This inflammatory skin condition is often misdiagnosed and has a devastating impact on quality of life.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a highly morbid inflammatory skin condition that is significantly under-recognised and complex to treat, with much research being carried out to better define its pathogenesis.

It is characterised by the formation of painful inflamed nodules, abscesses and fistulae in intertriginous sites which undergo perpetual cycles of inflammation, healing and scarring. The estimated prevalence of HS in Australia of 0.67% (CI 0.53 – 0.84), with twice the predilection for females compared to males (Calao et al., 2018).

HS is highly associated with metabolic, cardiovascular and psychological comorbidities, and causes profound impairment in quality of life (Matusiak, 2020; Mortimore et al., 2022). Despite being relatively common, HS is frequently misdiagnosed, with the average duration between first manifestation of symptoms until diagnosis being 7–10 years (Saunte et al., 2015). Diagnostic delay contributes to enormous physical disability and psychological impact upon patients who spend years awaiting appropriate treatment (Kokolakis et al., 2020).

Management is ideally implemented early and coordinated between a multidisciplinary team. This article provides a summary of our key understandings concerning HS, for the purpose of increasing knowledge of this burdensome disease.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Although its pathophysiology has not been fully elucidated, HS is defined as an auto-inflammatory disorder involving an aberrant immune response occurring after the occlusion of hair follicles (Sabat et al., 2020). Follicular occlusion leads to intrafollicular propagation of bacteria and immune cell infiltration, accompanied by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, namely TNF-alpha, IL-17 and IL-1.

Dilated hair follicles may rupture, causing the spread of inflammatory infiltrates and the formation of an inflammatory nodule or abscess. Granulocyte activity leads to pus formation, and T-lymphocyte and keratinocyte activity mediate epithelial hyperplasia. In advanced disease, pyogenic tissue destruction and the seeding of follicular epithelial stem cells leads to the formation of epithelialised sinus tracts and fistulas.

Multiple factors have been implicated in propagation of HS. A genetic component is highly likely, given that a positive family history is observed in approximately one third of patients (Ingram, 2016). Mutations in the gamma-secretase complex have been implicated, though these variants account for a small subset of patients and may indicate a possible polygenic mode of inheritance (Ingram, 2016).

Smoking is a lifestyle factor that is highly correlated with disease severity, and with active smokers being 13 times more likely to have HS compared to non-smokers (Acharya & Mathur, 2020; Revuz et al., 2008). This may be explained by studies showing that nicotine induces epidermal hyperplasia, increasing the rate of infundibular occlusion, and that it promotes inflammation by secretion of TNF-alpha and IL-1beta by macrophages, keratinocytes and TH17 cells (Bukvi Mokos et al., 2020; Deckers et al., 2014; Shah et al., 2017). Obesity is also implicated, with approximately 50% of patients being obese and 40% having metabolic syndrome (Sabat et al., 2012). This association might be explained by follicular shearing via mechanical friction between skin folds, the promotion of bacterial growth due to perspiration retention, and increased circulatory levels of pro-inflammatory adipokines (Krajewski et al., 2023). Finally, although their role remains unclear, sex hormones are implicated in the progression of HS, since patients most commonly develop symptoms only after the onset of puberty, and disease severity can vary according cycles of menstruation and pregnancy (Clark et al., 2017).

CLINICAL COURSE AND PSYCHOSOCIAL BURDEN

HS lesions are typically distributed to the intertriginous areas, most commonly the axillary, inguinal, perineal and submammary areas. The primary lesion of HS is a solitary nodule or abscess that is highly inflamed, which persists for weeks to months. These lesions, which develop at a median rate of two nodules/abscesses per month, can be accompanied by prodromal symptoms such as fatigue, paraesthesia and pruritus (Sabat et al., 2020). Over the course of months to years, abscesses may then expand or coalesce to form sinus tracts and fistulae productive of malodorous, haemoseropurulent discharge. Other chronic skin changes include erosions/ulcerations due to loss of epidermis, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and aberrant scarring, including hypertrophic scars, fibrotic bands and indurated plaques. In severe cases, recurrent fibrosis and re-epithelialisation can lead to induration, contracture and lymphoedema, and to the formation of intercommunicating sinus tracts, which involve deeper structures such as muscle, fascia, vasculature and internal viscera (Alikhan et al., 2009).

HS is a disease which tends to start early in life, in the late teens and early twenties, which exerts far-reaching effects upon physical, psychological and social wellbeing (Goldburg et al., 2020). HS lesions cause significant pain, pruritus and malodour, which result in chronic disability (Matusiak, 2020). HS has a strong association with comorbidities such as smoking, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, spondyloarthropathy and Crohn’s disease (Zouboulis et al., 2019). Psychologically, HS patients have an increased risk of depression and anxiety, scaling with degree of disease severity, and also have more than double the risk of suicide than those with psoriasis (Tiri et al., 2018).

Socioeconomically, HS patients are significantly disadvantaged, due to the impact upon self-esteem, sexual function, fitness for employment and healthcare costs associated with continual medical and surgical interventions (Kirby et al., 2014). A recent study by our research group found that the burden of HS on quality of life not only exceeds that of other skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, but also of non-dermatological conditions such as myocardial infarction, lower limb amputation, chronic stroke and chronic hepatitis C (Mortimore et al., 2022). Far more than a mere skin condition, HS can critically affect the trajectory of a person’s life, invading into social wellbeing, romantic relationships and professional life.

DIAGNOSIS AND ASSESSMENT

Hidradenitis suppurativa is diagnosed clinically. In the European S1 guidelines (Zouboulis et al., 2015), primary positive diagnostic criteria include a history of recurrent painful or suppurating lesions in the inverse regions of the body, occurring more than twice in 6 months. Family history of HS is used as a secondary positive criterion.

Due to overlapping clinical features with other conditions, HS is often challenging to diagnose in its early stages. The differential includes follicular disorders including folliculitis, furuncules, carbuncles, simple abscesses, and infected Bartholin’s glands, as well as cutaneous Crohn’s disease, pyoderma gangrenosum and inflamed epidermal cysts (Sabat et al., 2020). Polyporous or complex comedones and sinus tracts are an important feature to support HS Dx over other condisitons such as recurrent simple abscesses. Histopathology typically serves to exclude alternative diagnoses, such as cutaneous Crohn’s disease, pyoderma gangrenosum and neoplastic skin conditions. Microbiology can be helpful for determining if there is secondary infection, however superficial swabs may show non-pathological staphylcocci, or normal skin microflora.

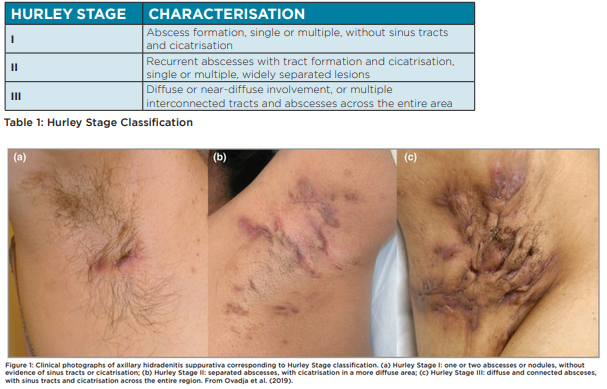

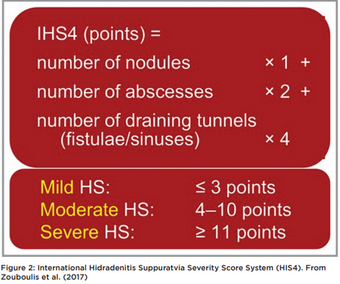

HS severity is most commonly classified using Hurley Staging (Table 1, Figure 1). Hurley classification is correlated to quality of life and in combination with patient-reported measures such as the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), may be used to guide treatment choices and monitor outcomes. Other severity measures used are simple AN count whereby a clinician counts abscesses (A) and nodules (N), or the International Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4) (Figure 2) (Zouboulis et al., 2017).

TREATMENT

The treatment of HS requires a holistic and multimodal approach, taking into account general measures, including lifestyle modifications, symptomatic control, wound cares and management of comorbidities, and disease-specific measures, including a variety of treatments, both medical and surgical. Treatment needs to be guided both by the type and severity of lesions as well as patient expectations.

There are several general measures to consider in the treatment of HS, including smoking cessation, weight loss, pain control, wound cares and assessment of comorbidities. With a strongly established positive correlation between HS and smoking and weight, both smoking cessation and weight reduction can play a crucial role in disease control (Denny & Anadkat, 2017; Kromann et al., 2014). Pain is typically the most troublesome symptom expressed by patients with HS, and this can be exacerbated by chronic inflammatory neuroplastic changes and mood disorders (Vural et al., 2019).

First-line analgesics include paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, with the cautious use of opioid analgesics during acute flares. In consultation with a pain specialist, these may be combined with anticonvulsants such as pregabalin and gabapentin for neuropathic pain, and antidepressants particularly where there is a comorbid mood disorder (Savage et al., 2021). Management of wounds is also an important intervention to reduce pain, in addition to minimising malodour, suppuration, maceration and secondary bacterial infection. Though dedicated HS-bandages are not available, the general principles are that dressings should keep the surface dry, absorb odour, reduce friction, and be shaped appropriately to anatomical location (Zouboulis et al., 2015).

Finally, HS management should include screening and appropriate referral for associated physical and psychological comorbidities, such as metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hypertension, depression and anxiety, inflammatory bowel disease, spondyloarthritis, polycystic ovarian syndrome and other follicular occlusion disorders (acne conglobata, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, pilonidal sinus).

Topical therapies for HS include skin cleansers, keratolytics, and antibiotics. These treatments are typically used as primary treatment in early stages of HS or as adjuncts to systemic treatment in later stages (Smith et al., 2018). Skin cleansers such as bleach baths, chlorhexidine, benzoyl peroxide and zinc pyrithione are used for their antiseptic properties and may have a role in reducing bacterial colonisation (Alavi & Kirsner, 2015).

Keratolytics such as resorcinol 15% in aqueous cream have an exfoliating effect aimed at reducing follicular occlusion, thereby targeting the primary event in the pathogenesis of HS (Boer & Jemec, 2010). Of the topical antibiotic therapies, clindamycin thus far is the only one with formal evidence supporting its efficacy (Clemmensen, 1983).

Oral antibiotic therapies are used in all stages of HS. Though they may be used in the control of acute infection, they are used for their immunomodulatory effects. However, they must be used with consideration of the risk of bacterial resistance. Oral antibiotics of choice include oral tetracyclines such as doxycycline, with the main adverse effects including gastrointestinal upset, photosensitivity and teratogenicity (Alikhan et al., 2019). Evidence also supports the efficacy of an oral combination therapy of clindamycin and rifampicin, particularly in Hurley stage II and III disease, with gastrointestinal upset, cytochrome p450 interactions and hepatotoxicity (Gener et al., 2009).

Hormonal treatments are sometimes used adjunctively, with varying success. In women who experience exacerbations in symptoms during menses, show signs of hyperandrogenism, or have concomitant polycystic ovarian syndrome, options include antiandrogens, oestrogens and spironolactone (Lee & Fischer, 2015; Sawers et al., 1986). Additionally, Metformin has demonstrated efficacy, and may be used in cases of insulin resistance and concomitant diabetes mellitus (Verdolini et al., 2013).

Corticosteroids are used sparingly in the treatment of HS. There is evidence to support the use of intralesional corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone 10 mg per mL, for reduction in erythema, size, suppuration and pain in acutely inflamed or treatment-refractory lesions (Riis et al., 2016). Systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone, hydrocortisone and dexamethasone, may be used in severe flares. However, while they will help pain and inflammation their side effects are prohibitive (Zouboulis et al., 2015).

In recent years, biologics have emerged as effective therapies for moderate-to-severe HS, particularly inhibitors of tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha). Adalimumab and infliximab are best supported for use in HS, although only the former has been approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration for use in HS (Lim & Oon, 2019). Further research is required to evaluate other biologics for treatment of HS and to identify new molecular targets of immunotherapy.

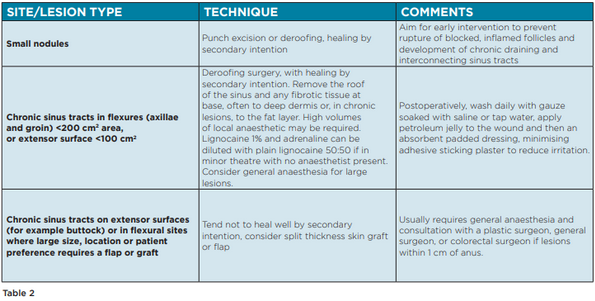

Surgical interventions for HS can be applied at all stages of disease, in tandem with pharmacological therapies. Procedures include incision and drainage, excision, deroofing, laser therapy, and electro-surgery. There are, however, no widely accepted guidelines to recommend the choice of surgical technique at each stage of disease. The Australasian Consensus Statement on the management of HS outlines a number of recommendations based on existing literature (Table 2).

CONCLUSION

HS is a condition with profound, long-lasting consequences on the patient. In this review it has been highlighted that a significant clinical issue is delay to diagnosis, which may partially arise from lack of recognition and awareness of the disease amongst medical practitioners. HS should be considered in any differential diagnosis of abscesses or nodules located in the flexural regions. Reducing misdiagnoses and subsequent time spent on futile treatments, is crucial in a disease where progression leads to irreversible tissue injury and disability.

It is furthermore evident that HS has wide-reaching influences on patients, thereby necessitating a comprehensive approach to care, with consideration not only for its metabolic and endocrine comorbidities, but its psychological and social sequelae. Therefore, general practitioners play a crucial part in ensuring optimal outcomes, by coordinating multiple specialties as part of a multidisciplinary philosophy of care. Treatment is currently complex and not clearly defined in algorithms determined by formal evidence. The aims of future research are to unravel the complex pathophysiology and genetic landscape of HS, and develop new molecularly targeted therapies capable of inducing disease remission.

Dr Timothy Liu is a senior house officer at Princess Alexandra Hospital’s Department of Dermatology, where he is also a hidradenitis suppurativa research fellow involved in multiple studies in collaboration with Dermatology Research Centre, the University of Queensland.

Associate Professor Erin McMeniman is a Brisbane dermatologist in private practice. She is also chair of the Queensland Faculty of Dermatology, chair of the Australasian College of Dermatology Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Committee and a member of the college’s Academic Research Committee. She is also a visiting medical officer at the Princess Alexandra Hospital’s Department of Dermatology.

REFERENCES

Acharya, P., & Mathur, M. (2020). Hidradenitis suppurativa and smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 82(4), 1006-1011.

Alavi, A., & Kirsner, R. S. (2015). Local wound care and topical management of hidradenitis suppurativa. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 73(5), S55-S61.

Alikhan, A., Lynch, P. J., & Eisen, D. B. (2009). Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 60(4), 539-561.

Alikhan, A., Sayed, C., Alavi, A., Alhusayen, R., Brassard, A., Burkhart, C., Crowell, K., Eisen, D. B., Gottlieb, A. B., & Hamzavi, I. (2019). North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: A publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: Part I: Diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 81(1), 76-90.

Boer, J., & Jemec, G. (2010). Resorcinol peels as a possible self treatment of painful nodules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Clinical and experimental dermatology, 35(1), 36-40.

Bukvi Mokos, Z., Miše, J., Bali, A., & Marinovi, B. (2020). Understanding the relationship between smoking and hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Dermatovenerologica Croatica, 28(1), 9-13.

Calao, M., Wilson, J. L., Spelman, L., Billot, L., Rubel, D., Watts, A. D., & Jemec, G. B. (2018). Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS) prevalence, demographics and management pathways in Australia: A population-based cross-sectional study. Plos one, 13(7), e0200683.

Clark, A. K., Quinonez, R. L., Saric, S., & Sivamani, R. K. (2017). Hormonal therapies for hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology online journal, 23(10).

Clemmensen, O. J. (1983). Topical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with clindamycin. International journal of dermatology, 22(5), 325-328.

Deckers, I. E., van der Zee, H. H., & Prens, E. P. (2014). Epidemiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: prevalence, pathogenesis, and factors associated with the development of HS. Current Dermatology Reports, 3, 54-60.

Denny, G., & Anadkat, M. J. (2017). The effect of smoking and age on the response to first-line therapy of hidradenitis suppurativa: An institutional retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 76(1), 54-59.

Gener, G., Canoui-Poitrine, F., Revuz, J., Faye, O., Poli, F., Gabison, G., Pouget, F., Viallette, C., Wolkenstein, P., & Bastuji-Garin, S. (2009). Combination therapy with clindamycin and rifampicin for hidradenitis suppurativa: a series of 116 consecutive patients. Dermatology, 219(2), 148-154.

Goldburg, S. R., Strober, B. E., & Payette, M. J. (2020). Hidradenitis suppurativa: Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 82(5), 1045-1058.

Ingram, J. R. (2016). The genetics of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatologic clinics, 34(1), 23-28.

Kirby, J. S., Miller, J. J., Adams, D. R., & Leslie, D. (2014). Health care utilization patterns and costs for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA dermatology, 150(9), 937-944.

Kokolakis, G., Wolk, K., Schneider-Burrus, S., Kalus, S., Barbus, S., Gomis-Kleindienst, S., & Sabat, R. (2020). Delayed diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa and its effect on patients and healthcare system. Dermatology, 236(5), 421-430.

Krajewski, P. K., Matusiak., & Szepietowski, J. C. (2023). Adipokines as an important link between hidradenitis suppurativa and obesity: a narrative review. British Journal of Dermatology, 188(3), 320-327.

Kromann, C., IBlER, K. S., Kristiansen, V., & Jemec, G. B. (2014). The influence of body weight on the prevalence and severity of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta dermato-venereologica, 94(5), 553-557.