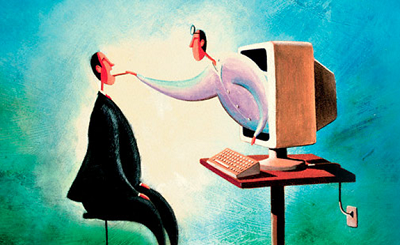

Restrictions on eligibility for telehealth started off too tight, but now they have swung too far the other way

Relaxed rules around Medicare rebates are encouraging a telehealth-only business model that GPs fear will degrade care in the short and long term.

The numerous businesses now advertising bulk-billing services include new ones and those that were only billing privately until the COVID-19 MBS telehealth expansion. Appointment engines have also begun integrating digital consultations, with one touting its service as “the Airbnb of telehealth”.

The “call centre” model is light on overheads, favours convenience over quality and may not offer long-term accountability or data security, AMA NSW president Dr Kean-Seng Lim told TMR.

“They’re not setting themselves up to care for patients on a continuing basis, so there’s very little accountability,” Dr Lim said. “They can push all the more complicated conditions back to usual general practices, and in fact make things worse for healthcare overall by fragmenting care.”

Dr Lim, a GP, said while the item numbers had originally been only for patients who had been to a practitioner – later changed to practice – in the past year, that had been quietly removed.

“There was an understanding that these numbers were to be used by existing practices as opposed to new telehealth-only providers,” he said. “Somewhere along the way, those elements have been lost.”

He said the six pillars of quality primary care were patient-centeredness, accessibility, comprehensiveness, continuity, coordination of care and accountability. Telehealth-only services focused only on accessibility.

“It’s a bit like junk food – it’s quick and easy, but it’s not necessarily good for you.”

Dr Lim said the standards around software also appeared to have been “watered down”, meaning patient data could potentially be hosted in jurisdictions with laxer security. Continuous health records were also unlikely to be maintained.

“There are so many ways this starts to go wrong when you really drill down into it,” he said.

TMR has also heard from patients using the platforms who have experienced a lack of clarity around who they are speaking to, where their data is going and who is paying.

One patient, an Australian health executive, said he had used the Medinet platform (which pre-dates COVID-19) to get a repeat statin prescription. He provided his Medicare number and was told he’d be connected to a doctor, assuming it would be via video or telephone.

Instead a text chat was initiated. He was asked the drug and dosage and whether he’d experienced a few common side effects, then the prescription appeared and he was invited to “check out” – it was over within three minutes.

The chat was so brief, perfunctory and basic it might as well have been a bot, he told TMR.

When asked, a Medinet employee told him he’d been bulk-billed, even though the MBS item numbers are only for videoconferencing and telephone calls.

But Medinet CEO Tess van der Rijt told TMR that all billing decisions were up to the doctor, who might choose to bill nothing for very quick consultations. She said Medinet only took a platform fee from private billings.

Ms van der Rijt said the staff member had wanted to emphasise “positive news” about billing, but that they would be more explicit in future.

Patient data went straight to the doctor’s PMS via a plugin and “does not go anywhere else”, she said, but was stored for future visits to Medinet.

Chair of the RACGP board Associate Professor Charlotte Hespe said the college had long lobbied for telehealth as a “tool for improving accessibility of appropriate care at the appropriate time. But if it is just an online service, there’s an awful lot that that is missed out on.

“Our biggest concern is about how much responsibility these online services are really taking.”

She said the original restrictions had excluded too many patients, “but there’s other ways of ensuring that the practice providing the service is actually a comprehensive service”.

The Health Department said telehealth would be subject to compliance monitoring, with breaches reported to AHPRA.

Telehealth must only be offered when it was clinically appropriate and providers had to be able to show they could ensure safe and appropriate care, “including in circumstances where it becomes apparent that the patient needs face-to-face treatment during an attempted telehealth service”.

Professor Hespe said this ought to mean all telehealth providers had links with bricks-and-mortar clinics wherever patients might be.

Melbourne GP Karen Price said medicine was becoming a mercantile rather than a professional business.

“There’s a concern about a McDonald’s drive-through kind of telehealth,” she told TMR. “There are people inserting themselves into the space opportunistically.”

Another GP said general practice was being commoditised, and that those still practising face-to-face, using PPE, were bearing all the risk while the telehealth-only outfits were taking the reward.

Dr Price said practice income was down, but that wasn’t the issue for most GPs she knew, who felt lucky to be working at all.

She shared an email from a recruiter for a new medical centre offering telehealth, promising GPs a handsome $300,000 a year.

“I don’t think I’ve ever earned that in my life,” Dr Price said. “The better you do your job, the less you earn.”