Most people own items they will never use, but what happens when patients start to drown in their own possessions?

Rotting couches, soaked from the rain and piled high with collapsing boxes of soft toys, winter coats and flyers from the local takeaway, sit forlornly on the nature strip.

Look closely and you might be able to piece together a narrative of someone’s life. The pink bikes with training wheels must mean they have daughters; the abandoned ski equipment harkens of unfulfilled winter-fitness dreams.

Since last Christmas, the charity St Vincent De Paul reports a near 40% increase in donations around the country.

What is going on?

Australians, at least in the main urban centres, seem to be decluttering their homes in an unprecedented fashion.

But could this wave of consumer minimalism by folk who previously had an exploding shoe collection or a Bunnings tool addiction, indicate less about their cleaning prowess and more about their Netflix history?

Tidying up with Marie Kondo was the trending Netflix series over the TV silly season, and it’s now one of the most popular series on the digital streaming service. In the first season, Japanese “organising consultant” Marie Kondo is invited into American homes by people who want less clutter in their lives.

Kondo “frees people from the trappings of materialism” by asking them to hold each possession and ask themselves whether it “sparks joy”. If the item no longer charms and delights them, that’s a sign it should be discarded.

With polite tone and welcoming smile, Kondo brings her clients the good news that they no longer have to live in between shelves of books they’ve never read and piles of once-loved clothing. Even the clothing that is retained, is subjected to the “KonMari method” of folding and compartmentalising belongings.

The overwhelming message implied throughout the entire series is that through decluttering, discarding the unnecessary and organising everything else, people will regain control of their lives and find true happiness.

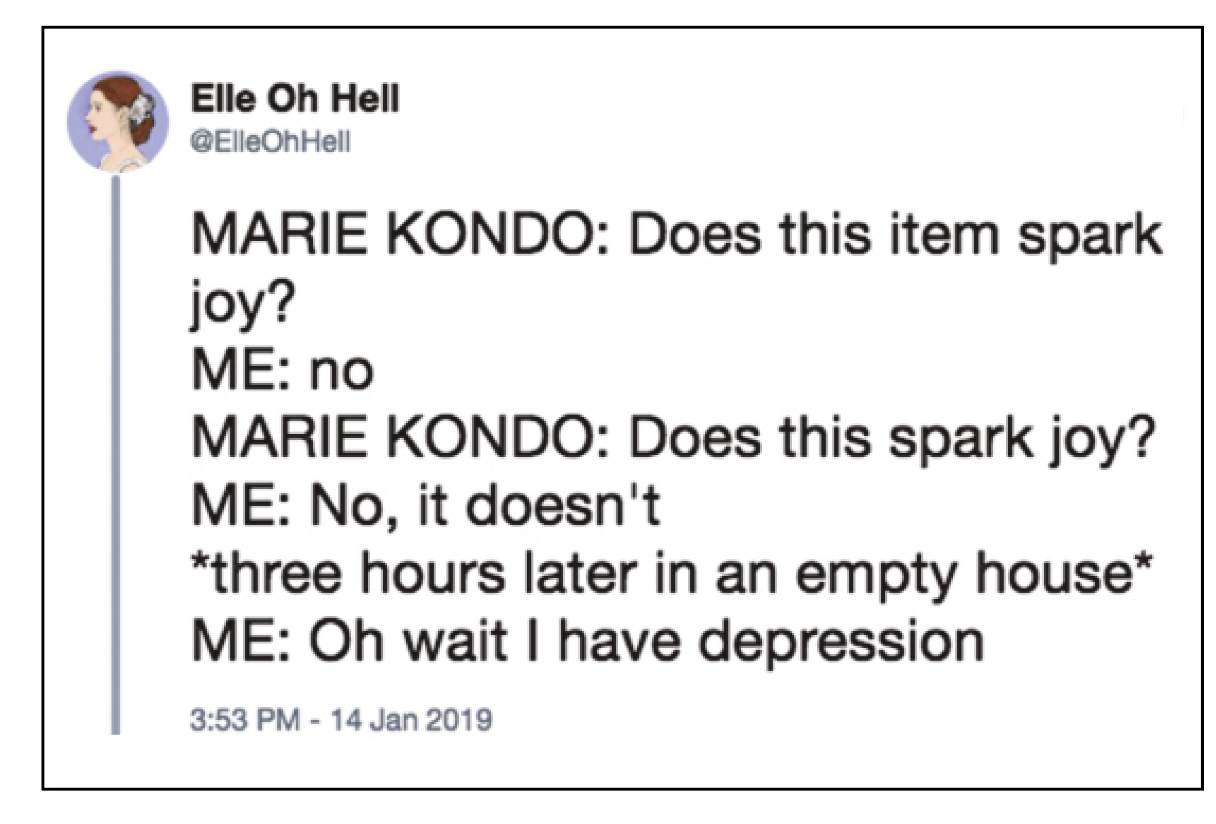

Kondo’s influence has spread wide and far, with memes and counter-memes raging across the internet. Social media seems to have become an “I’m tidier than you” playground challenge with the protagonists boasting of their KonMari triumphs.

There is little doubt this current trend is proving to be a boon for the cleaning industry, the skip bin renters and recyclers but how is it faring as a means to psychological well-being? Can our decluttering frenzy and exquisitely arranged T-shirt drawers really fulfil the implied promise of happiness and serenity?

Well, according to psychologists, there is currently no evidence that clinicians should be encouraging the KonMari method to patients despite its growing popularity. The reality is, as you might expect – the equation that says lack of mess equals happiness is a tad simplistic.

For example, while the focus of Kondo’s series is discerning what items “spark joy”, Professor David Castle, a psychiatrist at St Vincent’s health Melbourne, says it is important to analyse what joy means to each individual.

“When you ask, ‘does this bring you joy’ some people think joy has to be laughter and happiness and that sort of overt emotional response, and for other people, it’s a different sort of joy,” he says.

“Some things you want to hold onto even if it evokes sad memories. Sad memories are arguably important memories to hold onto and to cherish in some ways because they are part of what one’s life has been, and they are part of what one needs to integrate with their psychic journey.”

“I’ve had some patients which hold onto things because they bring them, not so much joy, but what we’d call solace,” he says.

Professor Castle shared a story of a woman who was adopted as a baby and had gone on to find her birth mother when she was in her 30s. After establishing a close relationship to her birth mother, she was heart-broken when she died. She started collecting soft toys and soon her whole house became full of them. They were symbolic of the warm and caring attachment object she lacked in childhood, discovered when she found her birthmother, and lost again when her birthmother died. “She could not bring herself to throw away these things because of the symbolic value,” says Professor Castle.

For this woman and many like her, clearing away possessions, even if they don’t serve a useful purpose or even if they do constitute “clutter” may in fact cause psychological harm.

As a therapeutic tool, the KonMari method is certainly not a one-size-fits-all solution.

But as the trend to tidy continues to gain momentum – it does seem to be proving something of a diagnostic indicator.

As you might suspect, a person’s reaction Kondo’s message, be it religious adoption or, at the other end of the spectrum, distressed rejection might actually be indicative of a more serious psychological condition.

Urge to constantly tidy

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) affects nearly 2% of Australians. For these patients, a compulsion to tidy and compartmentalise their lives is not a choice but a debilitating condition.

While Kondo demonstrates the serenity that comes with order, some people might be crippled by anxiety if they don’t have everything in a certain place all the time. (If the books on the shelf aren’t in alphabetical order, it might be hard to concentrate on anything else…)

The OCD patient does not find pleasure in these behaviours but performs each ritual to prevent an objectively unlikely event and calm the anxiety that is associated with the anticipation of this event.

While there has been no suggestion the series is causing OCD, one active reddit thread has users with OCD discussing how their symptoms flare up as they practise the KonMari method. This suggests people are recognising their disease through the show and may be encouraged to seek treatment.

This should be seen as a plus, as patients with OCD are notoriously reluctant to ask for help.

“The very act of consulting a doctor can be anxiety provoking or potentially stigmatising for people when they are unwell. It can be challenging to detect the more intrusive symptoms experienced by those with true OCD,” says Victorian GP Dr Caroline Johnson.

Management and treatment can be challenging and complex.

“For a patient with OCD we recommend avoiding a rushed referral process,” she said in a paper co-authored with psychiatrist Dr Scott Blair-West. For these patients, consistency in care is crucial, as anxiety might be heightened if they are referred to a second, or third therapist so it is imperative that from the outset, patients be directed to services that have the specific expertise necessary to treat this condition.

Holding on for dear life

And while the KonMari method must seem like a perverse endorsement of their illness for someone with OCD, one can only imagine what the sight of all those skip bins and recycling bags is doing to those poor people for whom discarding possessions is a major cause of distress.

Hoarding was once considered a symptom of obsessive compulsive disorder, until 2013 when “hoarding disorder” was added to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Hoarding is not the same as collecting. People who collect usually experience tremendous satisfaction when acquiring additional items or reviewing their collection and will commonly be keen to discuss their passion. In contrast, people with hoarding disorder experience feelings of shame, guilt and embarrassment and will often go to great lengths to conceal their condition – deterring visitors and avoiding discussing the issue.

Why these people acquire items, and why they struggle to throw them away is the basis of this psychological disorder, says Associate Professor Melissa Norberg from the department of psychology at Macquarie University in Sydney.

In general people acquire items because they are functional and/or they bring pleasure.

“We don’t just buy a shirt because it just covers our body, we buy it because there’s something about it that we like,” Professor Norberg says.

It’s part of human nature to get emotionally attached to the things we own. But for most of us this attachment isn’t particularly strong. We have the ability to turf out items that are no longer useful from time to time, although it might harder to discard those items with a sentimental value.

The DSM-5 criteria states that people with hoarding disorder apply a disproportionate value to an item, which drives an emotional connection to it.

Recent research published in the Journal of Behavioural Addictions shows people who attribute more feelings to inanimate objects have higher acquisition tendencies.

The study included more than 300 patients with varying levels of acquisition problems. Along with a difficulty to discard items, people with hoarding disorder also struggle with resisting the urge to acquire more items, whether through buying or free procurement.

The participants were asked to self-report their acquisition tendencies by responding to questions on a seven-point scale. Do you feel compelled to take free items in general? The responses varied from one, not at all, to seven, very much. Higher scores indicated a higher level of acquisition. The distress the participants felt was measured in the same fashion where people responded to prompts about their level of discomfort, on a five-point scale, zero being very little and four being very much.

If the participants were intolerant to distress, they were likely to be more attached to their acquired objects, the authors found.

Kondo’s instruction to “thank” an object for serving its purpose before discarding it, does appear to recognise an emotional connection.

While some could argue the gesture helps people focus on the utility of objects and the fact that that utility no longer exists, Professor Norberg is concerned that it promotes anthropomorphism, where a person projects human qualities onto an object.

Kondo makes it seem like unneeded items can be relinquished in a week.

But, for patients with hoarding disorder, this is unrealistic and potentially counterproductive. Even without the thank you, judging whether an item should be kept on the basis of current need is unlikely to work in patients with this condition. “Often, people with hoarding disorder will say, ‘I might need it. It might be useful to me in the future’, so this psychological attachment enhances that perceived usability,” Professor Norberg says.

Health implications

Hoarding disorder is now a well-recognised psychiatric condition with its own distinctive DSM diagnostic criteria. And, in addition to the significant psychological morbidity, the illness is associated with many other physical health risks.

Patients with chronic hoarding disorder, often live in conditions that are unhealthy, unsafe and unsanitary.

“For people with clinical hoarding it can get to a point where they’ve got stacks of clothes, books, papers, knick-knacks, electrical items and all sorts of things stacked up to the ceiling,” says Dr Imogen Rehm (PhD), a clinical psychologist and lecturer at RMIT University.

As the hoarding becomes severe, the patient living quarters tend to become more and more restricted. The excess of acquired objects increases the risk of falls and injuries, especially among the elderly. Infestation with insects and vermin is commonly found in the homes of people with hoarding disorder.

Access to cooking and laundry facilities will become increasing limited, and even sanitation and bathroom access can be affected with major implications for health.

When hoarding disorder reaches this stage, it can also pose a serious fire risk. Fire crews in Victoria report they attend a hoarding-related incident once a week.

In addition to the crowded living quarters posing a hazard, fire crews often have difficulty accessing the premises.

Severing emotional ties

Hoarding disorders can be difficult to diagnose in primary health care, says Simone Isemann, a clinical psychologist facilitating the Hoarding Treatment Group for Lifeline Harbour to Hawkesbury in NSW.

“Generally, there is quite a lot of shame around hoarding disorder, so people aren’t necessarily presenting, ‘Look I have a real problem. My home is really cluttered and full of stuff’,” she says.

Often when patients present to a physician for treatment, the hoarding disorder is already chronic meaning the patient has been gathering items for 20 or more years. In other words, people usually present late.

This was confirmed in one study that found hoarding disorder was three times more common in people aged over 54 than in people aged 34 to 44. Symptoms of the disorder often develop during childhood but become clinically significant during middle age, the study says.

Sometimes a GP may suspect a patient has a hoarding disorder. Half of patients with this condition will have co-morbid depression. Affected patients may appear dishevelled, carry lots of bags, be disorganised and frequently lose or misplace scripts or paperwork.

Often the true extent of the severity of the condition can be apparent when visiting the patient’s home, but as GP home visits are now becoming less common and the patient’s general reluctance to have anybody come to their home this is less likely to occur.

If a GP suspects hoarding may be an issue, Ms Isemann suggests asking the patient directly as a first step. GPs can ask the question “Do you ever find it difficult to let go of your possessions?” or “Is clutter in your home creating a problem for you?” “If the person acknowledges that, then see if they are willing to talk to a psychologist,” Ms Isemann says.

The Lifeline program Ms Isemann facilitates emphasises education and motivates patients with hoarding disorder to start discarding possessions through a 15-week program.

“This type of major behaviour change works really well in a group setting because there is a huge amount of normalising,” Ms Isemann says.

“It gives them hope when they realise they aren’t the only people who think and feel the way that they do, and when others make changes it can be very motivating for other members of the group,” she says.

Cognitive behaviour therapy is recognised as the most effective treatment for hoarding disorder. As most patients are older than 50, the decluttering process after years of acquiring can take months or years to complete. These patients often need home sessions where professionals come to their house to assist in the clean-up process both psychologically and physically.

Shows such as Kondo’s are unlikely to help people with hoarding disorder. The quest for tidiness and lack of clutter tends to demonise those people who cannot live without mess and “stuff”. They add to the stigma associated with this disorder.

According to psychologists, patients with hoarding issues who watch shows such as Kondo’s often question whether they will be supported in the way they need, if they seek treatment. For people with hoarding disorder, Kondo sorting through their belongings would not be therapeutic, but anxiety inducing. There is no recognition of the distress discarding these items would cause.

“We know of several cases in which hoarders have committed suicide following a forced cleanout,” writes Randy Frost and Gail Steketee in their book Stuff: Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things.

The evidence suggests treatment of hoarding disorder needs to focus on two key elements of the condition. Firstly, the abnormal emotional attachment to the acquired items needs to be addressed and secondly the patient needs to be taught how to tolerate distress.

And while that might sound straightforward, all the experts agree treating this condition, especially given how chronic it usually is, is not easy. It will certainly take much longer than a Netflix series.

Judging by its popularity, Kondo’s show, and perhaps more importantly her message, has obviously answered a need in today’s society.

One can’t help but think reducing our level consumerism and streamlining our life can only be a good thing, with a few exceptions, of course.

But as we sit in our now decluttered and organised homes, what will be the effect of this philosophy on our collective psyche?

Will our lives “spark joy” or do we really “love mess”?