Post-discharge prescribing varies depending on whether the patient had a bypass or angioplasty with stent.

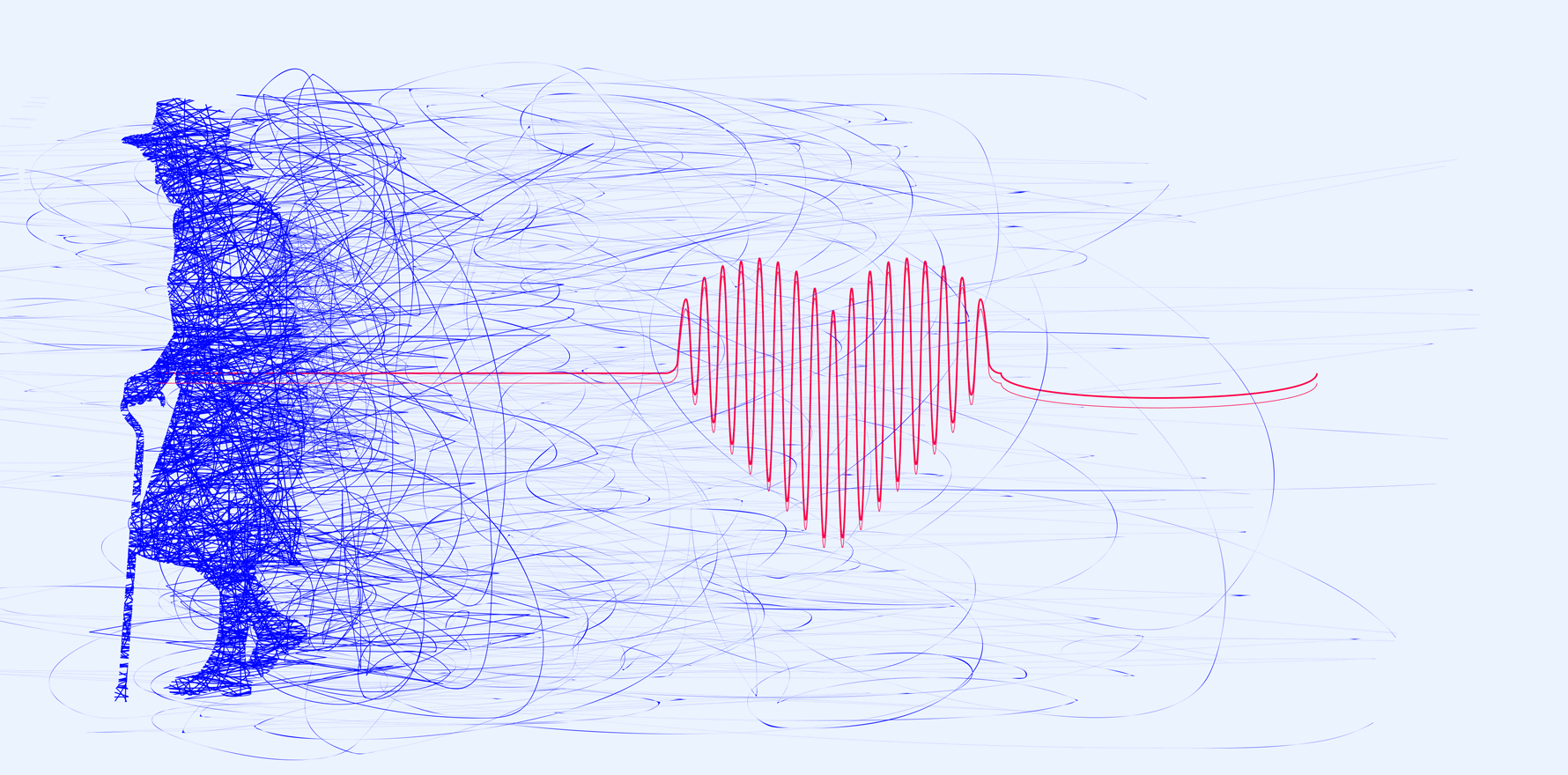

Patients with acute coronary syndrome are being prescribed different medications depending on the intervention used to restore blood flow, a Victorian study shows.

This is despite guidelines recommending the same secondary prevention drugs regardless of whether they’ve had an angioplasty with stent (called here percutaneous coronary intervention or PCI) or a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG).

The choice of revascularisation strategy depends on factors including coronary anatomy, whether there is single or multivessel disease, comorbidities and patient preference, according to the study published in Heart Lung and Circulation.

The researchers, from Monash University’s pharmacy faculty, looked at all hospital admissions for non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction between 2012 and 2017. They were seeking to confirm findings of smaller studies that bypass patients were less likely to be prescribed the recommended medications.

Out of the more than 15,000 NSTEMIs during that time, three-quarters were revascularised with the less invasive PCI), while the rest underwent a CABG.

Using linked data, the team recorded initial dispensing and 12-month subsequent use of antiplatelet drugs (P2Y12 inhibitors), statins, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACEi)/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and beta blockers.

For initial dispensing, the largest difference between the groups was with antiplatelet drugs, which were dispensed in 94% of PCI cases and only 17% of CABG cases.

Overall statin use showed no difference (89% for both) but high-intensity statins were given to more bypass patients (69%) than those who had undergone PCI (60%).

With ACEis/ARBs the proportions were 69% and 42% in the PCI and CABG groups, respectively, while for beta blockers they were 59% and 69%.

The data for 12-month use showed the same patterns (with slightly lower proportions all round), suggesting the prescribing decisions made at discharge tend to be maintained throughout the post-discharge period.

The differences, the authors supposed, may arise “because post-discharge prescribing decisions are made by different treating teams according to the revascularisation strategy, suggesting that in-hospital cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery teams may prescribe differently”.

More specifically, the low use of antiplatelet drugs among bypass patients might reflect a less robust evidence base in this group, but could also be due to greater complexities around blood-thinners with the surgical option.

The lower use of ACEi/ARBs in the bypass group was despite these patients having “a higher prevalence of comorbidities where greater benefits of these drug classes have been observed”, but might be happening due to higher levels of postoperative hypotension and kidney dysfunction in CABG patients.

The higher initial use of beta blockers could be due to the higher prevalence of heart failure and atrial fibrillation among patients undergoing bypass than PCI, they wrote, noting an emerging evidence base that “no longer supports the routine use of beta blockers following NSTEMI in the absence of left ventricular dysfunction”.

Related

The Heart Foundation’s chief medical advisor Professor Garry Jennings, told TMR this was “an important study drawing attention to the need for long-term evidence-based therapy after acute interventions for coronary heart disease”.

The fact that the medications recommended by the Heart Foundation and international guidelines were dispensed less frequently after bypass surgery than after angioplasty and stent was “both disappointing and remediable, especially with further examination of the root causes,” said Professor Jennings, who is also a clinician and researcher at the Baker Institute and The Alfred.

“These might include differences in patient characteristics and status at the time of discharge, local protocols and monitoring, communication between acute and primary care.

“A new NHF/CSANZ guidelines on acute coronary syndromes will be released later this year. It is unlikely these recommendation for post discharge medications will change much and this might be one area of focus during guideline implementation.”

Under study limitations, the authors conceded their dataset was getting old and that it could not distinguish between a clinician’s decision to withhold a drug and a patient’s decision not to fill a prescription.