It’s not faceless bureaucrats but doctors who are the harshest judges. The quest for reform must start elsewhere.

Grey’s Law tells us that “Any sufficiently advanced incompetence is indistinguishable from malice”.

Those words seem uniquely well attuned to health practitioner regulation, because the decisions can have such substantial and adverse effect on an individual, practitioners feel that the decision must be personal and the result of some sort of deliberate malice.

That could not be further from the truth.

The better explanation is a combination of the difficulty of the job, combined with government inefficiency and ideological differences, and with some incompetence sprinkled in for flavour.

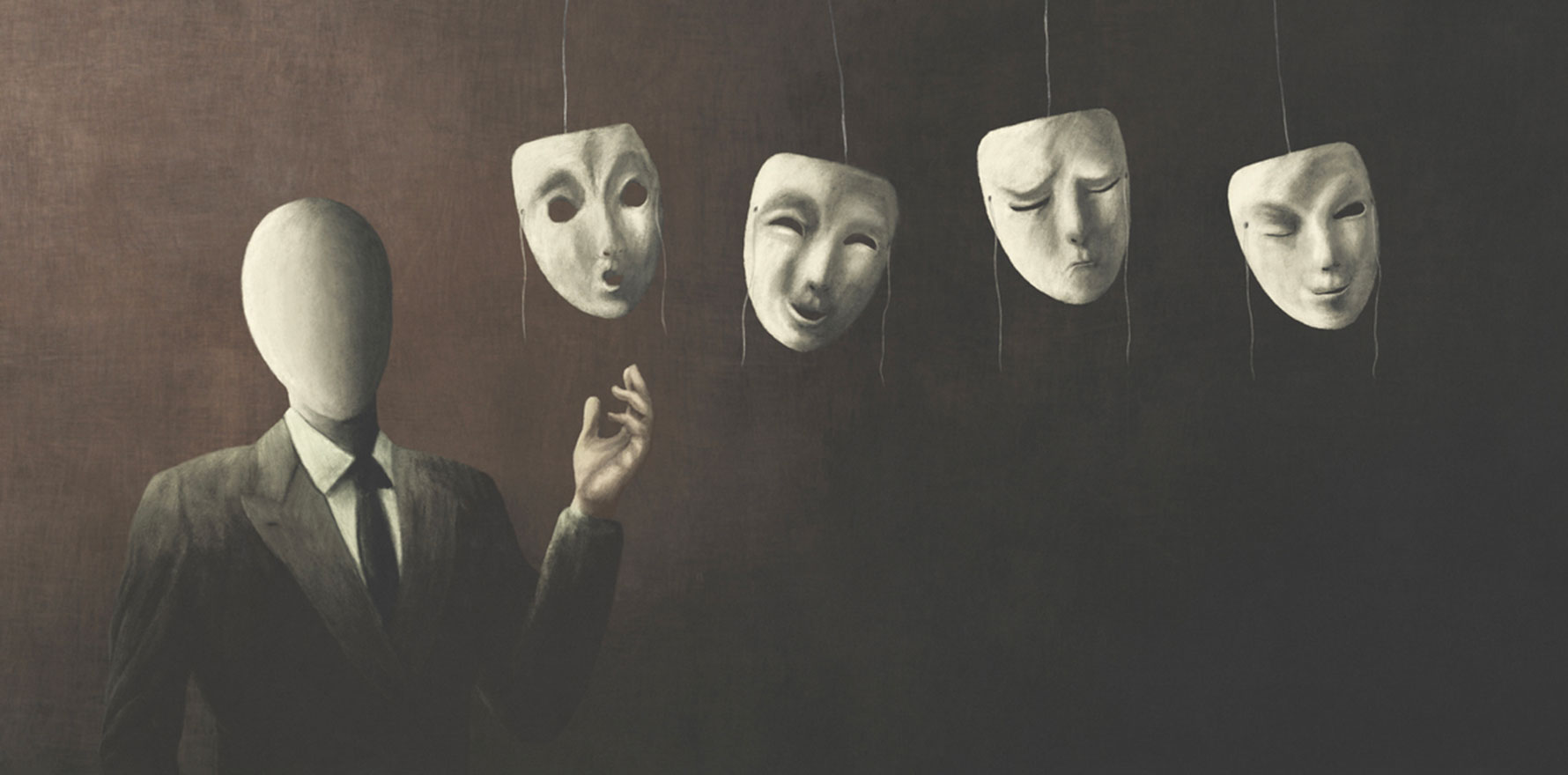

It is also because you are a faceless name on a spreadsheet. You are an invisible person whose entire existence has been boiled down to a handful of issues that have been “identified for investigation”.

You are not a human, you are a notification number.

It is not that the system is tainted by hatred, malice or bias – rather, it is that the system is not human enough. Sometimes when I read outcome letters from AHPRA, it feels very much like ChatGPT has determined the outcome, because it feels so impersonal and so detached from the individual whom it concerns – a practitioner who I know to be caring, skilled, and thoughtful.

The reason why I say all of this is that so often I see people advocating for things that won’t fix the system at all. To know what sorts of reforms might work, we need to accept a few truths before we can move forward.

Most of the decision-makers are doctors

There are exceptions, such as the Ombudsman and the Health Care Complaints Commission, where decision-makers may not be doctors – but the medical boards are always comprised primarily of doctors.

They are not bureaucrats. Seeking to put power back in the hands of doctors will not work, because the power is already in the hands of doctors.

Doctors are the harshest decision-makers about other doctors. Some apply impossibly high standards to their colleagues, and do so without any legal training that might assist in making their decision-making more impartial and fair.

Related

Regulators think they are doing the right thing

This applies to all regulators – the staff at AHPRA (I have been one) and the decision-makers on medical boards believe that they are doing the right thing. They want to help and they want to protect the public. They are not doing this out of malice, or to harm doctors.

This is really important to know. Often people threaten to go to the media with something that AHPRA has done – but this is never effective against someone who believes they are doing the right thing. If you have done something good, why would you care if someone runs to the media about it?

I say this as I have been the person on the other end of the phone with an upset practitioner telling me I had bad intentions and was trying to cause them harm. When they told me I was “a shill for Big Pharma” (sadly my cheques must have been lost in the mail), I would simply switch off – because I knew that this was not true. I was there because I believed what I was doing was for the benefit of society. The same is true of almost all of my former colleagues there. I can assure you – it is very rare that anything that AHPRA or the Medical Board do is as a result of actual malice.

Rarely it will happen, typically with higher-profile matters. The case of Dr William Bay is a good example of where there appears to be a level of deliberate targeting (the Supreme Court found that there was an “animus” towards him), and I will be writing about that case soon – but it is the exception, and not the rule.

The system does a lot of good

I have previously written about this, but it’s important to remember. The National Register is one of the most advanced public registration systems for health practitioners in the world.

The vast majority of registration matters are dealt with very quickly. Most notifications have the appropriate outcome, in a reasonably timely manner. Our health regulation system is one of the safest in the world.

These successes mean that we should not simply burn the whole thing down and start again – we did that already with the state-based boards in 2010. If AHPRA is abolished, something else will need to rise in its place – and then that regulator will take many years to work out what its job is and how to do it (AHPRA has been in place for 15 years and often still does not know what it is doing).

The system cannot deal with complex matters

Complex matters are the ones that damage the whole system. Many performance matters are complex, and they are the ones that I have observed as being the most problematic.

For example, it can be exceptionally hard to determine whether a complication that arises in surgery is the fault of the practitioner or not. I have seen matters where experts line up on both sides and give unequivocal evidence that the practitioner is absolutely at fault, and that the practitioner is absolutely not at fault. What is a regulator to do in that circumstance?

Ideology plays a major role

If there is a particular approach to an area of medicine that is favoured at board level, practitioners who disagree with that approach and use another approach are likely to be treated far worse than others.

This leads to ideological “wars”, such as the forceps vs vacuum debate in obstetrics.

This means that practitioners who practise in certain areas of medicine, or in certain ways, are far more likely to suffer adverse outcomes because they do not have a seat at the table.

So what do we do?

I propose that we focus less on the people involved in the system, and more on the system itself.

We should look at the specific outcomes that we find problematic, and work through what kind of systemic changes will fix those problems – rather than focusing on the individual people making decisions.

This makes finding solutions much harder, because we cannot simply replace individuals in power – but my hope is that by attacking the root systemic causes of the problem, we will be able to effect change that is lasting, and can help remove the fear that practitioners feel when they see an email from AHPRA land in their inbox.

I’d be interested to know what you think are the most problematic outcomes that we need to tackle. For me, it is delay (which I wrote on a few weeks ago), weaponisation of complaints, and the poor management of performance-based matters – but let me know your thoughts in the comments!

David Gardner is a lawyer, and a former manager and investigator at AHPRA. In addition to his legal practice, he is the director of AHPD, a new CPD provider of high-quality education to doctors on largely neglected non-clinical topics.