If deep learning can master difficult things like chess, general practice should be a piece of cake.

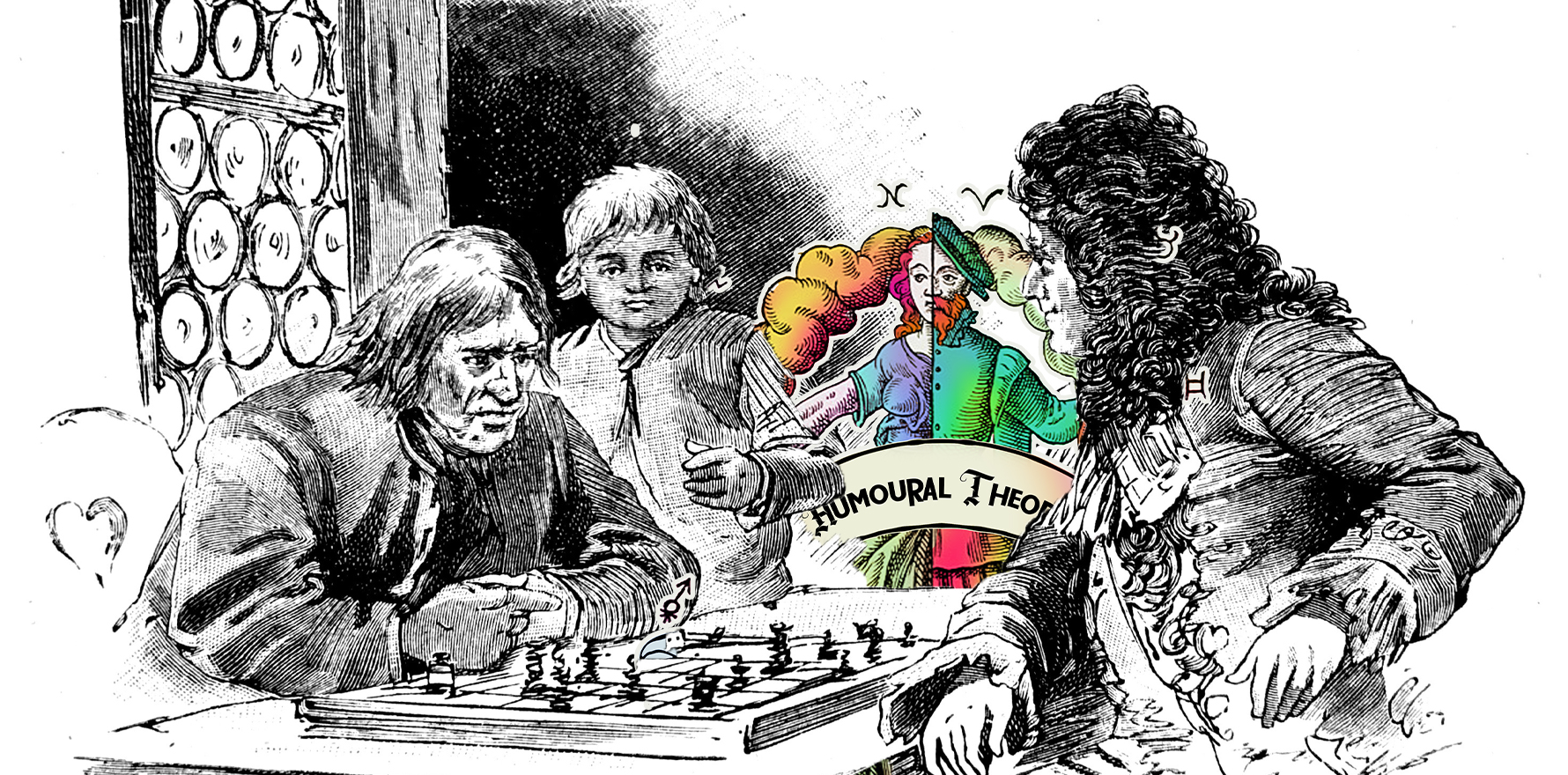

GK Chesterton wrote: “Imagination does not breed insanity. Exactly what does breed insanity is reason. Poets do not go mad; but chess-players do.”

Two great chess players are currently fighting it out in Dubai: Magnus Carlsen the Norwegian genius, with the highest ranking in the history of the game, is battling against his Russian contemporary Ian Nepomniachtchi for the world chess championship.

“Ever since IBM’s Deep Blue was able to beat Garry Kasparov, computers have gone from strength to strength,” says Professor Candid.

“There are more games of chess up to move 40 than there are atoms in the visible universe – a bit like a general practice appointment. If machine learning can nail one of them, why not the other?”

Using deep learning Ais AlphaZero and AlphaGo as a model, Prof Candid and his team developed “AlphaMedico”.

“AlphaMedico works like your standard GP,” the professor explains. “It recognises patterns, it uses rules of thumb or heuristics and it makes decisions based on probabilities – in short, it’s developed clinical intuition.

“Unlike GPs though, it doesn’t need a toilet break, it doesn’t hanker after a ham and cheese sandwich and it won’t complain about the amount of tax it has to pay. At least not yet.”

TMR spoke with some of AlphaMedico’s patients.

“I was a little nervous at first,” admits 32-year-old single mum Emma Earnshaw. “When I walked into the consulting room it was empty except for a computer trolley and the only light came from the glowing green screen of a computer monitor. The computer asked me lots of questions and then went quiet for a minute or two – I thought there’d been a power cut but it came to life and printed out a diagnosis and management plan.

“I was impressed but if I’m honest I was relieved to get out of there.”

“Unlike other GPs I’ve seen over the years,” said Bethany Bubbles, 40, “it was able to identify the cause of my chronic pelvic pain. But at the end of the day AlphaMedico is just a fancy box with flashing lights. As far as I’m aware it doesn’t even have a pelvis and so when it told me it knew where I was coming from and that it could feel my pain, I just didn’t buy it.”

Jacqueline Joyce, a 58-year-old carer, said: “He diagnosed my mother’s breast cancer and I was so grateful that I went back to see him with a box of chocolates. I gave him a hug, which felt a bit weird because I’ve never really hugged a computer before, but I think he quite liked it.

“Apparently his visual recognition software isn’t set up for Cadbury’s Roses, so I unwrapped one and pushed it through one of his little vents. Unfortunately it buggered up his motherboard and the Professor had to spend a couple of days tweezering out melted toffee from his circuits.”

“The great thing about AlphaZero and AlphaMedico is that they learn and evolve over time,” says the professor.

“But AlphaZero doesn’t really know when it’s won a game of chess and AlphaMedico doesn’t really know when it’s got the right diagnosis.

“It can’t fist bump and it can’t go out and celebrate with a cocktail. Equally, when it gets the wrong diagnosis it doesn’t suffer like a real GP – and it’s the suffering that matters, it’s the suffering that really connects us.”

To go back to the chess analogy, he concludes, “AlphaZero may well be able destroy the greatest human players alive but it will never suffer a single day for its greatness. And if the grandmasters of the past are anything to go by, players like Wilhelm Steinitz, Bobby Fischer and Paul Morphy, then genius often descends into the murky half-light of madness.”

As Chesterton said, too much rationality can in some cases breed insanity, but it’s our frailty and our ultimate demise that makes us human.