CVD prevention and the role of general practice has never been so critical.

Primary care clinicians face a backlog of patients in need of preventative and chronic disease related cardiovascular care.

During a period of competing priorities, particularly with the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out, the prevention of CVD and your role in it has never been so critical.

Wave of chronic diseases on the horizon due to COVID-19

Two years on from the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is becoming clearer that the devastating mortality and morbidity inflicted by the virus may be followed by a wave of chronic diseases in years to come.1 The COVID-19 pandemic saw patients postpone or forgo a wide variety of health services, ranging from emergency treatment of acute conditions to routine check-ups, including the Heart Health Check.2

In fact, at least 27,000 fewer Heart Health Checks were delivered between March 2020 and July 2021 because of the pandemic. These checks could have prevented up to 350 heart attacks, strokes and cardiovascular related deaths over five years.3

A/Prof Ralph Audehm discussing the critical role of general practice in CVD prevention.

Clinical assessment and management of CVD risk is suboptimal

Almost 580,000 adults are living with coronary heart disease, which remains the leading cause of death in Australia.4

Australian Guidelines for the Assessment and Management of Absolute CVD Risk recommend regular cardiovascular screening for adults aged 45 to 74 years without a history of CVD.5 Yet, adherence to the peak CVD prevention guidelines in Australia remains suboptimal.6

Based on recently published data from the first year of the Practice Incentives Program Quality Improvement (PIP QI) Measures, half of eligible Australians do not have all four risk factors recorded to enable absolute CVD risk assessment – tobacco smoking status, diabetes type or HbA1c result or fasting glucose tests, blood pressure and lipid levels.7

Reduced screening in primary care can lead to avoidable cardiovascular events and deaths in high-risk individuals. One-third of patients with no prior CVD presenting to a Queensland hospital with acute coronary syndrome were found to have a high absolute CVD risk score and of these, only one in five were on appropriate guideline-recommended pharmacotherapy.8

Best practice CVD risk assessment and management

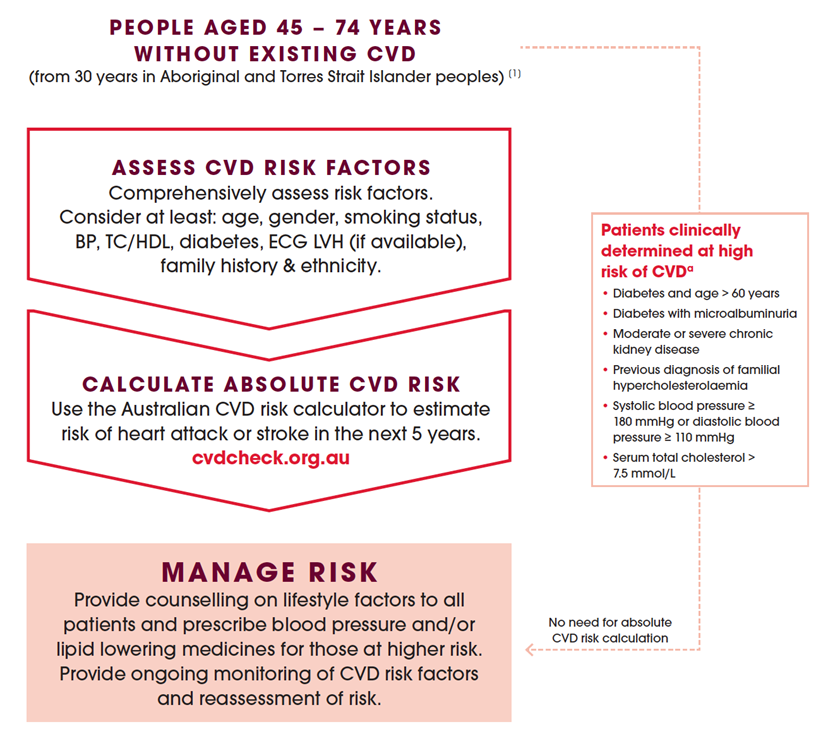

Absolute CVD risk assessment estimates the cumulative risk of multiple, and sometimes synergistic risk factors, to predict a heart attack or stroke event.5 Current Australian guidelines recommend the use of a validated Framingham based risk prediction algorithm to estimate an individual’s risk of a CVD event over a five-year period.

“The thing is we can do something about it. We can intervene in those people at high risk or who have had an event already.”

Ralph Audehm, GP and academic.

Figure 1: The recommended approach to CVD risk assessment and management according to Australian Absolute CVD risk guidelines5

a. Adults with any of these conditions do not require absolute CVD risk assessment using the risk equation because they are already known to be at clinically determined high risk of CVD and should be managed accordingly.

International guidelines are increasingly emphasising the place of risk calculators as a starting point, not as the final arbiter, for decision making in the primary prevention of CVD. Risk enhancing factors, as labelled by the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines on the Primary Prevention of CVD, can help guide decisions about preventative interventions in select individuals.9 Some of these factors are family history, metabolic syndrome, chronic inflammatory conditions, high risk ethnicity and elevated lipid biomarkers such as lipoprotein(a).

The Heart Foundation, on behalf of the Australian Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance, is currently leading an update to the 2012 Absolute CVD Risk Guidelines and risk calculator.

Life-saving CVD risk assessment made easy

In an effort to help GPs, practice nurses and other primary care professionals re-engage with patients about their heart health, the Heart Foundation has developed the Heart Health Check Toolkit.

This digital resource provides a range of tools and easy-to-use templates all in one place to streamline the systematic implementation of Heart Health Checks via a whole-of-practice approach.

CVD risk assessment and management templates are now embedded in popular GP software including Best Practice and MyGPMP tool on Topbar, and are also available in RTF formats.

“Templates were really easy to upload and use by GPs and nurses.”

Jenni Hall, experienced practice nurse.

Anecdotal feedback from general practices across Australia indicate that structured processes to support CVD screening in primary care help to prioritise prevention. Systematic identification and recall of high-risk individuals create the biggest return on investment as it relates to CVD events prevented.

Practice nurse Jenni Hall sharing her experience with the Heart Health Check Toolkit.

Learn more about the Toolkit today

and use it during your next Heart Health Check

The clinical assessment and management of CVD risk is subsidised by the Heart Health Check MBS items 699 and 177 and incentivised through the PIP QI program.

This activity has been funded by the Commonwealth Department of Health, as part of the Public Health and Chronic Disease program.

References

- KE Mansfield, R Mathur, J Tazare, AD Henderson. ‘Indirect acute effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in the UK: a population-based study’, Lancet, 2021, 4(4):e217-e230.

- K Sutherland, J Chessman, J Zhao, G Sara, A Shetty, S Smith, A Went, S Dyson, JF Levesque. ‘Impact of COVID-19 on healthcare activity in NSW, Australia’, Public Health Res Pract, 2020, 30(4):e3042030.

- Heart Foundation internal modelling data. September 2021

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, National Health Survey 2017-18, Data customised using TableBuilder

- National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance, Guidelines for the management of absolute cardiovascular disease risk 2012, NVDPA.

- CM Hespe, A Campain, R Webster, A Patel, L Rychetnik, MF Harris, DP Peiris. ‘Implementing cardiovascular disease preventive care guidelines in general practice: an opportunity missed’, Med J Aust, 2020, 213(7):327-328. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50756. Epub 2020 Sep 2. PMID: 32880959.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2021. Practice Incentives Program Quality Improvement Measures: National report on the first year of data 2020-21. Cat. no. PHC 5. Canberra: AIHW

- Bailey A, Korda R, Agostino J, et alAbsolute cardiovascular disease risk score and pharmacotherapy at the time of admission in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome due to coronary artery disease in a single Australian tertiary centre: a cross-sectional studyBMJ Open 2021;11:e038868. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038868

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2019 Sep 10;140(11):e649-e650] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2020 Jan 28;141(4):e60] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2020 Apr 21;141(16):e774]. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678