A famous study on inattentional blindness has been given another look.

First they came for Zimbardo’s prison guards, then Milgram’s obedient torturers; now they’ve come for the invisible gorilla.

Yes, one of the most widely popularised experiments in psychology is getting some renewed, ahem, attention.

This isn’t a case of failure to replicate due to the WEIRD characteristics of the original test subjects. It’s that they’ve thrown in an important variable: speed.

In the original 1999 study into inattentional blindness, participants had to watch a video of people passing a basketball and count the number of passes among members of one team or the other, then were asked whether they’d spotted a gorilla mooching in and out of the frame.

Detection rates were poor, but varied greatly by team. Only 8% of those counting passes by the team in white detected the gorilla, while 67% of those counting the team wearing black did.

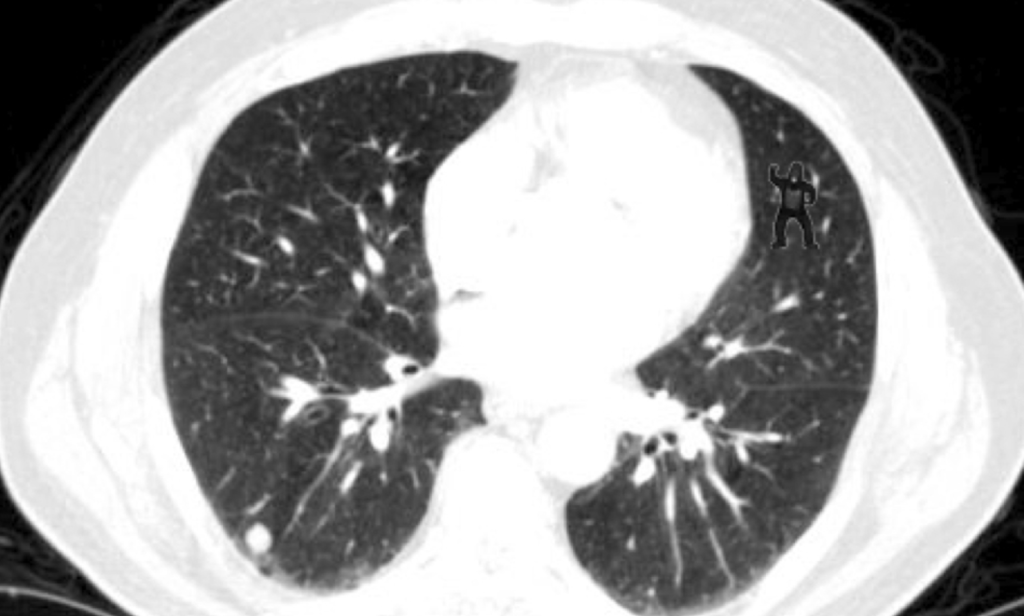

In 2013 a different team asked radiologists to look at the CT scan below, in which they’d hidden (in allusion to the 1999 study) a little waving gorilla:

A full 20 of the 24 hapless radiologists missed it.

The studies have been interpreted to mean that focusing on one task brings the inevitable downside of blindness to objects that fall outside that task.

In a new study in PNAS, a team from New York University set out to reconcile this widely accepted conclusion with the evidence that people can in fact be distracted from tasks by unexpected stimuli – “that goal-directed endogenous and stimulus-driven exogenous attention may compete in dynamic environments”.

Suspecting that the original researchers used stimuli that weren’t dynamically strong enough – their gorilla is slow and walks upright – they recreated the passing video with a gorilla impersonator that moves faster and more like an animal.

They found again that those focused on the black-wearing players did much better at spotting the interloper than those watching white. For the latter, speed made a big difference in detection rates, while for the former the detection was already so high it was hard to find a difference.

The authors note an important limitation: “due to the overwhelming popularity of the original results, it is now hard to recruit truly naive participants”. When they reused the original video, detection rates were much higher: around 60% for the white team and over 90% for black.

To bypass this problem they nixed the primate and had subjects count moving dots on a screen while an unexpected object traversed the screen at various speeds. Again they replicated Simons & Chabris’ white/black difference.

Detection rates ranged from just 21% in the white condition when the object moved at the same speed as the dots, up to nearly 100% for black when the object moved 5x faster.

They conclude that we’re capable of some inattentional blindness while focusing on an important task, but a fast-moving object can override that focus.

We wouldn’t have come very far in our evolutionary journey if this weren’t the case: you want to be able to focus on picking berries and not be distracted by every caterpillar, but you can’t afford to miss the charging silverback.

Send story tips to penny@medicalrepublic.com.au to improve your situational awareness by 30%.