Sceptics are debunking the ancient Chinese practice of acupuncture as a credible medical therapy

Sceptics are debunking the ancient Chinese practice of acupuncture as a credible medical therapy

There is no place for acupuncture in medicine, and decades of research and thousands of studies are more than enough to conclude that acupuncture doesn’t work, says the Australian sceptic group, Friends of Science in Medicine.

“It is merely a theatrical placebo based on pre-scientific myths.”

The science advocacy group, led by Professor John Dwyer AO, emeritus professor of medicine at the University of NSW, recently singled out acupuncture as a therapy to be added to the NHMRC’s list of alternative therapies without any credible evidence.

Professor Dwyer and colleagues called for the inclusion of acupuncture alongside homeopathy, iridology and reflexology, to the list of treatments for which subsidies should be ended in a time where money is being cut from other evidence-based therapies.

Their review of the evidence traces acupuncture’s history and growth in Western countries, ultimately concluding that it has no place in 21st century medicine.

“Acupuncture has been studied for decades and the evidence that it can provide clinical benefits continues to be weak and inconsistent,” says the group, adding that any healthcare practitioners who base their treatment on credible evidence should abandon acupuncture, if they haven’t already.

The popularity of acupuncture has risen rapidly in Australia and other Western countries, in part because it is seen as a low-risk and time-tested intervention.

There are five different MBS item numbers for acupuncture therapy, depending on whether the practitioner is a GP or not, and where the consultation took place.

But while the rate of consultations has been steadily dropping, now at 520,561 a year, down from 719,194 in 2000, the overall cost of the treatments to the taxpayer has actually increased.

In 2000, the government was paying $15.2 million for acupuncture consultations. But in the last financial year, this number had risen to $24.7 million.

WHAT IS IT?

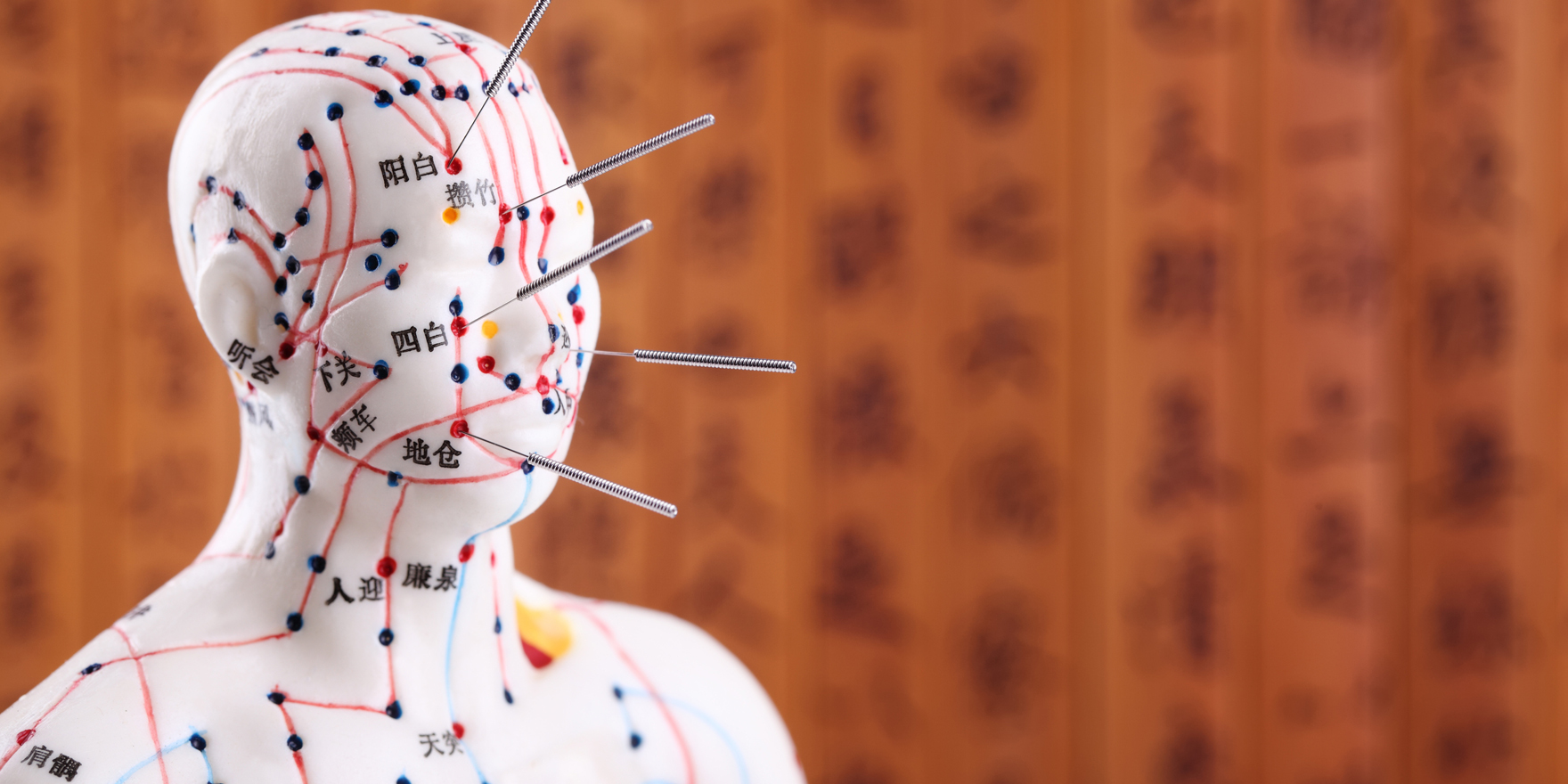

Acupuncture involves inserting fine needles into specific acupuncture points, which are said to be along the body’s so-called meridian points.

The meridians are supposed to channel the body’s vital life-force, or “qi”, throughout the body, and acupuncture “clears any blockages” that are causing the patient’s illness or discomfort.

The Australian Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine Association, the peak professional body for acupuncturists, say the practice can help with a wide range of neurological conditions, from headaches to stroke.

On the respiratory front, acupuncture is said to benefit conditions ranging from sore throat to acute tonsillitis and bronchial asthma. Gingivitis, constipation, gastritis, enuresis, painful or heavy menstruation, prolapse of uterus or bladder, infertility, acne, cataracts, sciatica, back pain and a range of psychological conditions are all also within the realms of treatment for acupuncturists.

But there are just about as many suggested indications for acupuncture as there are illnesses.

And the type of acupuncture can vary significantly. Some therapists use electricity, low energy laser beams, or burning Moxa, also known as Mugwort, with the procedure. Some therapists focus solely on the ear, or hands and feet.

While part of the appeal of acupuncture is that it’s an ancient technique, the claim that it’s 2000 to 5000 years old is disputed.

Acupuncture isn’t mentioned in the earliest Chinese medical texts, dated 200 years BCE. The first reference to acupuncture appears to be in the Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine which was written 100-200 BCE, according to Friends of Science in Medicine.

At the time, only 160 acupoints, or energy points where needles should be inserted, had been described. Now, there are more than 2000 acupoints described by various acupuncture practitioners.

“If you add up all the acupoints described in all the different systems of acupuncture, it’s hard to find an area on the skin that has not been designated as an acupoint,” the sceptic group’s authors say.

The key criticism is that the evidence for acupuncture is almost always from small trials and the effect size is small, if present at all.

“Almost all trials of alternative medicines seem to end up with the conclusion that more research is needed. After more than 3000 trials, we should recognise that the need for more trials is dubious,” the group says.

The highest quality studies done on acupuncture suggest that needles can be inserted anywhere, and in fact the needle doesn’t actually have to pierce the skin to provide an effect, say the authors.

“The one thing that does seem to matter is whether the patient believes in acupuncture.”

Professor Robert T. Carroll, publisher of The Sceptic’s Dictionary, puts it thus: “I must state up front that those sceptics who say that acupuncture doesn’t work, or that it is not an effective medical treatment for some ailments, are wrong.”

Personal testimony and scientific studies both clearly show that it is effective for some ailments, however, scientific studies also clearly show that sham acupuncture is just as effective as true acupuncture, he says.

Evaluating acupuncture is more difficult than pharmacological interventions, in part because of the numerous different types and techniques of acupuncturists, but also because of difficulties blinding the participants and therapists to the group they are in.

The best available option to tease out the placebo effect is to use a device that has a retractable needle in a sheath. Patients receiving these are unable to discern the difference between the real intervention and the sham one.

But this doesn’t fool the acupuncturist, who will still be aware of which therapy they are giving to the patient. And because of this awareness, it’s not possible to perform a double-blind experiment. When the practitioner knows whether they are in the “real” intervention arm or not, there is always the risk that they will behave differently, even if subconsciously.

The question of whether acupuncture works comes down to two key elements: Does it work on the principles acupuncturists say it does? Or does it have any beneficial effects regardless?

The most popular claim is that acupuncture can help relieve pain.

One high-quality study of 1100 patients with chronic back pain compared the benefits of acupuncture, sham acupuncture and combined medical, exercise and physical therapy.1

It didn’t matter whether the patients were treated with needles in traditional acupuncture points and with traditional methods, or if they were inserted in non-traditional spots and weren’t twirled or inserted as deeply – both groups had twice as much pain relief as the non-needle group.

Another study from Sweden in 2011 used a different type of sham acupuncture, with needles that retracted on the skin.2

The 215 patients being treated with radiotherapy for cancer were tested to see if acupuncture relieved nausea.

There was no statistical difference between duration or extent of sickness between the groups, and both groups were similarly positive about having “acupuncture” again.

This has led sceptics to conclude that there is no basis for the underlying concept of meridians that channel “qi” around the body, or that they can be unblocked by needle insertion in specific areas.

But some studies have explored the potential biochemical mechanisms underlying acupuncture. One widely publicised animal study from the Nature journal, Neuroscience, suggested that the pain-relief from acupuncture was thanks to the release of adenosine, a chemical believed to ease pain by reducing inflammation.

The study found that acupuncture needles inserted into mice triggered a release of adenosine from surrounding cells into extracellular fluid that lessened the pain felt by the animals.

Injecting the mice with compounds similar to adenosine was found to have the same effect as acupuncture.

The authors concluded that this study showed “that adenosine is central to the mechanistic actions of acupuncture”.

This study was widely reported as confirmation of the scientific basis for acupuncture, but Professor David Gorski, an American surgical oncologist, trashed the uncritical positive coverage in an article on the site, Science-Based Medicine3.

Instead, ear piercing or twirling a toothpick against the skin can also offer the same relief as needling, but the authors failed to test this, he argues.

There’s also nothing to suggest that certain points are more effective than others in the body for pain relief, he says.

“There are two remaining huge problems with this paper,” according to Professor Gorski. “Mice are much, much smaller than humans. The Zusanli (acupuncture) point in a mouse is going to be within a couple of millimetres of the sciatic nerve or one of its major branches.

“In the human, it’s going to be at least a couple of centimetres away, possibly considerably further. In the mouse, the size of the needle relative to the size of the leg and distance from the sciatic nerve, as well as the nerve’s branches, the tibial and peroneal nerves, is going to be very close.

“The tissue damage, virtually no matter where the needle is stuck, is going to be close to these nerves,” he says, adding that it would be unlikely these results would translate to humans unless we wanted to start sticking nails into people’s knees.

The study provides no insight on chronic pain, or other illnesses, including nausea, headache or fertility, he says.

Another well-publicised study published in the British Journal of General Practice explored the effectiveness of acupuncture in treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms – and was criticised for putting a positive spin on what was ultimately a negative finding.

The researchers studied 80 patients who had been seeing their GP eight or more times a year4, and found that those who underwent acupuncture had improved scores on a self-report questionnaire about their symptoms.

The authors concluded that 12 sessions on top of usual care “improved health status and wellbeing that was sustained for 12 months”.

But UK evidence-based practice consultant, Michael Power, points out that the difference was only 0.6 on the 7-point wellbeing scale, and the patients, practitioners and study organisers knew which trial arm the patients were in.

Professor David Colquhoun, UK pharmacologist and acupuncture sceptic, is highly critical of the positive coverage of the article, saying the study results show the opposite of the authors’ conclusion.

“This paper, though designed to be susceptible to almost every form of bias, shows staggeringly small effects. It is the best evidence I’ve ever seen that not only are needles ineffective, but that placebo effects, if they are there at all, are trivial in size and have no useful benefit to the patient in this case,” Professor Colquhoun says.

This year, two of the Cochrane reviews came out largely positive towards pain relief for tension-type headaches and migraine prophylaxis.

In six trials, headache frequency halved in 52% of the patients in the acupuncture group compared with 43% in the sham acupuncture group. In 15 trials, the frequency of migraines halved in 50% of those receiving true acupuncture and 41% in the sham acupuncture group, the Cochrane reviews found.

In separate evaluations, Cochrane reviewers found no benefit for fertility, chronic back pain, period pain, depression, insomnia, chronic asthma or a number of other illnesses.

In response to the sceptic group’s calls to scrap support for acupuncture, Dr Bill Meyers, president of the Australian Medical Acupuncture College, argues that dismissing acupuncture based on comparisons with sham techniques is a mistake.

Instead, literature shows that sham needle acupuncture is an active treatment with neurophysiological effects, he says.

“This scientific fact then renders many past negative studies of acupuncture understandable, including many considered by the Cochrane Collaboration,” Dr Meyers says. “The studies were comparing often inadequate acupuncture treatment (such as a single acupuncture point, or a few treatment sessions) with physiologically active sham acupuncture. This rendered conclusions of acupuncture’s ineffectiveness not proven.”

HARMFUL EFFECTS

While acupuncture has very few reported side effects, there have been adverse events. An Olympic Judo champion from Canada suffered a collapsed lung after an acupuncture needle accidentally pierced her left lung, and a middle-aged Korean woman received a life-threatening cardiac tamponade after an acupuncture needle was stuck directly into her right ventricle.

Some worry that acupuncture and other alternative medicines may also divert people away from mainstream medicine or delay evidence-based medicine.

But looking at data from the 2008 census shows that almost half of all those who saw an acupuncturist in the previous two weeks had also been to visit a doctor in that time. This suggests they are still in contact with mainstream medicine, although they may be visiting about different problems or not fully overlapping.

With the Medicare Benefits Schedule Review Taskforce set to begin its investigation into acupuncture later this year, the spotlight will be on whether the evidence in support of the therapy is enough to justify its ongoing inclusion for subsidies.

References:

1: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=413107

2: http://annonc.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/09/23/annonc.mdr402.full

3: https://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/another-overhyped-acupuncture-study-misinterpreted/