But then again, without the technology, it wouldn’t be possible. Now GPs just have to get on board and when that happens the funding will follow. Won’t it, Mr Hunt?

Technology might be starting to become a fall guy for why the introduction of integrated care models isn’t going much faster, as it should. As usual, it’s much more complex and people issues are at the centre of that complexity

Somewhat ironically, in almost all successful cases of digital transformation, “it’s not the technology, stupid”, eventually becomes a catchcry for those leading the change.

When transformation is really in play, most often the technology has been the catalyst of the shift, despite naysayers being quick to paint it as the culprit when initiatives are slow in being adopted.

The main barriers to change in nearly all cases involve issues of people: awareness, culture, incumbent politics, legacy model protection, and probably most importantly, leadership.

And leadership comes from the most unexpected of places at times.

In the case of newly emerging models of patient-centred care, or integrated care models as most GPs would see them, and its major government incarnation, the Health Care Homes (HCH) initiative, all the classic elements of such change are playing out. The technology, though certainly not perfect, is there, and not hard to implement.

Two leading chronic care management solution providers – Precedence Healthcare with CDMnet and MediTracker, and Ocean Health with Linked EHR – are out there today but struggling, amid all the issues that tend to blur transformational change, to gain the right level of awareness among doctors and regulators (more on that later).

The will on the part of most GPs, especially from a job satisfaction perspective is there, mostly. And we are seeing leadership on this change springing up everywhere. From the big corporates, whose initial embrace of HCH should signal to the rest of us that this change is almost definitely coming, to the smallest of practices, and even sole practitioners, who are adopting the HCH model.

That single-doctor practices are involved and making progress is probably the clearest signal that this isn’t a technology problem anymore. You do not need to have the backing of a corporate to afford to move to much more effective chronic care patient management. You need something else.

Many GPs are interested in moving to these newer patient-centred models, but are understandably cautious as they represent a major departure from their traditional and proven business model, namely fee for service. HCH is a complex funding proposition, even if it is funded properly, which it currently isn’t.

So there is a very real tri-fecta of the unknown for GPs in moving to integrated care: technology, regulation, uncertainty of income into the future.

The latter two issues are created mainly by the government, whose wavering position around supporting HCH properly has reverberated throughout the community and been communicated largely as, “We aren’t entirely sure we will end up funding patient-centred care properly therefore everyone be on guard”. To which you might add, “And you can’t really trust us anyway, as we’re the ones who thought it was a cool idea to freeze your pay for the last three years”.

This is all classic, early transformation-stage disruption. The technology is here, the willingness of the workforce (GPs) is mostly there, and there is little likelihood the government will not end up moving the funding base of GPs significantly towards integrated care models.

It has to. And it knows it has to.

They (those in the government) are just being their usual bureaucratic, rear-end-covering selves, and as a result we are witnessing them move on this most important of changes to our system at glacial speed.

How does one put a rocket under this thing? Most everyone one wants it. The precursors are all in place. It is that important.

One thing. We can’t wait for the government. It’s not their fault. They mean well and they are trying. But government, especially the federal government, is quite dysfunctional these days, and almost no matter how good the people are in there, and there are lots of good people, the systems, politics and processes are going to keep things slow.

If you don’t believe that assessment, read the latest Productivity Commission Report where the government marks themselves quite plainly as dysfunctional and a hinderance to productivity. You can see it here: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/productivity-review/report. Go to the healthcare chapter and you’ll see that they know that patient-centred care is the future of everything, including the funding of GPs for outcomes rather than turnover.

“The international and Australian experiences with integrated care indicate that, if properly implemented, it leads to gains in health outcomes for patients, improvements in the patient experience of care, reductions in costs, and improved job satisfaction for clinicians,” the commission says. That couldn’t be much clearer.

So the government will be there. We just need to get them there faster than they can do it themselves somehow.

How?

Digital transformation almost always drags government with it if the market message is strong enough and the market is moving ahead at a rapid-enough rate. It sends them priority signals and their good people kick in and they are forced into catching up.

But we still have some chicken and egg here. I’m not sure the technology works, and I’m not sure if I get it working, I will get paid properly. What is my next move?

GPs need assurance that moving to HCH or other patient-centred care models won’t mire them in technology issues and won’t adversely affect their already strained income stream and work life.

Transformation events almost always start with people breaking out and taking a lead that creates awareness among all the others. That’s the leadership part.

The corporates – IPN and Primary – both have very large trials running with HCH and both have leadership that is strong and GP-led. That leadership is Dr Ged Foley in IPN, and now Dr Malcolm Parmenter, who has just started his stint at Primary after a long run successfully building the IPN brand.

If they succeed, that will be some marker. Remember, it’s in their interests to succeed here if they want to attract good quality GPs to their business, which they both want to do.

These corporates don’t invest like this lightly. They know the change is coming. It’s a smoke-signal we can trust.

But not every GP is going to trust a corporate smoke signal. Certainly not those who sit around an chat around mythical horror stories (and some not so mythical) about working at Primary.

Corporate medicine unfortunately still, to some degree, carries a stigma for many doctors – largely created by the past behaviour of Primary , but a few of the boutiques as well. The “corporate GP medicine brand”, even that of IPN, which pursued much higher ground than Primary in the past brand-wise, has a fair bit of work to be done it.

But some GPs see that navigating such massive change is better done within the bowels of a big, well-rigged ship. If a corporate does go belly up, which is not likely, or its just not the life they want, they are mostly more flexible these days so a GP can always take to the lifeboat and start rowing again in the open ocean.

Many non-corporate GPs would necessarily identify with initiatives taken by corporates as examples of how they should develop their business, or the business of general practice all up.

In the end, the past misdemeanours of corporates has created a trust issue that still lingers, doctors Foley and Parmenter notwithstanding. That, and the fact that corporates only account for about 20% of our overall general practices, probably suggests that the real breakout is going to come from some of the small practices with some very determined and smart doctors.

Some of these principles of smaller practices, who are successfully moving to longitudianl and integrated care already, are showing a brand of entrepreneurial leadership that you see in classic cases of digital disruption.

They have an attitude, they’re determined, they want the future to be great, and they’ve made themselves understand and apply the technology. And they are going for it.

They are paving the way for others, proving out the case for GPs that it will be worth the risk.

In the parlance of the classic business pop text, The Tipping Point, they are our “mavens”.

Before you decide you’re a “maven”, or go rushing off to become one, it’s not for everyone. Mavens come from the village of the curious, engineer-like, builders, who are calculated risk takers, and who are all about ideas and doing things better. And communicating. Which is where things start to really change. They are also stoic and have endurance. They are good at getting back up after failing. And the learn from it.

Hang on. Are small practices really on top of the sort of connected technology we are talking about here? I thought you needed an army of IT people, geeks and money to get on top of that stuff?

No, you don’t, and yes, some small and single-doctor practices are breaking out as this peice is being written.

According to Precedence Health’s CEO and founder, Professor Michael Georgeff, some of the most-effective implementations of the CDMnet and Meditracker systems is in small and single-doctor practices.

Precedence systems are also being used by the corporates. Precedence is owned by Sonic, which owns IPN.

But Professor Georgeff is trying to make a point, which is that “it’s not the technology [stupid]”, holding this back now. It’s GP reluctance. However, he very much understands the GPs’ concerns.

“At the moment managing chronically ill patients is a huge challenge because the evidence pointing to longitudinally planned care with a care team and GPs is just being overloaded in managing this in their current set-ups,” he says.

It’s a major and complex undertaking if you haven’t got the technology in place and you have to manually do the paperwork and scheduling of all your patients appointments and follow ups with all the providers involved.”

Not surprisingly, today, more than 80% of care plans remain languishing in GP filing cabinets, with patients, allied healthcare professionals, or the GP themselves buried too deeply in other work to follow up – all largely because there is no ability to co-ordinate, remind and alert follow up, and share information seamlessly between all the parties involved. This is what the new technology does for a GP.

Professor Georgeff admits that there is still confusion in the market around the technology.

“It is confusing, but it should not be,” he told The Medical Republic.

“There are not many technologies for connecting GPs and the care team, and the patient. There are even fewer that provide real digital care plans that help handle co-morbidities and automate follow up and review (the big costly things in the HCH).”

A recent matrix of available technologies produced by the South Eastern Melbourne PHN, designed to lower the confusion for practices, confirms what Professor Georgeff is saying. In fact, this matrix created controversy among the various software vendors because it initially ranked the software available and used as its benchmark the Precedence CMDnet product, giving it a rating of 100%, against which all others were measured.

The next product available, that does largely what CMDnet does, is Linked EHR at a 70% ranking, a joint venture between a NSW-based PHN and Ocean Health Systems, and after that the next product, Extensia, is rated at 50%.

The Medical Software Industry Association, (MSIA) for obvious reasons, wasn’t very happy with this ranking system.

The ranked matrix says essentially, that GPs really only have two products to choose from at this stage. Which, it is correct, at least means that choice is not going to be a big issue, for now anyway. The emerging metrics on the chronic health management market make one suspect there will soon be others.

Notably the controversy on the SE Melbourne PHN matrix caused it to re-issue its matrix sans the rankings. You can access that tool at http://www.hchwiki.com.au/Care_planning. The MSIA matrix is available here: http://www.msia.com.au/healthcare-homes/

Prof Georgeff’s advice is to get your PHN to help. He says of the MSIA matrix, “it would be very hard for a GP practice to understand how to differentiate these products [using this matrix] without quite deep knowledge”.

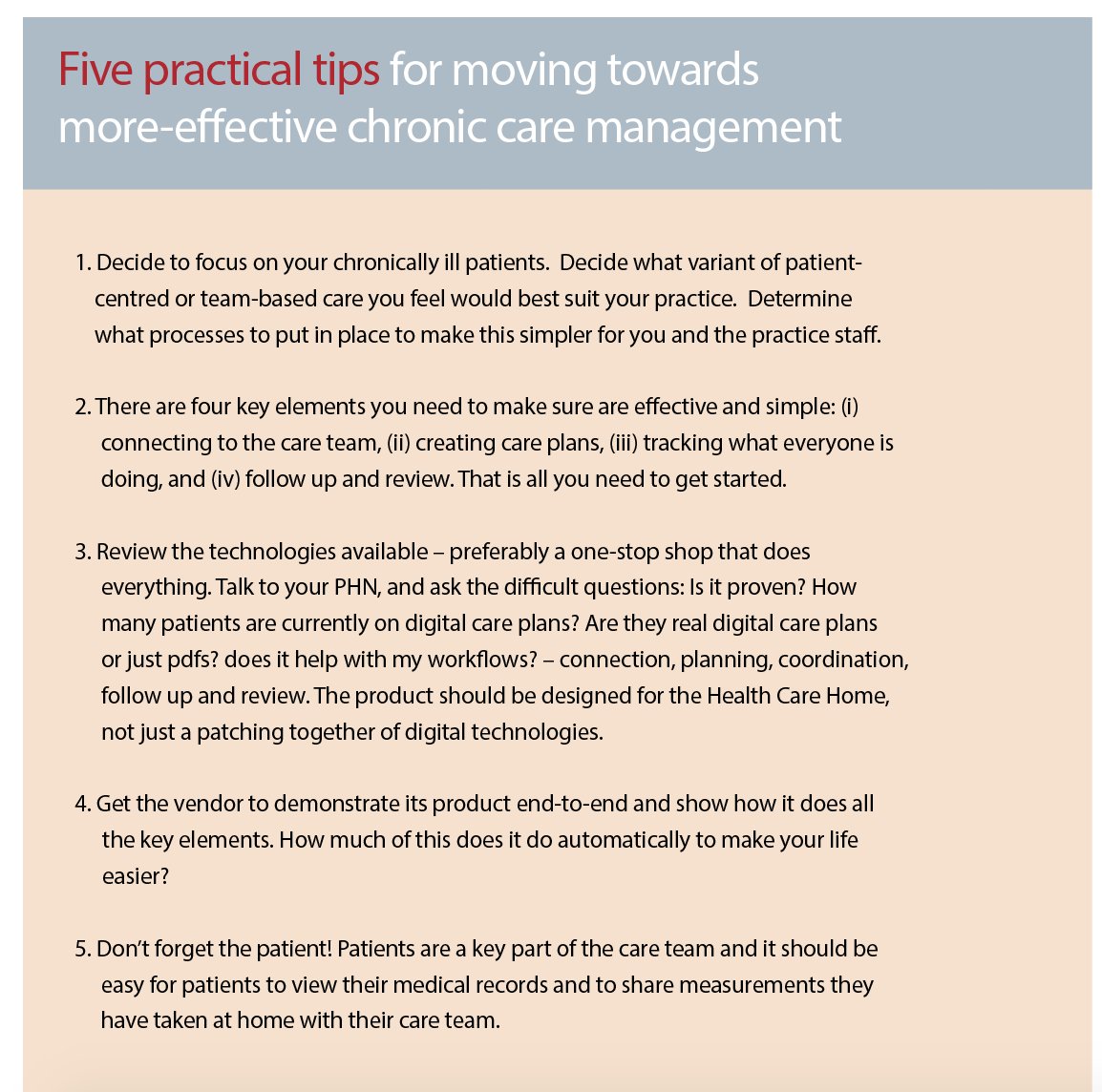

If you’re wondering where you even start in this huge paradigm shift for the GP profession, Prof Georgeff, is very clear on a starting point.

“If you’re starting on this journey begin by forgetting about technology,” he advises.

“Your very first step is to understand and decide to commit to the idea of the patient- centred model or the concepts surrounding longitudinal patient care.”

Once you’re on this path, he says there are only four things you really need to think about:

• I need to connect to the care team to be able to share information easily

• I need to be able to create care plans easily

• I need a simple way to be able to follow up on these plans

• I need to be able to co-ordinate with the care team seamlessly along the way

Prof Georgeff has provided a further five starting points in the table above.

Are we near a tipping point for this paradigm shift, given all the elements we have lining up?

Prof Georgeff thinks we are very close and for that reason most practices, corporate or otherwise, should be active in starting to at least understand the context of how they operate and how they will manage the shift.

There are still issues.

The HCH trials are painfully slow. The government is painfully non-committal to the HCH funding. The RACGP remains opposed to HCH because the government is not putting enough money in to make it work, which is a good point.

Interoperability remains a hold up, particularly because commercial concerns, particularly the path providers are holding onto their data and old business models rather than embrace the connected world, like most other markets are, where connectedness means growth.

But all the signs are there that these obstacles can be broken down quite quickly by a few smart and high-profile mavens leading the way.

Or maybe even one of the corporates, although somewhat ironically, their medical practice divisions are being held back by their pathology divisions, which are the worst offenders in blocking the opening up of healthcare interoperability.

One things is for sure, it’s not a technology issue anymore.

It’s a people issue.