A systematic approach to assessing a febrile child can help calm anxious parents

Fever is one of the most common reasons children are brought to medical attention.1,2 Parents expect a thorough examination of, and diagnosis for, a child with fever.3

We will concentrate here on acute fever and common or controversial issues and only briefly mention prolonged or recurrent fevers. We will not cover children with specific chronic diseases, such as immunosuppression. We cannot write another fever guideline here, but we will use The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines4,5 as our framework.

WHAT IS FEVER?

Fever is an elevation of body temperature that exceeds the normal daily variation.6 There is a diurnal variation in body temperature with a peak in the early evening and a nadir in the morning. Fever can be defined as a rectal temperature that is 39°C.7

Sometimes parents are worried their child may get brain damage from the fever.

Body temperature is regulated by thermosensitive neurons located in the anterior hypothalamus. Fever occurs in conjunction with an increase in the hypothalamic set point, most commonly due to pyrogens. Pyrogens are either endogenous (including interleukins and interferons) or exogenous, (mainly infectious agents), which stimulate production of endogenous pyrogens.

In contrast, hyperthermia, otherwise known as heat stroke, refers to an uncontrolled increase in temperature that exceeds the body’s ability to lose heat. Unlike fever, in hyperthermia there is no change in the hypothalamic set point and no involvement of pyrogens. For a child with fever (as opposed to hyperthermia) there is no evidence of risk of brain damage.6,8

INTERPRETING PARENTS’ REPORTS

The key question is “How was the temperature measured?” There are different recommendations from different authorities. We have therefore summarised two key references:

The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne recommends:

• Infants < three months old: axillary temperature (placed over the axillary artery for three minutes)

• Children > three months of age: tympanic temperature (retract the pinna to straighten the external auditory meatus and direct the instrument at the tympanic membrane)9

NICE recommends:

• Infants < four weeks: axillary electronic thermometer.

• Children > four weeks: options include either axillary or an infra-red tympanic thermometer.4

RCH Melbourne also recommends considering a rectal temperature in neonates if the axillary temperature is elevated;9 we would not recommend this in primary care. NICE also recommends the use of an axillary chemical dot thermometer over the age of four weeks,4 but this technique is not commonly used locally in our experience.

TEMPERATURE AND SERIOUS ILLNESS

The question for the clinician is: “Can the height of body temperature in a young child with fever be used to predict the risk of serious illness or mortality?” It is not straightforward.

NICE recommends that:

• The height of body temperature alone should not be used to identify children with serious illness.

However, these children should be recognised as being in a high-risk group for serious illness:

Children younger than three months with a temperature of 38°C or higher

Children aged three to six months with a temperature of 38°C or higher

FEVER WITHOUT A FOCUS

This can be sub-classified into:

1. “Fever without localising signs” or fever without a source (more common); and

2. “Fever of unknown origin”

PRIORITIES IN CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

1. How unwell is the child clinically?

2. Are there risk factors for a serious aetiology?

3. Is there a recognisable source?

In practice, questions one and two run together. Even if we can identify a source of fever, we must still consider both the possibility of a serious aetiology and any systemic effects of the infection. After all, viral bronchiolitis and gastroenteritis are frequent reasons for infants to present to Emergency Departments in Australia.10

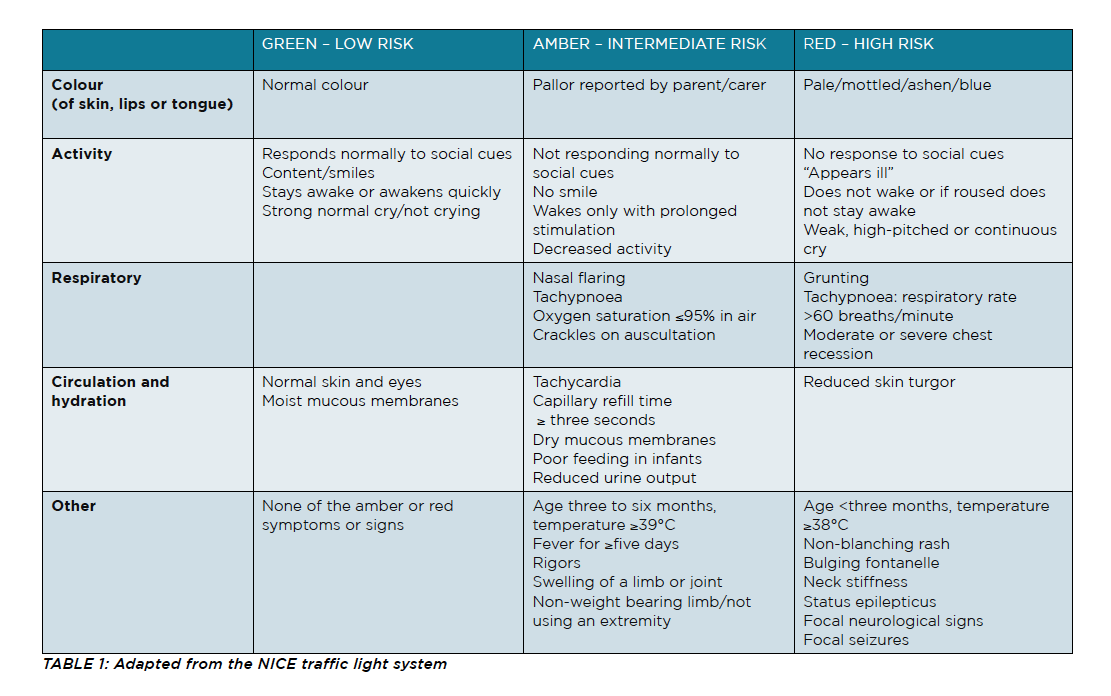

The NICE guidelines classify children into intermediate and high risk of serious illness and provide an approach for the “paediatric specialist” and for the “non-paediatric practitioner.” We recognise the significant paediatric experience of GPs in Australia and that some practitioners are based in regional and remote regions. Therefore, while concentrating on assessment in general practice, we do summarise an approach by hospital-based emergency and paediatric acute care clinicians.

RISK FACTORS FOR A SERIOUS AETIOLOGY

The NICE guidelines recommend:

Management by the “non-paediatric practitioner”

If a child has no clear diagnosis but has “amber” features, carers should receive advice on warning signs and while NICE includes a clinical review as an option, we would strongly recommend clinical follow-up. NICE also gives the option of referral to emergency paediatric services, and if there is any doubt then we would certainly support this.5

Management by the “paediatric specialist”

Infants < three months with fever should be observed and have heart rate, respiratory rate and temperature measured.

Children with fever without an apparent source with one or more “red” features should have blood and urine testing at a minimum.5

What do we think?

Overall we like this approach, but would add these points we have found useful in our experience.

1. Neonates (less than one month of age corrected) with a fever of ? 38oC all require urgent referral to hospital for investigations and empirical intravenous antibiotics.4

2. In a large Australian study in a tertiary children’s ED, the NICE traffic light system failed to identify a substantial proportion of serious bacterial infections, particularly urinary tract infections. The addition of urine analysis significantly improved test sensitivity, making the traffic light system a more useful triage tool for the detection of serious bacterial infections in young febrile children.11 We will cover UTIs in more detail below.

3. Expert opinion recommends that heart rate is potentially an important indication of serious illness, especially septic shock.4

4. Parental concern should always be taken seriously.12

For the general practitioner, this organised follow-up may include an informed discussion with the carer regarding red flags and the need to present to ED if red flags are noted before a scheduled review.

For a proportion of patients there will exist enough doubt after assessment by the practitioner as to whether the carer is capable of fully comprehending explanations or following through instructions even with written factsheets; one example of which is at https://www.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/fact-sheets/fever

For some patients there is enough doubt based on a combination of warning signs. Our recommendation is to have a low threshold to refer these children to ED after also weighing up the social impact of ED presentation on the family.

“Just monitoring” with the passage of time in the ED or a short admission for observation – both of which we regard as in fact monitoring for the development of red flags – is sometimes the safest approach. We know that most children with fever without source will have a self-limiting illness but there is no gold standard to differentiate those with a serious bacterial illness from those with “just a virus”.

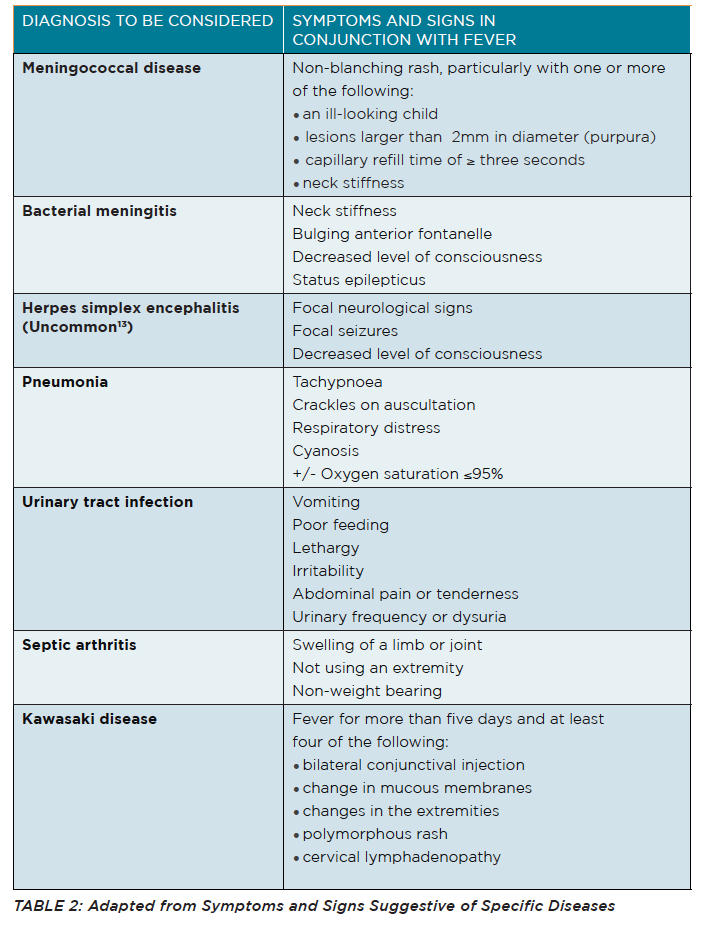

MORE SPECIFIC SERIOUS DISEASES

Apart from the features mentioned in Table 2 (See Page 28) we would add the following: a high index of suspicion is needed for Kawasaki disease, prompt referral to a paediatric facility is required with timely administration of intravenous immunoglobulin to decrease the risk of coronary artery aneurysms.14 Also absence of neck stiffness and/or a normal anterior fontanelle do not exclude bacterial meningitis in young children.15

COULD IT BE A UTI?

Table 2 will give clues, but a UTI, pneumonia and bacteraemia are probably the most common serious bacterial illnesses in young children with fever.4,11,16

Does the child need a urine sample?

NICE recommends any child with an unexplained fever of 38°C or higher should have a urine sample tested within 24 hours.17

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), in its guidelines on UTI in infants aged two to 24 months has a different approach. For an infant with fever without source who is not assessed as currently unwell enough to require IV antibiotics, the AAP recommends a stratified approach, depending on the clinician’s assessment of the pre-test probability of a UTI:

• No urine testing; or

• Obtain a urine specimen through catheterisation or suprapubic aspiration (SPA) for culture and urinalysis; or

• Dipstick testing on a urine specimen through the “most convenient means” and to perform a urinalysis or microscopy, if either is suggestive of an UTI then obtain a clean urine sample.18

Can’t I just use a bag to get the urine sample?

NICE recommends a clean catch urine sample as the recommended method for urine collection, and if this is not possible then to use urine collection pads.17 However in our experience, urine collection pads are not commonly used here. Therefore the next step would be to obtain urine by catheterisation or SPA, the latter preceded by ultrasound to demonstrate the presence of urine in the bladder.17

Perhaps not surprisingly, the AAP differs and recommends urine be obtained through catheterisation or SPA.18

Both NICE and the AAP note that contamination is a problem when collecting urine using bags.17,18 Furthermore, dipstick testing is unreliable in children under the age of two.17

Obtaining a clean catch urine sample is not easy in the ED, both due to the time taken and depending on who caught the sample – how “clean” was the catch (for example was the penis lying in the container or the container pressed up against the perineum?) and this process is clearly even more difficult in general practice.

Most infants who require a catheter or SPA urine sample will need to be referred to hospital. Our recommendation is that whatever one’s approach, a clean (at least a non-bag) urine sample is required before commencing antibiotics (which could be ceased if the culture comes back negative).

COULD IT BE TEETHING?

Studies and a meta-analysis have reported a rise in temperature for teething but not frequent or significant enough a rise to be characterised as fever.19-25 So in a nutshell, teething should not be considered the sole focus of any reported fever.

COULD IT BE CANCER?

The most common types of cancer in childhood include:

• Leukaemia

• Central nervous system tumours

• Lymphomas

• Neuroblastoma26

In children, early symptoms of childhood malignancies can be non-specific and mimic benign processes, so a high degree of suspicion is required. Fever (due to the disease process itself or febrile neutropenia) can be one of the presenting features particularly in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, which is the most common childhood cancer.26,27

The Cancer Council recommends considering malignancy in a child who has persistent, unexplained fever, apathy, easy bruising, bone pain or weight loss after exclusion of conditions such as UTI, pneumonia or bowel-related conditions (i.e. inflammatory bowel disease).26

ANTIPYRETIC THERAPY

The response, or lack thereof, to antipyretic therapy, is not helpful in predicting if a child has a bacterial illness.28,29

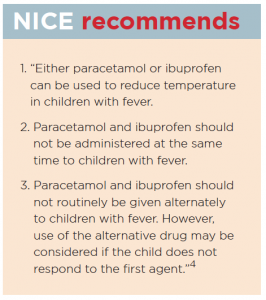

Should I advise combining or alternating paracetamol and ibuprofen – or monotherapy?

The results from a Cochrane review are hard to put into practice, but we have included a summary because fever phobia is a real issue.5,30,31

The reviewers found “moderate quality evidence” that if one combines paracetamol or ibuprofen, rather than giving either singly, this approach can:

• Result in a lower mean temperature one hour later.

• Probably result in a lower mean temperature at four hours if no further antipyretics are given.

• Result in fewer children remaining or becoming febrile for at least four hours.

This review also found that low quality evidence that alternating treatment may result in:

• A lower mean temperature at one hour after the additional dose.

• Fewer children remaining or becoming febrile for up to three hours.

There was “very low quality evidence” that combining and alternating therapies have the same effects on fever up to six hours. While there were no adverse effects reported, the report’s authors advised the need for further research on the safety of these alternating and combined regimens.32

We would recommend the NICE guidelines shown in the box above.

Does reducing fever make the child feel better (or at least, make the parent feel the child feels better)?

It has been suggested that paediatricians treat fever in children partly based on the height of the fever, but also due to the perception that this will decrease discomfort with “… improvements in activity and feeding and less irritability, and a more reliable sense of the child’s overall clinical condition.”8

Certainly defervescence may lead to an improvement in capillary refill and tachycardia, which combined with the previously mentioned benefits, could influence assessment and management. The above Cochrane review found only one study that assessed discomfort in which there was no difference between combination and alternating therapy.32

In summary, our impression is that paediatricians (and paediatric nurses) feel that reducing fever, as defined above, may improve a child’s comfort although there is scant evidence to support this.

Does treating the fever prevent my child from having a febrile seizure?

In short: No. A 2017 Cochrane review of prophylactic drugs for febrile seizures found that:

“No benefit was demonstrated for phenytoin, valproate, pyridoxine, intermittent phenobarbitone or antipyretics in the form of intermittent ibuprofen, acetaminophen or diclofenac in the management of febrile seizures.”33

HOSPITAL REFERRAL

Infants aged under three months with fever are generally at a higher risk of serious illness compared to older infants and children. These infants should all have bloods, (full blood count, blood cultures and C-reactive protein), urine testing, CXR if respiratory signs are present.

All infants younger than one month, and those aged one to three months who are assessed as unwell should have a lumbar puncture.4

PATTERN OF FEVER

To start to make a differential diagnosis one must categorise or define the pattern of fever. We like this approach from a 2005 paper (although we would use 38°C rather than 38.3°C as the cutoff). Most of these children require referral to paediatric services.

Prolonged fever

A single illness in which duration of fever exceeds that expected for the clinical diagnosis… or a single illness in which fever was an initial major symptom and subsequently is low grade or only a perceived problem.

A single illness of at least three weeks’ duration in which fever > 38.3oC is present on most days, and diagnosis is uncertain after one week of intense evaluation.

Recurrent fever

A single illness in which fever and other signs and symptoms wane and wax (sometimes in relationship to discontinuation of antimicrobial therapy),

or repeated unrelated febrile infections of the same organ system or multiple illnesses occurring at irregular intervals, involving different organ systems in which fever is one variable component.

Periodic fever

Recurring episodes of illness for which fever is the (principal) feature…associated symptoms are similar and predictable, and duration is days to weeks, with intervening (periods) of weeks to months of… (being perfectly well)34

These categories in themselves require a prolonged discussion.

differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of prolonged fevers is extensive and includes:

• Viral infections such as EBV or CMV.

• “Standard” bacterial illnesses such as a UTI.

• More exotic infections such as typhoid fever and tuberculosis.

• Malignancy.

• Autoimmune and auto-inflammatory processes such as Kawasaki disease, inflammatory bowel disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.35

Similarly the differential diagnosis of recurrent or periodic fevers is also extensive.

Our suggestion for primary care providers would be to promptly seek paediatric input for any child with:

• Fever for five days;

• Recurrent fever with any concern about a immunodeficiency (an excellent resource is available online from RCH Melbourne; (https://www.rch.org.au/kidsconnect/prereferral_guidelines/Recurrent_Infections_and_Primary_Immune_Deficiency_PID/)

• Recurrent fever with any concern about an underlying chronic disease (infectious or otherwise);

• Suspected periodic fever.

FINAL THOUGHTS

There is no gold standard for differentiating a child with a bacterial process from a viral one. Take into account the age of the child and other risk factors for a serious illness, assess how the child is systemically, consider UTI in a child with a fever without a source.

Refer children under one month of age corrected, those with red flags, or those in whom one cannot exclude a bacterial illness and follow-up will be after too long a time or adherence is questionable.

Also refer children with prolonged or periodic fever, and consider whether to refer children with recurrent fever.

Dr Stephen Sze Shing Teo is staff specialist paediatrician, Blacktown and Mount Druitt Hospitals in NSW, and senior lecturer, paediatrics, Western Sydney University

Nicola McKay is paediatric clinical nurse consultant, Blacktown and Mount Druitt Hospitals, Western Sydney Local Health District

Acknowledgements:

We thank Dr Shane Carlisle for his extremely helpful comments in the writing of this article

References:

1. de Bont EG, Peetoom KK, Moser A, Francis NA, Dinant GJ, Cals JW. Childhood fever: a qualitative study on GPs’ experiences during out-of-hours care. Family Practice 2015;32:449-55.

2. Stewart M, Werneke U, MacFaul R, Taylor-Meek J, Smith HE, Smith IJ. Medical and social factors associated with the admission and discharge of acutely ill children. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1998;79:219-24.

3. Chapron A, Brochard M, Rousseau C, et al. Parental reassurance concerning a feverish child: determinant factors in rural general practice. BMC Family Practice 2018;19:7.

4. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Feverish illness: assessment and initial management in children younger than 5 years. 2007. London. Available at: wwwniceorguk/CG047 Accessed 18 March 2019.

5. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management (NICE Clinical Guideline 160). 2013. London. Available at: https://wwwniceorguk/guidance/cg160 Accessed 5 March 2019.

6. Dinarello CA, Porat R. Fever. In: Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018.

7. Nield LS, Deepak Kamat D. Fever. Chapter 176. In: Kliegman RM, F. SB, St Geme JW, F. SN, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed: Elsevier; 2016:1277-9.e1.

8. Sullivan JE, Farrar HC. Fever and antipyretic use in children. Pediatrics 2011;127:580-7.

9. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. Febrile Child. 2018. Available at: https://wwwrchorgau/clinicalguide/guideline_index/febrile_child/ Accessed 17 March 2019.

10. Acworth J, Babl F, Borland M, et al. Patterns of presentation to the Australian and New Zealand Paediatric Emergency Research Network. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2009;21:59-66.

11. De S, Williams GJ, Hayen A, et al. Accuracy of the “traffic light” clinical decision rule for serious bacterial infections in young children with fever: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2013;346:f866.

12. Burkes M, Goodman A. Tips for GP trainees working in paediatrics. The British journal of general practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 2011;61:68-9.

13. Le Doare K, Menson E, Patel D, Lim M, Lyall H, Herberg J. Fifteen minute consultation: Managing neonatal and childhood herpes encephalitis. Archives of Disease in Childhood – Education & Pactice Edition 2015;100:58-63.

14. Golshevsky D, Cheung M, Burgner D. Kawasaki disease–the importance of prompt recognition and early referral. Australian Family Physician 2013;42:473-6.

15. Tacon CL, Flower O. Diagnosis and management of bacterial meningitis in the paediatric population: a review. Emergency Medicine International 2012;2012:320309.

16. Craig JC, Williams GJ, Jones M, et al. The accuracy of clinical symptoms and signs for the diagnosis of serious bacterial infection in young febrile children: prospective cohort study of 15 781 febrile illnesses. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2010;340:c1594.

17. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Urinary tract infection in under 16s: diagnosis and management. 2007. London.Available at: https://wwwniceorguk/guidance/cg54 Accessed 9 March 2019.

18. Roberts KB. Urinary tract infection: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics 2011;128:595-610.

19. Cunha RF, Pugliesi DM, Garcia LD, Murata SS. Systemic and local teething disturbances: prevalence in a clinic for infants. Journal of Dentistry for Children (Chicago, Ill) 2004;71:24-6.

20. Jaber L, Cohen IJ, Mor A. Fever associated with teething. Arch Dis Child 1992;67:233-4.

21. Macknin ML, Piedmonte M, Jacobs J, Skibinski C. Symptoms associated with infant teething: a prospective study. Pediatrics 2000;105:747-52.

22. Massignan C, Cardoso M, Porporatti AL, et al. Signs and Symptoms of Primary Tooth Eruption: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20153501.

23. Memarpour M, Soltanimehr E, Eskandarian T. Signs and symptoms associated with primary tooth eruption: a clinical trial of nonpharmacological remedies. BMC Oral Health 2015;15:88.

24. Tighe M, Roe MFE. Does a teething child need serious illness excluding? Archives of Disease in Childhood 2007;92:266-8.

25. Wake M, Hesketh K, Lucas J. Teething and tooth eruption in infants: A cohort study. Pediatrics 2000;106:1374-9.

26. Cancer Council. Red Flags – Warning signs of cancer in children. Available at: https://wwwcancerorgau/health-professionals/primary-care-resources/red-flags-warning-signs-of-cancer-in-childrenhtml Last updated 5 April 2018 Accessed 18 March 2019.

27. Redaelli A, Laskin BL, Stephens JM, Botteman MF, Pashos CL. A systematic literature review of the clinical and epidemiological burden of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). European Journal of Cancer Care 2005;14:53-62.

28. Baker MD, Fosarelli PD, Carpenter RO. Childhood fever: correlation of diagnosis with temperature response to acetaminophen. Pediatrics 1987;80:315-8.

29. Weisse ME, Miller G, Brien JH. Fever response to acetaminophen in viral vs. bacterial infections. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 1987;6:1091-4.

30. Bertille N, Purssell E, Corrard F, Chiappini E, Chalumeau M. Fever phobia 35 years later: did we fail? Acta Paediatrica 2016;105:9-10.

31. Sahm LJ, Kelly M, McCarthy S, O’Sullivan R, Shiely F, Rømsing J. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of parents regarding fever in children: a Danish interview study. Acta Paediatrica 2016;105:69-73.

32. Wong T, Stang AS, Ganshorn H, et al. Combined and alternating paracetamol and ibuprofen therapy for febrile children. The Cochrane Database of systematic reviews 2013:Cd009572.

33. Offringa M, Newton R, Cozijnsen MA, Nevitt SJ. Prophylactic drug management for febrile seizures in children. The Cochrane Database of systematic reviews 2017;2:Cd003031.

34. Long SS. Distinguishing among prolonged, recurrent, and periodic fever syndromes: approach of a pediatric infectious diseases subspecialist. Pediatric Clinics of North America 2005;52:811-35, vii.

35. Ishimine P. Assessment of fever in children. BMJ Best Practice 2018.