A new assay for plasma tau proteins brings screening a step closer

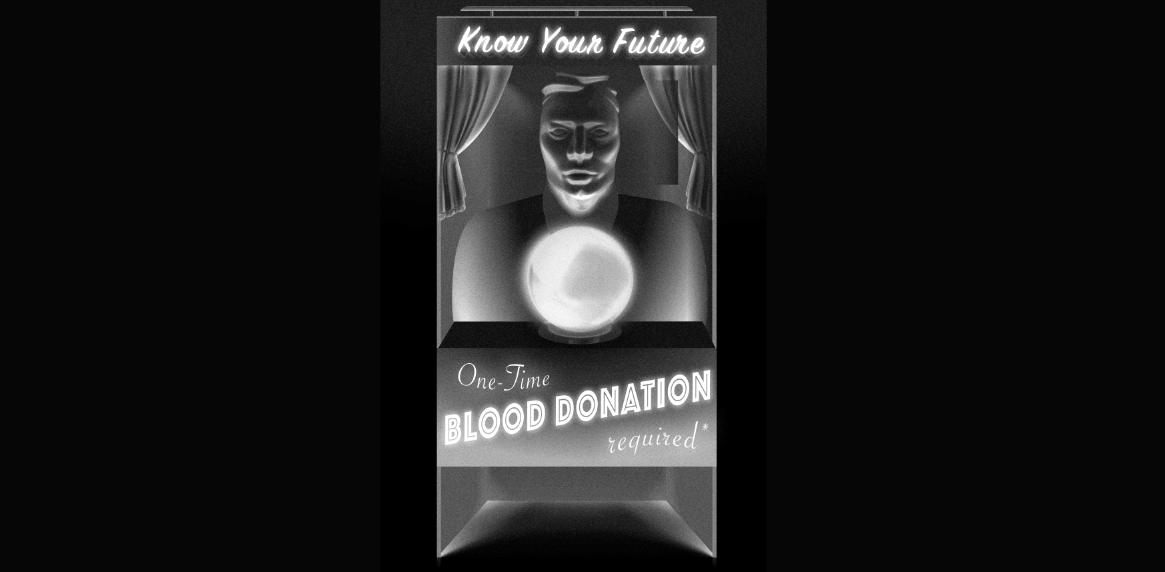

A blood test has been developed that promises to make the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s simpler, and perhaps facilitate large-scale screening.

But so far the diagnostics are outpacing the therapeutics for the most common form of dementia.

An international research effort based in Sweden, and involving the Australian Dementia Network and University of Melbourne, has produced a test for phosphorylated tau proteins (p-tau181) in blood plasma. This hallmark of Alzheimer’s has to date only been detectable using PET scans, lumbar punctures or autopsy.

Published in The Lancet Neurology, the study compares plasma p-tau181 readings of more than 1100 people in several cohorts – young and cognitively unimpaired adults, amyloid beta-positive cognitively unimpaired older adults, those with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) with and without amyloid, and diagnosed Alzheimer’s patients – and finds a “gradual increase” in concentrations along the continuum.

The test provided “high diagnostic accuracy for Alzheimer’s disease [and] predicted cognitive decline and hippocampal atrophy over a period of one year”, the authors write.

“The blood p-tau181 assay has the potential to be incorporated into clinical practice as a rapid screening test to identify or rule out Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology and to guide therapy and clinical management of patients with suspected neurodegenerative disorders.”

University of Melbourne neuropathologist Professor Colin Masters, director of the Mental Health Research Institute, collaborated with the authors and is one of the lead scientists on AIBL (Australian Imaging, Biomarker & Lifestyle Study of Ageing), a longitudinal observational cohort study that is using the test in some subjects.

“One of the biggest advances, if these biomarkers hold up, is we’ll be able to screen large numbers of people in their 50s, 60s and 70s, and actually pin down a true epidemiology of this disease, which we haven’t been able to do yet,” he tells TMR.

“Everyone is interested: is it the environment? Is it genes? So far, nobody’s come up with a very convincing argument that it’s environmental. We can’t really get a handle on this until after we do the proper analytical, epidemiological studies, and that’ll be facilitated by these types of blood tests.”

He says the p-tau181 test would not be used in isolation as it isn’t specific enough for Alzheimer’s, but would be used in conjunction with a recently developed test (not mentioned in the paper) for amyloid-beta, the other hallmark of Alzheimer’s.

“Combining the A-beta42 and the p-tau181, we end up with a test that’s good for individual diagnosis – that is, differentiating Alzheimer’s from other forms of dementia. And also selecting the right people to go into a clinical trial, depending on what age and what degree of cognitive impairment they have.

“If you’re cognitively normal and still positive on this test, we can predict when the onset of the cognitive impairment is going to occur. If you’re amyloid-positive and p-tau-negative, it’s going to be a longer time than if you’re amyloid-positive and p-tau-positive.”

He says a cognitively normal person might want the test if they had a family history, so they could be given early interventions.

“If we know that you’re at risk genetically, then we can monitor your blood changes and then intervene before any detectable biomarker signal exists.

“At the moment, the only interventions we’ve got are these monoclonal antibodies. But in due course, there’ll be other inhibitors of production, the so-called beta secretase inhibitors. We can look forward to a period not long away where we give these things in combination – where we’ve given antibody for a year and then we go on a low-dose inhibition of production of the amyloid using a BACE inhibitor.”

No disease-modifying Alzheimer’s drug exists, despite decades of trials.

But Professor Masters says there are some “very, very encouraging antibodies in development targeting A-beta”, and cites, among others, Biogen’s aducanumab, which is due to be filed for FDA approval later this year after a COVID-19 delay.

He says screening for Alzheimer’s would be no different from screening for breast or prostate cancer, and that “it’s the right of the individual to determine what they know and what they don’t”.

Dr Jenny Doust, a clinical professorial research fellow in public health at the University of Queensland, who has written about Alzheimer’s and overdiagnosis, says the authors’ claims are not entirely supported by their data. First, the data sets show too much overlap in p-tau181 concentrations across the various cohorts.

“You can see in those plots that there’s no level which you could use a cutoff that differentiates people who have disease from people who don’t,” she tells TMR.

Second, the charts of patients one-year progress measured by MMSE (mini-mental status examination) shows a trend of greater decline in patients with more tau – but some with high tau don’t decline and some with low tau do.

“Again, you couldn’t use it clinically because at no level does it differentiate between people who are going to get worse and people who are going to stay the same or even get better.

“There’s an association there, but it’s not a test that you could use clinically to differentiate those people who are going to progress from cognitively unimpaired to MCI or MCI to Alzheimer’s.”

Dr Doust says the lack of perfect correlation between amyloid and tau and clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s makes a pathology test problematic.

“People are fixated on this idea of amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles being the pathology that causes Alzheimer’s, and lots of people have tried to point out that that may be just a by-product of pathology that’s going on, and that that may actually not be the pathology per se,” she says.

“You actually see quite high levels of those things in people who don’t have cognitive impairment as well, so the potential for this kind of testing to lead to overdiagnosis, and also quite a lot of false negatives, is very high.”

Professor Dimity Pond of Newcastle University, an expert on dementia in primary care, says the test seems unlikely to translate into something that a GP could use.

“I think it’s early days, yet,” she says. “Assuming that it actually ends up proving successful, that’s great. However, it’s not going to replace a clinical examination.”

She says people can have elevated tau levels without Alzheimer’s, and cognitive impairment can have transient causes – such as a cold, infection or general anaesthesia – making the diagnosis tricky even with a pathology test.

An Alzheimer’s diagnosis can trigger changes in a person’s life, such as activating power of attorney, having finances redistributed or being put in residential care.

“GPs do get criticised a lot for delaying making a diagnosis of dementia, but it [such a diagnosis] is not without its harms. If you can’t 100% rely on a test – and we can’t 100% rely on this test – then we’re still going to have to use our judgment about it.

“You have to look at the whole person, which is what GPs are good at doing.”

As for large-scale screening, the WHO’s criteria stipulate that there must be an accepted treatment.

“It’s not really treatable – it’s a question of management: gradual, sensitive implementation of support strategies that keep the person as independent as possible without endangering them or other people,” Professor Pond says.

“Because we don’t have a pill. You can always find someone who says there’s one happening next year, and maybe there is. But I’ve heard that every year for the past 20 years.”

She says, however, that practitioners must engage with the difficult question of cognitive impairment and recognise the need to broach the topic with a patient – “and at some point it might be that they really want to know. And that would be the time to do the blood test.

“I certainly went through a stage of thinking I wouldn’t want to know. But at this point – I’m in my 60s – I think I would want to know, because there’s things I would like to do.”