Children in the outer suburbs of major cities are twice as likely to have asthma due to health inequalities, research suggests.

Children are twice as likely to have asthma if they live in the outer suburbs of major cities compared to children in the inner city, research shows.

Research using Australian census data shows that there is a 12% prevalence of asthma among children aged five to 14 living in the outer suburbs, compared with 6% of children in the inner suburbs.

“Remarkable health inequalities of a similar nature were uncovered in each city, with asthma risk rising by a factor of two from the inner city to the outer suburbs,” the researchers said in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

“Although the impact of outdoor air pollution is centrally concentrated in every city except Brisbane, its contribution to risk is overwhelmed by those of socioeconomic status and climate and environment.”

In 2021, the census included a question about chronic health conditions – including asthma – for the first time.

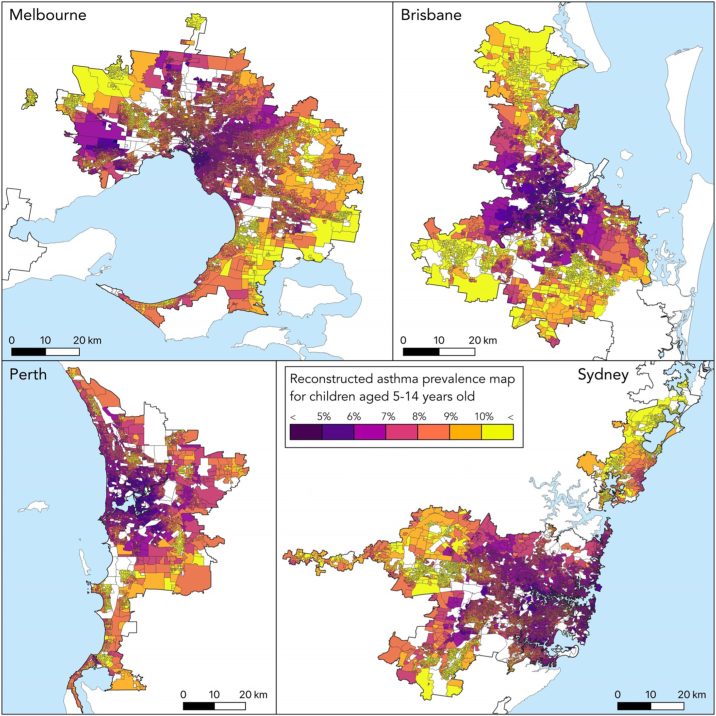

The Telethon Kids Institute and Curtin University researchers used asthma census data of the four largest cities – Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth – along with statistical modelling and satellite imagery to map the distribution of childhood asthma.

They found that the prevalence of asthma in children aged five to 14 years was 7.9% in Sydney, 8.2% in Melbourne, 8.5% in Brisbane and 7.6% in Perth.

“All four cities also display similar scales of spatial variation in asthma risk … of 6% to 12% in Sydney, 6% to 12% in Melbourne, 5% to 13% in Brisbane, and 5% to 11% in Perth.”

The researchers said that Australia was committed to reducing health inequalities and the disease burden of asthma by lowering concentrations of air pollutants such as through installing rangehoods or replacing gas stoves with electric stoves.

However, they said their analysis “confirms the intuition that the health benefits of this intervention will predominantly favour inner city residents”.

“Unless other policies are simultaneously pursued to target asthma reductions in the outer suburbs and lower socioeconomic status areas, the intracity health inequalities shown here can be expected to worsen significantly.”

Lead author and geospatial modelling expert Associate Professor Ewan Cameron said they thought inner cities would have the most childhood asthma because of heavy traffic flow and air pollution.

“Instead, the pattern we see is one of increasing asthma risk towards the outer areas of cities,” said Professor Cameron, from Telethon Kids Institute and Curtin University.

Professor Cameron said that pattern was the same across all four cities.

“In many ways it was surprising just how similar all the cities were,” he said in a statement.

“We found that in every city there was that same trend – increasing prevalence from the wealthier inner-city suburbs to the poorer outer-city suburbs.

“For Perth and Sydney, for example, when you look at the maps you immediately see it’s much lower in the more advantaged inner, northern and beach suburbs compared to suburbs that are more inland.”

Professor Cameron said areas that experienced large daily temperature variations had higher risks of asthma.

“More extreme weather can be a factor in triggering asthma,” he said.

Earlier studies had shown that the risk of developing asthma was strongly shaped by socio-economic factors, he said.

“These factors include higher rates of chronic family stress and poor housing quality, including dampness and poorly ventilated gas stoves, as well as dietary and obesity factors,” said Professor Cameron.

“People in lower socio-economic areas, many of whom are renting, often lack the means to alleviate these issues and may have poorer access to health care support for asthma management.”

The researchers noted that the date of the census may have affected the data.

“The 2021 census was conducted in August, which is a winter month in Australia and is in turn a peak time for ‘exercise-induced asthma’ but not for thunderstorm asthma, for example,” they wrote.

Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2024, online 12 March