A molecular biologist and musician 'plays' the coronacode.

All my life I’ve been involved in music and molecular biology. At the crossroads between science and art, I see great scope for insight.

My latest research, published in the journal BMC Bioinformatics, reveals how music can be used to reveal functional properties of the coronavirus genome.

This project followed earlier work I had done generating audio from human DNA sequences; this time, I wanted to apply those techniques to the virus sweeping the world to see what might be revealed. In other words, this was the difficult second album!

Read more:

What does DNA sound like? Using music to unlock the secrets of genetic code

Assigning notes to the ‘words’ in the genome

Genes of the coronavirus are like biological book chapters; they hold all the words that describe the virus and how it might function. These “words” are made from strings of chemical letters scientists refer to as G, A, U and C.

This viral “book” is over 30,000 characters long. Some of these characters come together to form what scientists call a codon, which is a sequence of RNA that corresponds to a specific amino acid. But to stick with our analogy, let’s just say they come together to form “words”.

In my work, I assigned notes to these words to generate audio; I had wondered if this might helps us understand what the words mean.

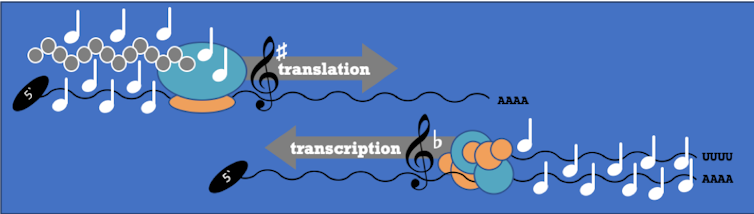

I devised an online tool to hear the sound of coronavirus doing two things most genomes do: the first is called “translation”, which is where the virus makes new proteins. The second is called “transcription”, which is where the genome of the virus copies itself.

There are several things you can hear: the start and end of genes, the regions between genes and the parts of the genome that control how genes are expressed.

Other researchers have written about this extensively in the coronavirus scientific literature but this is the first time you can distinguish between these regions by listening.

Revealing relationships between structure and function

So, what’s the point of all this?

As a research tool the audio helps supplement some of the many visual displays that exist to represent genomic information. In other words, it helps scientists understand even more about the virus and how it operates. Recently, UK-based composer and researcher Eduardo Miranda at the University of Plymouth used DNA sequence data for music composition and to better understand synthetic biology. Researcher Markus Buehler at MIT has been working with musical representations of proteins to enquire about novel protein structures.

I think an equally valid question is: does the audio sound musical? Now that I have finished the scientific research part of this project, I listen to the coronavirus genome with fresh ears, and from a musician’s perspective I been surprised as to how musical it sounds.

I don’t mean to trivialise the pandemic by thinking about the virus in musical terms.

As a molecular biologist at Western Sydney University, when I think about the virus I see RNA sequences, and it’s my job to see relationships between structure and function. I don’t see patients in the clinic and I’m not researching a cure — these things are not my domain.

Taking the genome to the recording studio

As a musician, I have also taken the audio data into the recording studio, away from the research lab, to reveal other perspectives on the coronavirus.

The coronavirus audio is pulsating and incessant, but, working with other musicians, we have tried to tame the sequence; to make it subservient to our musical knowledge, ideas and human spirit.

I returned to the trusty drum kit that once drove my old band The Hummingbirds and this now beats the viral sequence into submission. With guitar by Mike Anderson, who is in Sydney-based instrumental surf twang band Los Monaros, we have reached an understanding of its jagged rhythms and syncopated pulses to create some music.

Author provided, Author provided

We mixed the computer-generated audio from the coronavirus genome with real guitars and drums played by real people. The result sounds more musical than I thought it would and it reminds me of the pulsing music of US composer Steve Reich. I still hear genes and other viral characteristics within the science data but music wins out in the rehearsal studio.

As a musician, this project has been rewarding but as a scientist, I hope sonifying the coronavirus genome helps people think about its function in new and helpful ways.

I was also challenged to create something almost beautiful out of something so awful. Let’s hope we will soon be able to return to work and live music more “normally”, to the parts of life that engage us intellectually and creatively.

Read more:

Music-making brings us together during the coronavirus pandemic

Mark Temple is a senior lecturer in molecular biology at Western Sydney University and was the drummer for The Hummingbirds.

This piece was originally published at The Conversation.