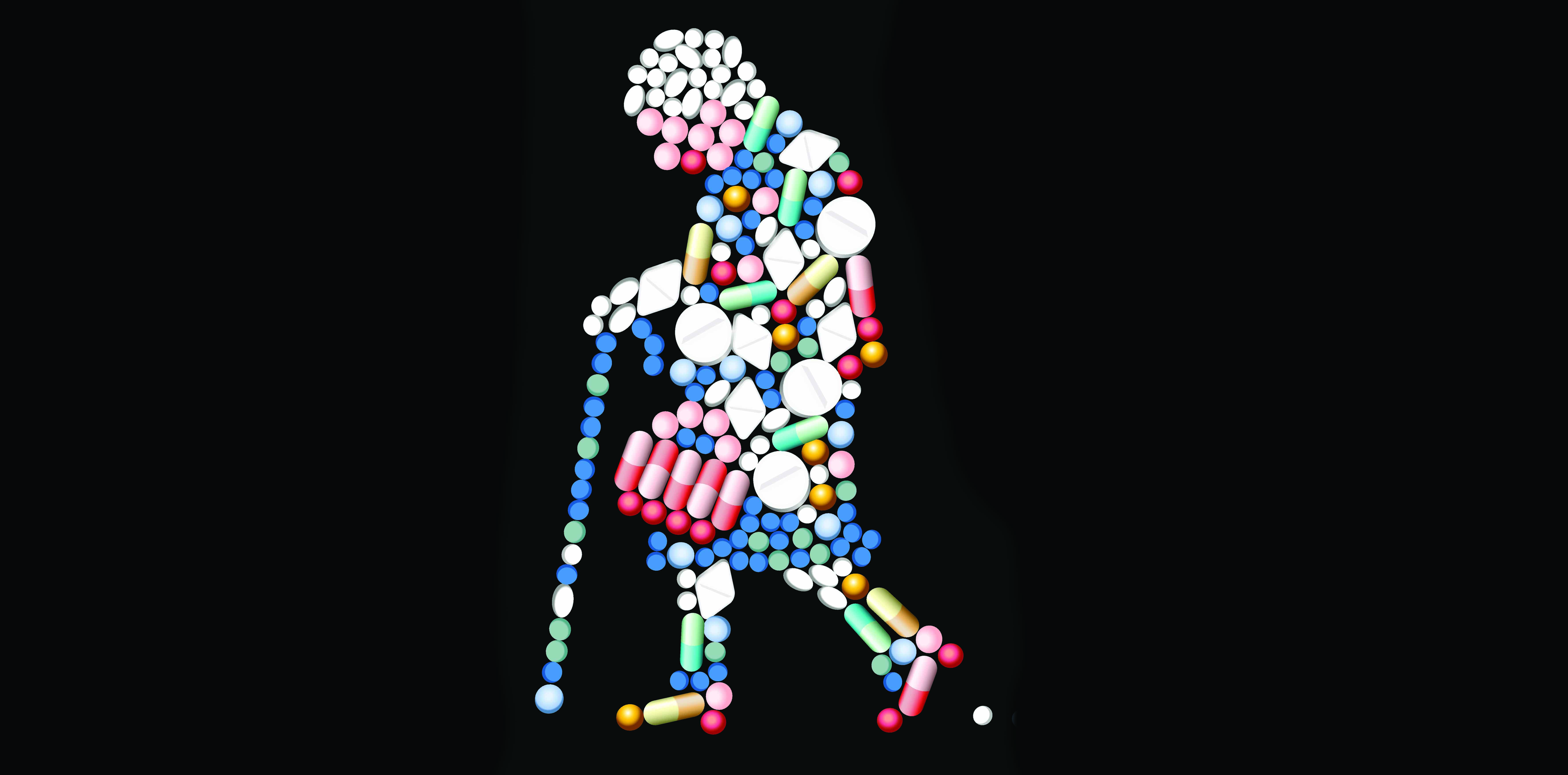

Alternative treatments to anticholinergic drugs should be considered for middle-aged and older people, a new study suggests

Around one in every 10 dementia diagnoses may be related to anticholinergic drugs, a UK study has suggested.

The observational study of around 280,000 people found a 50% increased risk of dementia in people aged over 55 who regularly took anticholinergic medication in the previous 10 years.

Dementia risk was highest for study participants taking anticholinergic antidepressants, bladder antimuscarinics, antipsychotics and antiepileptic drugs.

The study couldn’t establish causality, but it did “highlight the importance of reducing exposure to anticholinergic drugs in middle-aged and older people,” the authors said.

If this association between dementia and anticholinergic drugs was causal, the study would suggest that around 10% of dementia diagnoses could be attributed to anticholinergic drug exposure, the authors said.

“Alternative treatments should be considered where possible, such as other types of antidepressants – for example, SSRIs not including paroxetine,” first author Carol Coupland, a professor of medical statistics in primary care at the University of Nottingham in the UK, told The Medical Republic.

“Regular medication reviews should be carried out to ensure patients aren’t taking these drugs for longer than needed.”

Some highly anticholinergic drugs – for example, benzhexol and benztropine – were listed as “do not prescribe ever” in the American Geriatric Society’s modified Beers criteria, but other anticholinergic drugs weren’t listed, Dementia Australia’s honorary medical adviser Associate Professor Michael Woodward said.

“Certainly, GPs need to exert additional caution, but there is no blanket rule about not prescribing [anticholinergic drugs to older people],” he said.

Anticholinergic drugs are known to cause short-term confusion and memory loss in older people.

“Use of these drugs is generally considered to be relatively contraindicated in any elderly person, particularly those that already have cognitive impairment,” Associate Professor Roger Clarnette, a geriatrician at the University of WA, said.

But this class of drugs is useful for treating a range of health conditions, including urinary incontinence, depression, allergies, respiratory conditions, Parkinson’s disease, eye conditions and psychosis. As a result, up to 60% of older Australians use anticholinergic drugs from time to time.

“A major problem is the use of antipsychotic drugs to manage behavioural issues in those with dementia,” Professor Clarnette said. “These drugs are often intended to be used for a short duration, but deprescribing often does not happen and toxic effects are very common as a result.”

Doctors would have to balance pros and cons of anticholinergic drugs, Professor Julian Hughes, a recently-retired dementia expert at the University of Bristol in the UK, said.

“There are alternatives to most of the anticholinergics mentioned in the paper, but they have their own side-effects, some are less well known, some are more expensive, some are less available.

“In individual cases, therefore, doctors may yet decide to use an anticholinergic. This paper encourages them to think harder about alternatives given the increasing evidence of harm.”

Previous studies have linked anticholinergic drugs and dementia, but the results have been inconsistent.

This latest study was large enough to control for potential confounding variables such as age, sex, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption and comorbidities.

However, it provided “only incremental new knowledge” and randomised deprescribing trials were needed to confirm the result, US experts wrote in the accompanying editorial.

JAMA Internal Medicine 2019, 24 June