Is ‘partially effective’ and ‘not based on robust methodology’ good enough for the DoH compliance program when it causes widespread fear and anxiety throughout the GP community?

Is ‘partially effective’ and ‘not based on robust methodology’ good enough for the DoH compliance program when it causes widespread fear and anxiety throughout the GP community?

The Australian government has been conducting forms of compliance activities around health provider behaviour since 1953 when the PBS was born and checks were needed around prescribing behaviour.

When Medicare was born in 1973, more compliance activity started, to check benefit claiming.

The current compliance program doctors operate under was established under the Department of Health in 2015. It is meant to protect the integrity of the country’s health benefits system, mainly that the PBS and MBS claims are done within the law.

At the pointy end of today’s compliance regime, the Professional Services Review (PSR), where a doctor can really get into trouble and have their life turned upside down if they are suspected of breaching prescribing or claiming regulations, has operated since 1994. The PSR is controversial because once you find yourself within their grasp, you are almost certainly a marked man/woman.

The PSR has a nearly 100% ‘conviction’ rate, so you’ll usually need to pay back a lot of money, often money you never saw because you are an employee or contractor yet you are sometimes forced to pay back all the money you made for your employer. And you may be publicly humiliated through publication of cases.

If you want to fight, you have very little in the way of procedural fairness in the system as things stand, so you’ll need to lawyer up, at considerable cost. If you lose, you likely will have doubled down on your losses, which is probably why the acceptance of a finding is so high. The system is stacked against you once you’re in it. Here’s an interesting recent case of someone trying on the latter.

The good news is that in relative terms, the numbers that get caught in the PSR web each year are actually minuscule. In the last year it only required 79 doctors out of a potential 88,000 practising across the country to pay back $24.4 million of a total MBS spend of $20.2 billion. So by rights, you probably need to be very unlucky, or very bad, and most GPs should not need give the PSR much thought. Overall there should not be much fear of either the PSR or the DoH’s compliance activities.

But that’s not the case at all, unfortunately.

In the last few years the DoH has ramped up its efforts considerably, most visibly through targeted letters to doctors on a compliance level lower down the ladder from the PSR level, which have become known as nudge letters. Nudge letters are notifications which are polite but target you directly with information that indicates you are in the DoH’s sights for certain prescribing or billing behaviour (identified these days by stats and analytics of payment and prescribing records) which the DoH analytics people have calculated might constitute inappropriate behaviour. They are sent based on you being an outlier according to data analysis of prescribing and claims.

Nudge letters have led to widespread fear and anxiety among GPs. The DoH claims that the letters are effective and that up to 50% of doctors respond immediately to such letters and alter their behaviour. In 2018/19 the DoH estimates that such letters may have saved the system up to $129m in incorrect billing or test ordering.

But it is very likely that the fear being created by the letters is leading to an overcorrection. GPs want a buffer between them and any possibility of being caught in the compliance net so they alter their behaviour. In the case of billing GPs will deprive themselves of income. Income which is already under enormous stress after years of MBS freezes.

Necessarily, the rules around what to bill and when are changing constantly, mostly through reviews to items and introduction or deletion of items, and this compounds the situation. There is plenty of room for interpretation, error, and therefore, targeted letters.

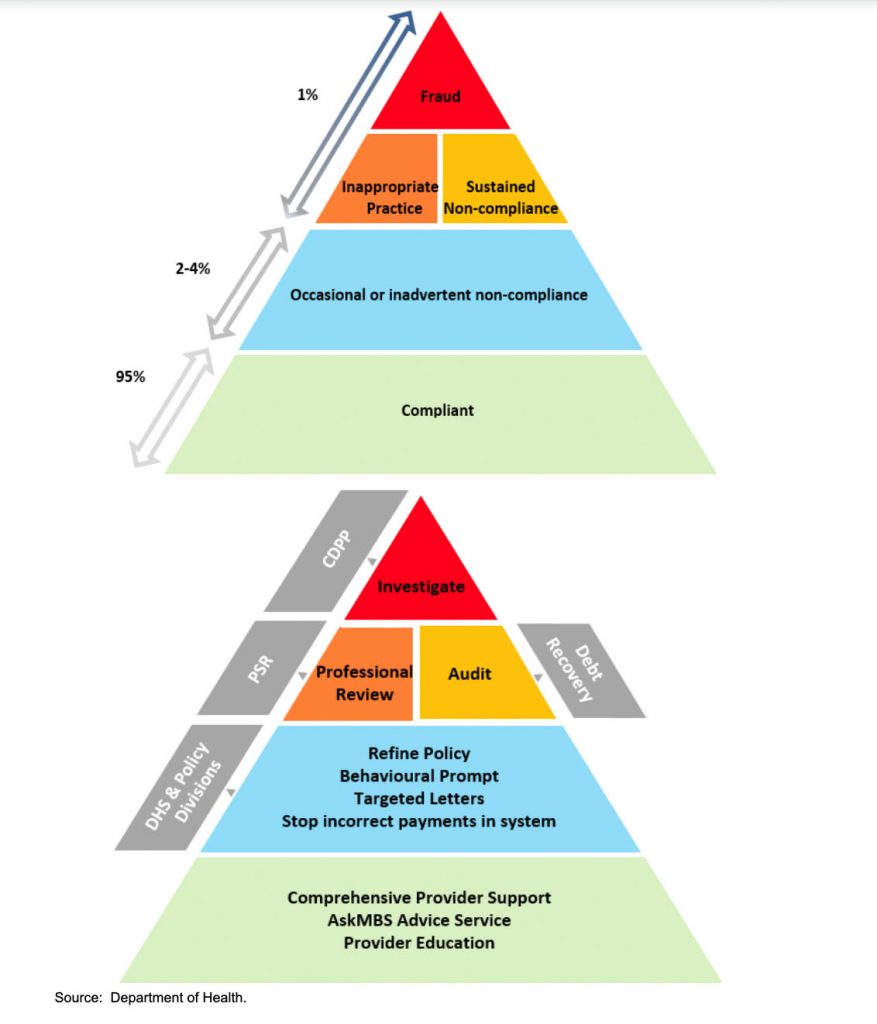

The PSR is near the tip of the DoH compliance iceberg (see figure 1). The tip is fraud, and legal action by the department of public prosecutions. If you’ve climbed the dizzy heights to PSR, audit or fraud you’re a one percenter according to the DoH.

Below this level is a ‘grey’ segment which the DoH suggests makes up only 2-4% of the doctor population. At this level you are occasionally or inadvertently non-compliant. The key element in your management in this segment is ‘nudge letters’.

If you get one of these letters, you still are elite, according to the DoH. The top 2-4% of the pyramid. So 95% of doctors are technically either getting it right when you get it wrong, or they are behaving better. That’s partly nudge tactics. The psychology of shame.

But the DoH estimate of misbehaviour at the nudge letter level of 2-4% isn’t how the stats roll out. In 2018/19 the DoH sent 12,061 targeted letters. Most would have been to GPs. That’s likely to be more than 30%, or about 8,000 GPs who prescribe or claim getting shame/fear letters. If, as the DoH claims, at least 50% respond immediately, and presumably some more are non-compliant but don’t respond, then the DoH is targeting something like 15-20% of GPs, not 2-4%.

If 8,000 or so GPs get a letter in one year, and about 50% of them acknowledge their nudge letter and alter their behaviour (as the DoH says), then that 4,000 will likely disappear off the segment not to come back. In the next year a mostly different 4,000 or so, at least, would be targeted. So within a few years you might have something between 12,000 and 15,000 GPs who’ve seen a nudge letter.

Now you have widespread fear for good reason. A lot of GPs are seeing a nudge letter over just a few years.

If you get one of these letters, you aren’t in trouble yet, but you are among a class of doctors of whom some will graduate to the PSR and audit level. You are now in striking range. Now we are talking about the psychology of fear.

The DoH is having a much greater impact than the 2-4% it suggests it has on its pyramid. If you add media or just social media amplification of a GP’s story of unfair targeting, then you can easily see why nudge letter strategy has become so controversial in the profession. It’s reaching nearly everyone in some way. It’s hard not to believe that this is strategy on the part of the DoH.

“My initial shock and outrage has settled, but the letter certainly caused some angst, as it has no doubt done with the thousands of other GPs who will have received a similar letter. I know the MDOs have had a number of calls from upset members who feel they have been unfairly, and even incorrectly, targeted for what appears to be poor practice” – One of 5,000 GPs who received a letter about their opioid prescribing levels in 2018.

Given the mental impact of such a strategy on the profession you’d of course expect that the DoH would have very clear evidence to support the validity of such a strategy.

But according to an Australian National Audit Office review released a few weeks ago, it actually doesn’t.

As a high level summary, the report released last month stated that the DoH’s approach to health provider compliance was only “partially effective”, its reporting “was not based on a robust methodology”, and “there was limited evidence that compliance outcomes were systematically monitored and assessed”.

There should be some irony in the auditor general of doctors getting an audit assessment like this. But the DoH didn’t seem to blush. It accepted the findings as if they were a few blips that needed adjusting and promised to fix up the identified issues.

Reading the DoH acceptance summary, you get a feeling that the nudge letter campaigns aren’t about to subside.

“The Department of Health welcomes the findings in this report and accepts the recommendations directed to the department. The department is committed to effective implementation of the ANAO recommendations and has already taken steps to address the issues in this audit,” starts the DoH response.

Nothing to see here, everyone can move on then?

In the report the ANAO asks three seminal questions of the DoH’s compliance efforts:

- Does Health identify potential non-compliance appropriately and use an effective approach to prioritise projects? No.

- Are Health’s actions to treat non-compliance proportionate? Yes, but see question 1.

- Does Health monitor whether the expected outcomes of the compliance programs are being achieved? No.

I’ve put the answers in here as a translation of what the ANAO actually concludes for each question itself. The ANAO is wordy and fluffy, but inescapably they aren’t happy with how the DoH picks its targets and measures its success for future targeting.

The most important conclusion is that the ANAO doesn’t think that the DoH identifies non-compliance appropriately. If this is true, then does the DoH have a case for continuing nudge tactics and traumatising our GP population more than Medicare freezes, COVID-19 and ePIP forms have?

There is a classic government induced twist to this story because the ANAO isn’t actually concerned with who the DoH is targeting, how or what the effect of that targeting is, beyond saving more money. They aren’t concerned that nudge letters are potentially adding a level of stress to one of our most important community based professions, and that this might be affecting productivity of the profession badly, with all the downstream effects on community that this might create.

It is concerned that the nudge letters, and some of the other strategies being used, aren’t necessarily the best bang for buck for the DoH, and if they aren’t, they are wasting government money.

This is sometimes how the ANAO works. In the case of the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA), they gave a clean bill of health largely based on the Agency crossing its ts and dotting its lower case js on all its processes and financials. The fact that the My Health Record (MHR) is a monstrous failure in terms of achieving its objectives, and therefore up to $2billion of taxpayer money may have been wasted, wasn’t on its list of things to check in its audit.

But unlike the ADHA example, the ANAO, in calling the DoH out for not being able to properly identify and prioritise its compliance delivery (based on return on investment), is also identifying a systemic issue in the whole set up. If it can’t properly identify and prioritise its compliance, on what grounds is it sending nudge letters?

The DoH would likely point to 50% of nudge letters being effective because it reports that 50% of recipients respond indicating they will change their behaviour. That is a good percentage, and perhaps nudge is effective in that way.

But what about the other 50% and the damage that might being done in productivity and in trust of government overall? What if nudge alters behaviours in ways that reduce the effectiveness of delivery of certain services because GPs are afraid to go too close to identified areas of controversy? What if the money spent on nudge could be far better spent on something much more targeted and that would return much higher in terms of actual poor behaviour, as the ANAO would like? What if the full return equation for nudge, taking into account all of its effects of very loose targeting, and the effects of shame and fear, is actually negative, for both the DoH and the country?

That’s a very real prospect that the ANAO has identified in its report and why it’s very worrying that this report seems to have been treated so casually by the DoH itself.

The ANAO says the DoH is not targeting properly and therefore wasting money because there has been very little assessment of target risk when they identify projects. In simple terms it isn’t able to say it is targeting the right people and can’t prove return on investment.

In its response to the Audit the DoH points out that it has already implemented changes to address many of these issues, including introducing a ‘risk based’ approach to identifying and prioritising investment in activities.

It doesn’t look like that means dropping nudge letters because they are a very untargeted strategy.

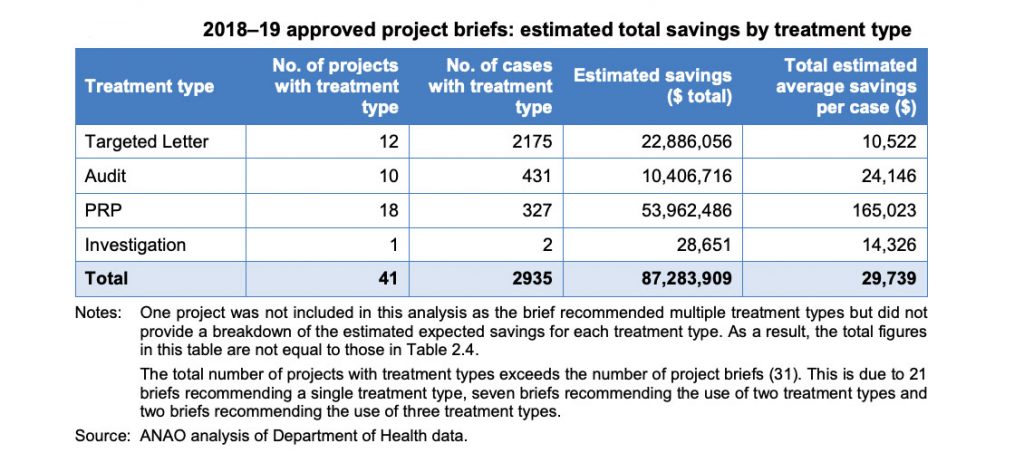

The ANAO report actually suggests that on a savings per case basis, targeted letters are the least effective tactic for the DoH.

But on a cost per case basis, and on an overall savings basis (See chart 2 below), nudge letters are likely to be the most effective strategy, even when the DoH does its risk targeting better.

Turns out, writing scary letters and sending them as far and wide as you can, is pretty cheap. So cheap that in any return on investment strategy it’s highly likely it’s not going to be dropped.

The problem is that the DoH algorithms for risk are only taking into account the variables of cost saving per targeted activity. Of course writing a letter is cheaper.

But it’s a spray and scare tactic to keep the masses guessing and potentially simply doing less in the danger areas for fear of somehow accidentally crossing a line.

No one is analysing what the downside of this might actually be here over time to community care.

Is it a good thing for primary care medicine that the DoH and therefore government is seen first and foremost as a punisher and potential gaoler? The government is technically the employer of GPs. What sort of an employment relationship creates fear and loathing like this?

Yes, compliance and some degree of oversight is a necessary and vital activity in a complex system of medical benefits.

But the last few years of ramp up have taken compliance activity into a world where government is destroying its trust relationship with its most important healthcare employees they have. And very likely denuding the quality of the whole primary care system.

The ANAO report in typical government style isn’t actually auditing for this overall effect on the system.

But it should be.