A significant piece of research touting that the after-hours providers are rorting the system looks like it’s flawed

Research published in the peer-reviewed Australian GP journal, Australian Family Physician this month, and then in the widely distributed online academic site, The Conversation, and which has been quoted widely now in the media as providing a strong indication that after-hours has no effect on emergency department (ED) presentations, is almost certainly flawed, and therefore misleading the public and policy makers.

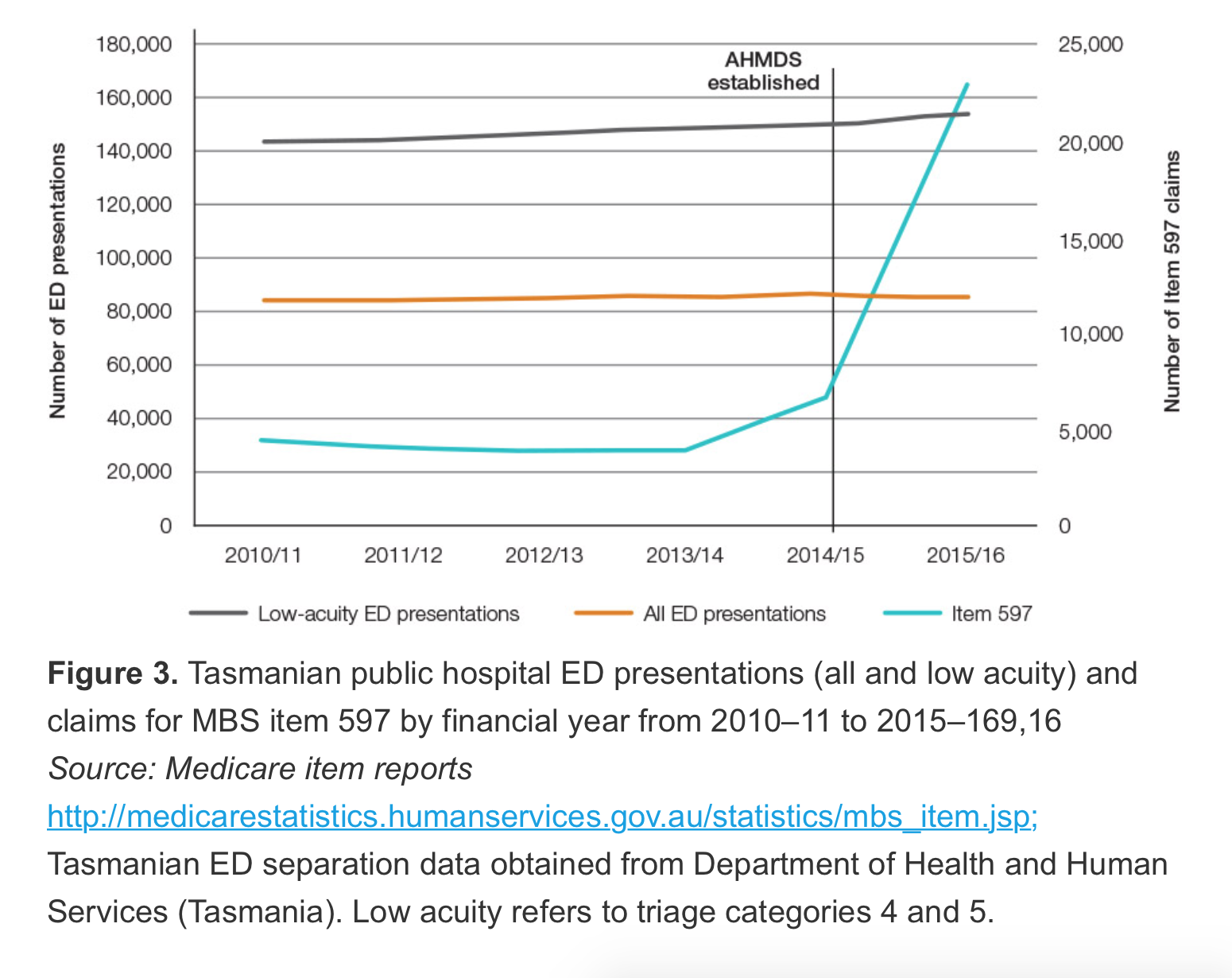

The research piece titled Up up and away: The growth of after-hours MBS claims, is a before and after desk research piece which uses ED data averaged over 24 hours from Tasmanian EDs as a baseline to see if there has been any decline in presentations as after-hours services have grown substantively in that state. The authors found presentations stayed stable for all presentations, and actually increased a little for low acuity presentations (see table below).

At the same time, the authors map a huge increase in urgent after-hours item number 597 in the state since 2013-14. Their conclusion is that the increased provision of after-hours consultations does nothing to reduce ED presentations.

In The Conversation article about the research the authors say in opening the article that “rather than reducing the need to visit the emergency department, their rise in popularity has been accompanied by a slight increase in visits … our findings … question whether these convenient house calls are really the best use of taxpayers money”.

But the research appears to have a fatal flaw. After hours operates “after hours”, from 6pm to 8am, with the peak period for calls being after 9pm when access to clinics which operate at night tend to close. This research compares an average of 24 hours of presentations, and in Tasmania only. And it’s data on 597 item billing stops in mid 2016, when data is available from the MBS for this data until the end of the first quarter of this year. If the data is adjusted to only “after hours”, and is updated until the first quarter of this year, it tells an almost opposite story to this research.

Data for ED presentations by hour of the day is available from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. From 2011-12 to 2015-16 It reveals that across Australia in the following after-hours timeframes the presentations to ED decreased as follows:

- From 6pm to 8am: by 0.7%

- From 7pm to 8am: by 4.7%

- From 9pm to 8am: by 7.3%

In hours, between 8am and 6pm ED presentations grew by a whopping 5.5%. And the 24 hour average is 3.4%.

The Medical Republic is not drawing a conclusion that this is proof that after hours is working. We aren’t economists or statisticians, and there are no peices of controlled research which can confidently make that link that we are aware of. We do think, however, that it says a lot about the how the after-hours debate is being run on, at times, inaccurate, and ‘convenient’ , data, potentially to suit political purposes.

We aren’t suggesting, either, that the authors are being sensationalist. However, their research and their article in the Conversation has been reproduced with authority by several major metropolitan newspapers as evidence of why the MBS review is moving to close down the use of urgent items by after-hours providers, and a reason why, potentially, after-hours providers are rorting the system. Unfortunately, the actual data looks like it might be suggesting that after hours is working (ie, it is reducing ED presentations). But no one has done that research properly. Why not?

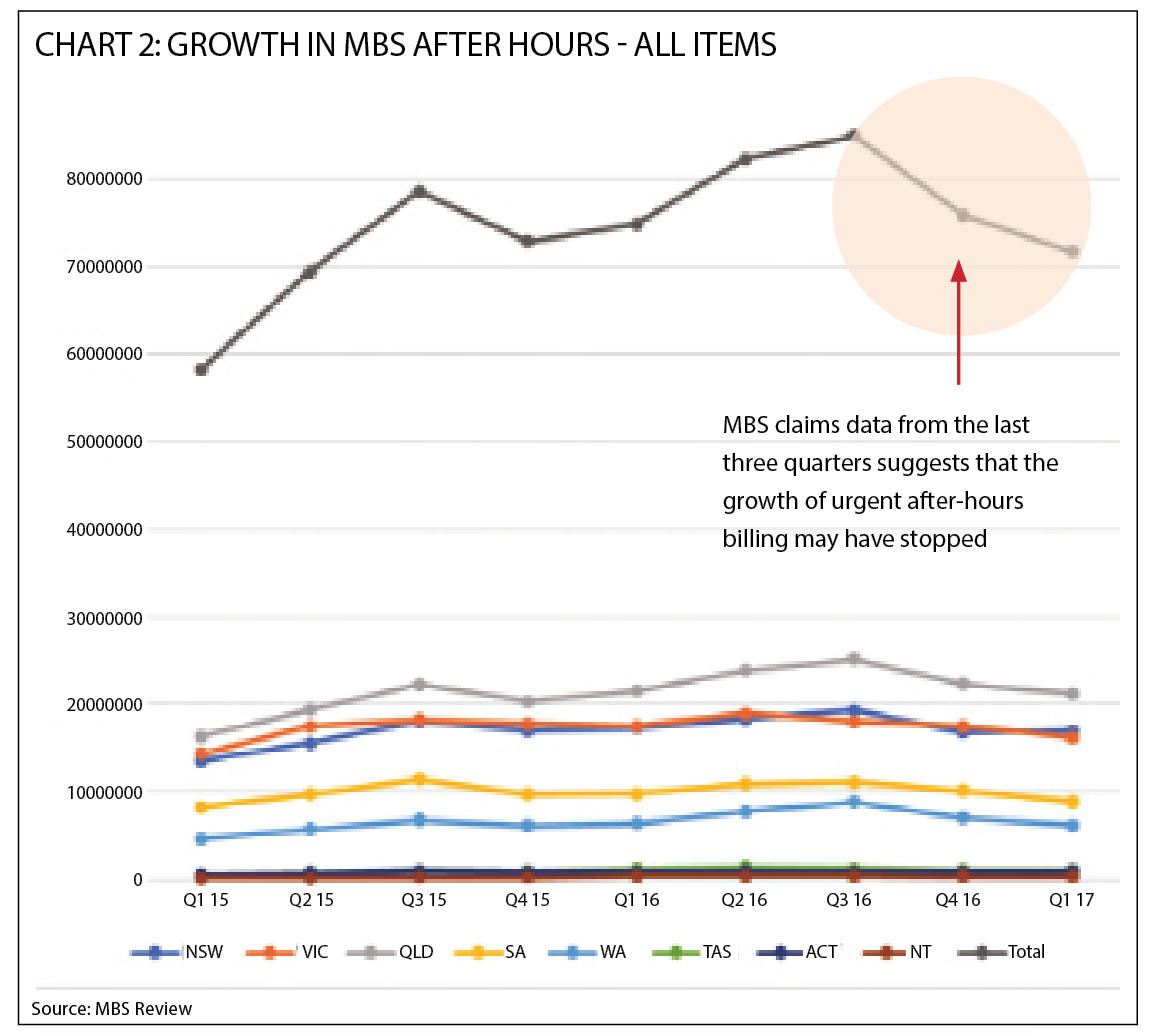

Further to this problem with this research article, updated MBS item data suggests that in the last three quarters, the growth of the use of urgent items by the after-hours providers has almost come to a complete stop. The Australian Family Physician research however indicates, using different scales, that the use of these items is explosive and not stopping. Again, the research paper is showing something which is not an accurate reflection of what is going on, this time by not having up-to-date data. The chart below shows all MBS after hours items claims by quarter since the beginning of 2015. The last three quarters have been going backwards at quite a rate.

Again, the reason(s) for this sudden stop in growth is unclear. The problem is, no-one is even speculating as to what could be happening. We are just making assertions as to what is occuring.

After-hours providers contacted by TMR say that their growth into new areas created by geographical expansion and public-awareness campaigns has reached a natural limit and the data is reflecting this stop in growth.

Others have speculated that the sudden stop is a result of the after-hours providers rapidly pulling back promotion in their service areas in response to the controversy surrounding their growth and an attempt to prevent what has now occured, government intervention. The after-hours providers denied this when it was put to them.

TMR contacted the researchers of the Australian Family Physician article for comment and they confirmed that they had not compared after-hours ED presentations with the hours these services actually operate in, and that they had not had access to the most recent three quarters of data on item growth. However, they did point out that, while not actually growing, ED presentations in the full after-hours operational time period of 6pm to 8am, had virtually stayed steady. They would not comment when asked “did they compare the amount of after hours visits by time and whether most of those visits occurred after 9pm anyway”?

They also pointed out that this was only a “before and after” piece of desk research and therefore it would suffer from some methodology issues, as it was not a specifically designed piece of research. When asked whether they felt the government should fund someone to do specific research to understand the issue better, they said “yes”. Asked how much such research might cost, they suggested between $50,000 and $100,000.

Despite acknowledging potential flaws in the methodology, one of the authors did remain adamant that the after-hours providers were “rorting” the system.

“It’s just not possible to have that growth in urgent items. The clinical need isn’t there,”, author Dr Mark Nelson of University of Tasmania, told TMR.