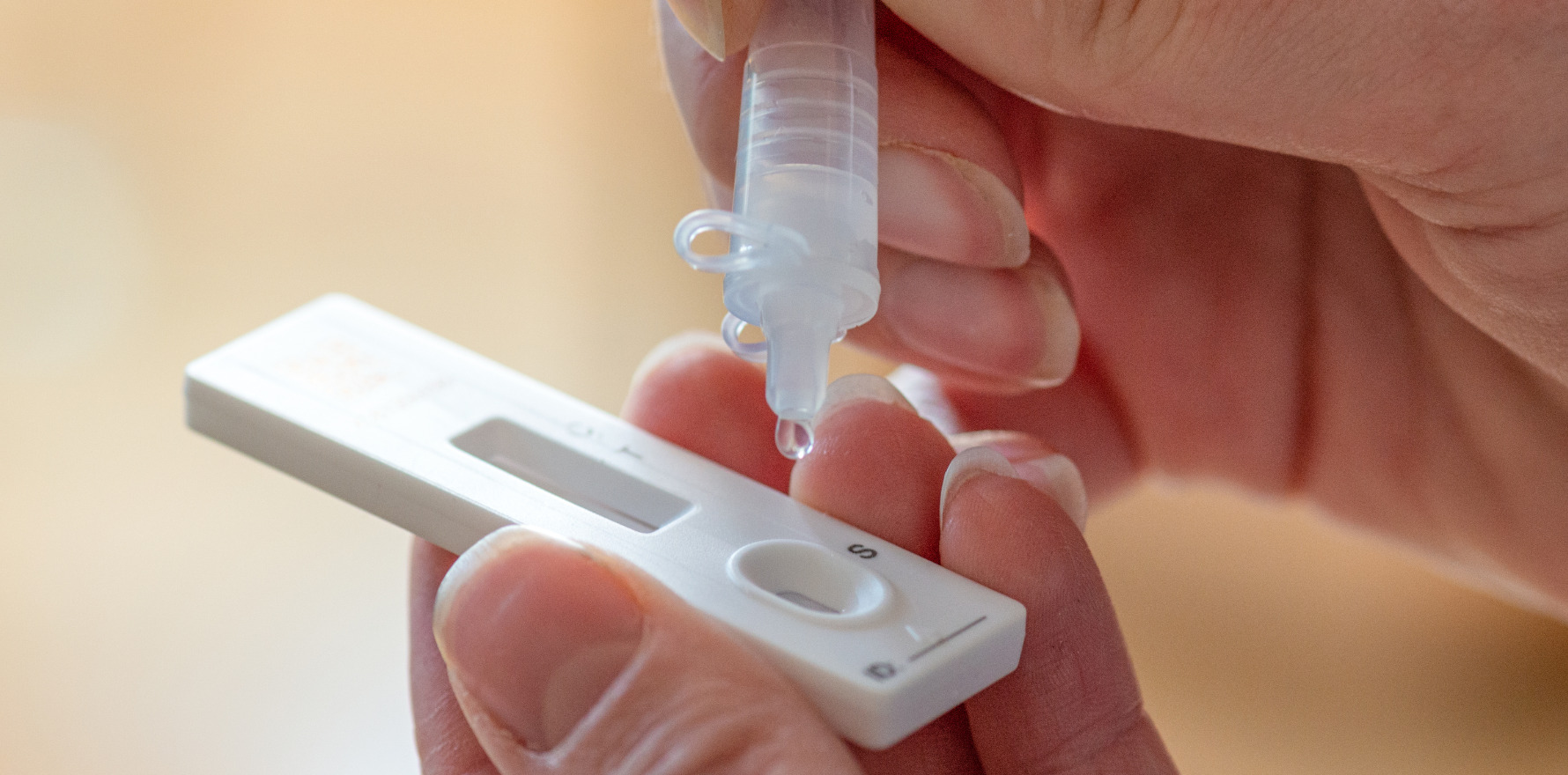

Point-of-care tests bring the laboratory to the patient, facilitating faster diagnosis and treatment. Australian-based studies, performed over the past 20 years by the Kirby Institute and a team at Flinders University in South Australia, have demonstrated the benefits of point-of-care testing in hard-to-reach populations.

Evolving our healthcare system is not easy or quick, but we do need to make a start. The good news is that we have a lot of what we need at our fingertips. And while an investment is required, the return will be a sustainable, wellness-based economy and a healthy population. We just need to willingness to embrace change.

Dean Whiting is a qualified clinical biochemist and CEO of Pathology Technology Australia.